As the Jedi master Qui-Gon Jinn once said, “There’s always a bigger fish.” Or in the case of the Triassic Period, there’s always a bigger aquatic reptile, as this incredible fossil demonstrates.

New research published in iScience offers the oldest direct evidence of “megapredation” in the fossil record, in which an apex predator feeds upon formidably sized prey.

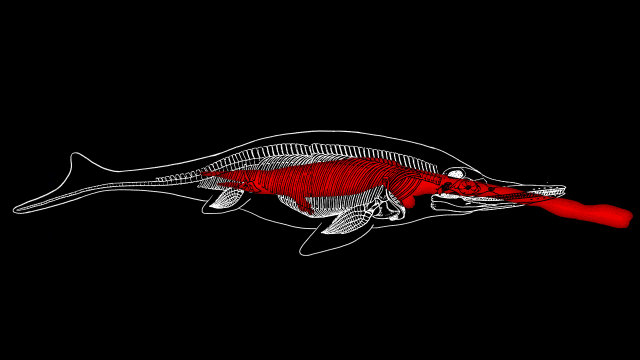

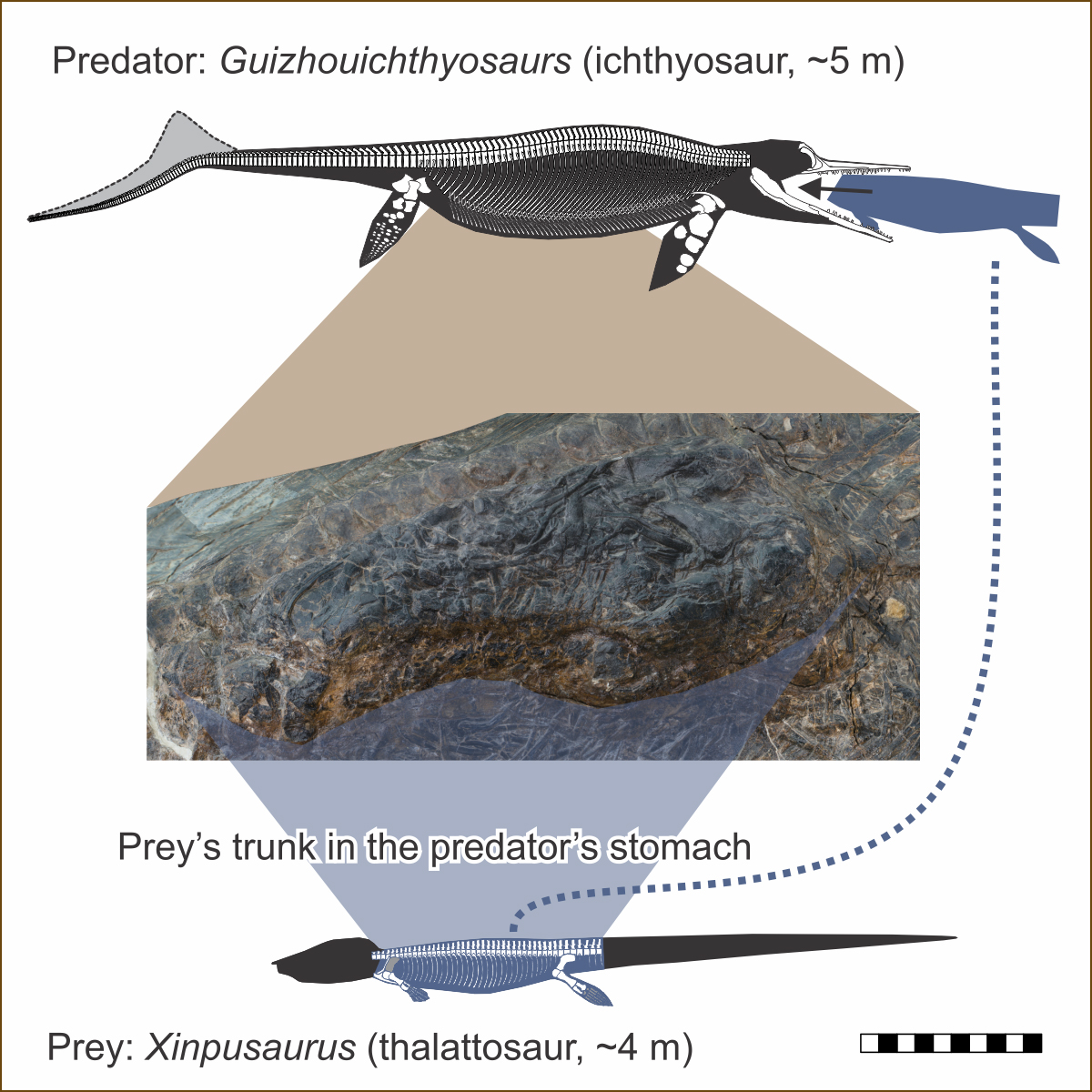

The fossil, found at a quarry in Guizhou province of southwestern China, appears to show a 4.57 m-long ichthyosaur (pronounced “ick-thee-oh-sore”) shortly after feasting upon a 3.66 m-long thalattosaur. Regrettably, the ichthyosaur probably died shortly after its meal, having bitten off more than it could handle.

