The prehistoric practice of using controlled fires to produce customised stone tools dates back 300,000 years, according to new research. The discovery affirms the cognitive and cultural sophistication of human species living at this time.

The baked flint tools, found at Qesem Cave in central Israel, are evidence that early hominins were capable of controlling the temperature of their fires and that they had stumbled upon an important survival skill, according to new research published today in Nature Human Behaviour.

The heating of flint at low temperatures allowed for better control of flaking during knapping. Armed with this level of control, tool builders could cater their tools for specific cutting applications. The new paper was led by archaeologist Filipe Natalio from the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel.

Silje Evjenth Bentsen, an anthropologist at the University of Bergen who wasn’t involved in the new study, said fire use among hominins is currently a hot topic in archaeological research, and for good reason.

“I personally think that hominins could not survive long in the cold climate of Eurasia without hot food and a warm fire, but some researchers still argue that controlled and habitual use of fire came quite late,” explained Bentsen in an email. “If hominins in Qesem Cave were using fire 300,000 years ago as a technology and as part of their tool production strategies, it is a sign of advanced use of fire. And as such, it could also help us understand how and when hominins controlled fire and used it casually in their everyday life.”

Our species, Homo sapiens, had only recently emerged in Africa during this period, so it’s unlikely they were responsible for these stone tools. At the same time, several hominin teeth found in Qesem Cave bear a resemblance to those of Neanderthals, so they’re a likely candidate. Regardless, both Homo sapiens and Neanderthals “undoubtedly possessed the required cognitive abilities to implement the heat-treatment described in the new paper,” according to Katja Douze, an anthropologist at the University of Geneva who isn’t affiliated with the new research.

This tool-making technique is known to archaeologists. Previous research suggests the practice was being employed in the Levant between 420,000 and 200,000 years ago. Bits of burnt flint hinted at the practice, but it was unclear if this was just a random thing or if the people were actually in control of their fires for the purpose of crafting stone tools.

Douze said the practice of using fire to produce wooden spears dates back some 400,000 years, but “heat-treatment of stone probably required a higher technical effort, especially for flint that is very sensitive to abrupt temperature changes,” she said. If the heating process isn’t well mastered, “the rock breaks immediately and is no longer usable,” she said. Accordingly, the new paper shows that, “not only is this mastery very old, it’s also complex.”

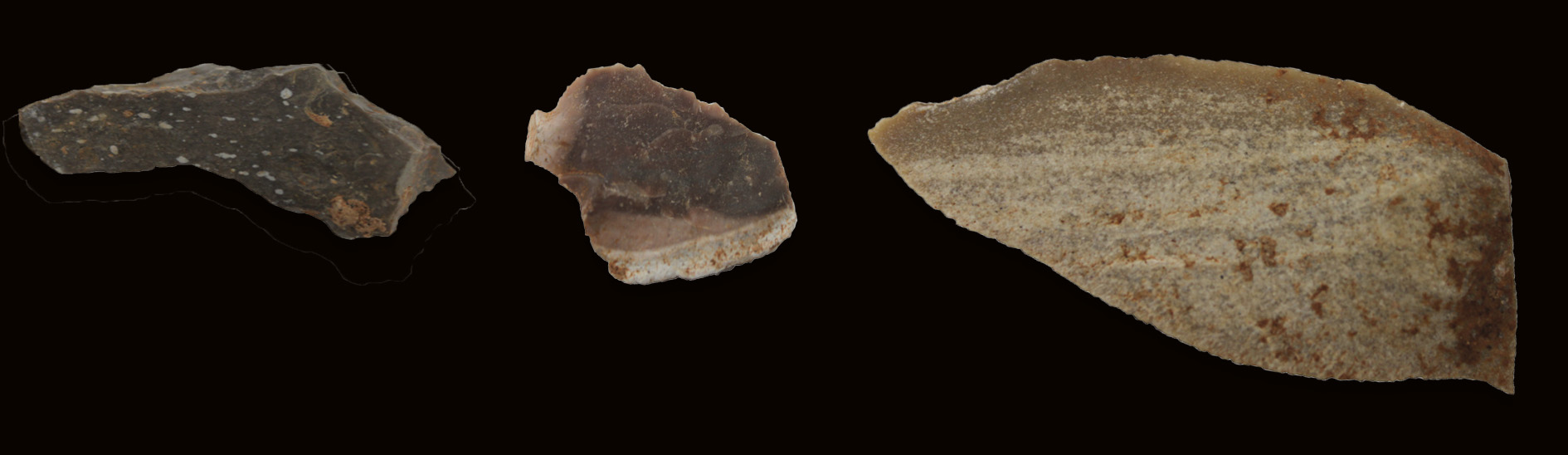

As evidence of this heat-treatment, Natalio and his colleagues analysed two types of flint tools found in Qesem Cave, which is known to have hosted fires in its ancient past. They used a spectroscopic chemical analysis and machine learning to estimate the temperature at which the flint items were heated. Results showed that the blades were heated to 259 degrees Celsius, which is lower than the flakes, which got as hot as 413 degrees Celsius. Pot lids found at the same site got even hotter, with temperatures reaching 447 degrees Celsius.

For Douze, the demonstration of different heating temperatures for the blades and flakes was the high point of the study.

“This difference also ensures that there is absolutely no doubt about the deliberate heating of stone on this site,” said Douze. “Now, it remains to be determined how these hominins proceeded to heat their blocks on site and how they managed the different heating temperatures.”

Possibilities cited by Douze include the use of sand baths beneath the fireplaces in which they placed their blocks, or possibly multiple types of heating systems required to achieve each of the required temperatures.

“The use of machine learning is an innovative method and provides new possibilities for future studies,” said Bentsen. “The flint samples were heated in a controlled environment in an oven in a laboratory. This gives us a good baseline for all the heat-induced changes in the flint.”

Smartly, the authors also performed some experimental archaeology, in which they replicated these conditions to test the plausibility of the computer’s estimates. It worked, as the authors explained in their study:

These preliminary knapping experiments seem to support the idea that controlled heating of flint at relatively low temperatures offers a higher degree of control over flakability, and improved blade production, rendering them more suitable for specific activities (for example, higher efficiency in butchering game).

This prehistoric technique, however, came at a cost, as it would’ve required the hominins to steadily collect fuel for the fire — a high-energy activity. Consequently, the authors hypothesise that fuel collection was done to support stone tool production as well as day-to-day activities, such as cooking.

That these ancient hominins were capable of this task is a big deal, as Bentsen explained.

“The ability to plan ahead and understand the many different steps of a process is a vital survival skill,” she said. “This process requires many steps and careful planning; you need to know which rocks to heat, and gather all the rocks and the fuel. You must create enough heat — not too hot, not too cold — and understand how long the fire must be going. And after heating, the rocks must be allowed to carefully cool down before being used or worked on.”

To which Bentsen added: “The study by the Qesem team suggests that early hominins mastered this process 300,000 years ago or even earlier, and that gives us much food for thought.”