Ichthyosaurs were dolphin-like aquatic reptiles that emerged during the Triassic. This particular specimen belonged to an ichthyosaur species known as Guizhouichthyosaurus tangae, which grew as long as 10 metres. Its presumed prey, a thalattosaur species called Xinpusaurus xingyiensis, was more lizard-like, with four limbs that it used to paddle through the water. The new fossil is the first direct evidence to suggest at least some species of ichthyosaurs were apex predators, similar to orcas today.

The nearly complete fossil, dated at 240 million years old, suggests the ichthyosaur swallowed an animal not that much smaller than itself, in what proved to be a fatal decision. Prior to this discovery, scientists had “never found articulated remains of a large reptile in the stomach of gigantic predators from the age of dinosaurs, such as marine reptiles and dinosaurs,” explained Ryosuke Motani, a co-author of the study and a paleontologist from the University of California, Davis, in a UCD press release. Prior to this discovery, scientists thought that ichthyosaurs fed exclusively on fish and cephalopods.

“Finding any animal other than fish or squid in an ichthyosaur’s stomach contents is incredibly rare — and in fact, finding fish or squid in an ichthyosaur’s stomach is also quite rare,” Dean Lomax, a paleontologist at the University of Manchester who wasn’t involved in the new research, said in an email. “Only a handful of other different types of animal have been found inside an ichthyosaur’s stomach as food, so the discovery of a fairly large ichthyosaur with a comparatively very large thalattosaur dinner is highly unusual.”

Lomax knows a thing or two about fossils embedded inside of fossils. Back in 2018, he co-authored a research paper describing a pregnant ichthyosaur fossil with several unborn young still packed within its ribs.

“One of the most significant things about specimens like this is that they provide absolutely unique and direct information about the behaviour of long-extinct species,” said Lomax. “It is easy to presume that X fed on Y, but when you have evidence like this, there is no longer any guess work.”

It’s not clear if the new fossil is an example of predation or scavenging, the authors admit. Scavenging doesn’t seem likely, however, given the evidence; limbs tend to fall off decomposing bodies prior to the tail falling off. In this specimen, the opposite is seen: the thalattosaur’s limbs are still attached to its body, but the tail is missing. Astonishingly, paleontologists found this creature’s fossilised dismembered tail just a few feet away, which could’ve been lost during its fateful encounter with the ichthyosaur, according to the authors. Regardless, the new evidence suggests this species of ichthyosaur, whether hunter or scavenger, consumed large meals, which wasn’t known before.

That the tail was found nearby seemed almost too good to be true, so we asked Lomax what he thought.

“Your point about the tail raised my curiosity as well, although it appears genuine,” he said. “It caught my interest, however, because the authors remark that the ‘predator likely died soon after ingesting the prey.’ This they allude to by assuming that an isolated tail of a thalattosaur was from the same individual consumed by the ichthyosaur. If this is correct, then it might suggest that the predator had bitten off more than it could chew, in that it was a much larger meal than it had anticipated and which could have led to its downfall.”

It’s hard to know exactly why the ichthyosaur died, but assuming this interpretation is correct — that the isolated tail belongs to the same thalattosaur — then the ichthyosaur’s death could be linked to its hefty meal, explained Lomax.

Another possibility is that the two sea creatures died atop each other, and the fossils are merely juxtaposed. And indeed, the thalattosaur fossil does not show signs of having been degraded by stomach acid, but, to be fair, that observation also makes sense when considering the favoured hypothesis: that the ichthyosaur died soon after swallowing the thalattosaur.

The discovery is shedding new light on the dietary habits of ichthyosaurs, which were presumed to feast entirely on cephalopods owing to their small, peg-like teeth. The new evidence suggests otherwise — that these teeth were used to grip prey, shatter spines, and rip apart flesh.

“Now, we can seriously consider that they were eating big animals, even when they had grasping teeth,” explained Motani in a Cell Press press release. “It’s been suggested before that maybe a cutting edge was not crucial, and our discovery really supports that. It’s pretty clear that this animal could process this large food item using blunt teeth.”

[referenced id=”1222514″ url=”https://gizmodo.com.au/2020/06/8-wild-examples-of-evolution-copying-itself/” thumb=”https://gizmodo.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/12/bm0ioas5jvqxkopwn0d0-300×169.png” title=”8 Wild Examples of Evolution Copying Itself” excerpt=”Every once in a while, Darwinian natural selection stumbles upon the same solution more than once, in a process known as convergent evolution. Here are our favourite examples of evolution making the same creature, or same physical trait, twice.”]

Modern apex predators such as orcas and leopard seals apply similar predatory tactics, in what is a possible example of convergent evolution. And indeed, the ichthyosaur itself is the poster child for convergent evolution, where unrelated species evolve similar physical characteristics. Ichthyosaurs are typically compared to dolphins, but as the new research shows, a more accurate comparison might be to killer whales.