Right now, Big Freedia is at the top of her career. In the past five years, the bounce music artist has been sampled on Beyoncé’s banger, “Formation” (she’s the one saying, “I came to slay, bitch”), and Drake’s “Nice for What” (aka the song of summer 2018). But 15 years ago, she was holed up in a duplex with several family members, waiting for a hurricane to pass.

“I really went through it during Katrina,” she said, shaking her head.

In the days before Hurricane Katrina, the government issued warnings. But storms were a regular occurrence in the region, and Freedia and her family figured it would be no big deal.

Katrina ended up being one of the worst climate disasters of the century. The winds knocked an oak tree into Freedia’s family’s home, destroying the roof. When the city’s levees broke, they fled their home, looking to catch a bus to head to the now-infamous Superdome emergency shelter. But the buses never came, and Freedia and her relatives ended up spending the next couple of nights sleeping on a bridge.

Thousands of New Orleans residents have stories like these. Some were forced to wait on their roofs or in their attics for days before help arrived, if it ever did. Katrina killed more than 1,800 people, and destroyed or damaged 800,000 homes and altered the course of a city forever.

When Freedia was finally able to evacuate days after the storm pounded the city, it still wasn’t easy.

“I had to go on a big old cargo plane to Arkansas and sleep at an army base, and then at a campground,” she said.

Eventually, like some 250,000 other evacuees, she ended up in Houston. There, she started getting booked to play shows, and people loved her.

“My name was ringing,” she said. “People started saying, ‘what kind of music is that?’”

Like jazz and blues before it, New Orleans’ quintessential style of hip hop is full of stories of joy and suffering, oppression and liberation. Katrina changed everything in the city, including the music. But as locals struggled to find hope after a disastrous storm, bounce helped them find it as well as community.

Big Freedia is known for popularising bounce music, a New Orleans style of hip hop built on simple, one-bar drum beats, call-and-response style refrains, outrageously sexual lyrics, and perhaps most importantly, beats you can shake your arse to. The bounce scene is where the word “twerk” originated, and it’s easy to hear why when a bounce beat drops.

Bounce first sprung up from housing projects, nightclubs, and block parties in the late 1980s and early 1990s from artists like MC T. Tucker, Leroy “Precise” Edwards, DJ Jubilee, and Mia X. But Freedia was at the forefront of a new wave of bounce led by queer artists that was emerging in New Orleans in the mid-aughts when Katrina struck the city. It was this genre, Freedia said, that helped her find resilience in the wake of disaster.

“I was hustling so hard, you know? Trying to make ends meet, trying to get my life back in order,” she said. “And bounce music was an outlet to keep me focused, and to keep me making people happy and bringing people joy.”

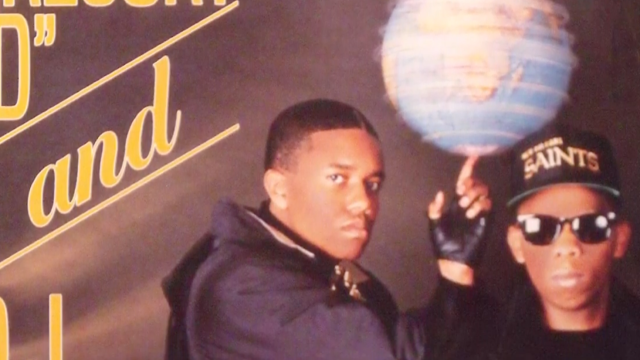

Though it’s now featured in Top 40 hits, bounce began as a distinctly local genre, even featuring roll calls of housing projects and wards from around the city. In the 1989 song “Buck Jump Time” by Mannie Fresh and Gregory D, the musicians call out a string of places New Orleanians knew:

“Uptown, Third Ward, that Calliope, Melpomene, Magnolia, the home of dope. St. Thomas, Lafitte, the Iberville’s hard, and that Seventh Ward St. Bernard.”

“Bounce really was the music of…the working class and underclass of New Orleans,” said Holly Hobbs, a cultural researcher who studies bounce and founded the NOLA Hip-Hop and Bounce Archive.

When Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans in 2005, it was the city’s working class and underclass that was hit hardest. While thousands of wealthier residents of the whiter neighbourhoods drove out of the city and checked into hotel rooms, many residents of the majority poor and working class Black neighbourhoods didn’t have those options and were forced to rely on government assistance to survive.

The state and federal government thoroughly mangled that assistance. Thousands of people were forced to spend days in emergency shelters like the infamous Superdome without food or water. Rather than pouring resources into these basic needs, federal officials sent private security firms strapped with guns to guard Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) employees, who terrorised Black residents. Two months after the storm, FEMA director Michael Brown was forced to resign after he acknowledged that the government knew the city’s flood barriers protecting New Orleans were inadequate, yet failed to upgrade them.

Bounce artists chronicled all of this mismanagement on the mic. In a song called “Fuck Katrina,” the late artist Fifth Ward Weebie seethed about the inadequacies of the assistance the government provided, as did Mia X in a song called “My FEMA People.”

“All through the city, we were left for dead, for vultures,” she raps. “It’s so much bigger than the weather.”

In the wake of the storm, some 400,000 New Orleans residents were forced to relocate, leaving their city behind. But they brought bounce music with them. That spread the style to new places and kept those displaced connected to the homes they left behind in the wake of the storm.

“Wherever I heard bounce music at, if you were from New Orleans, I didn’t even have to know you,” said artist Hasan “HaSizzle” Matthews, who was forced to relocate from New Orleans’ Calliope projects to Dallas after the storm. “I came over to you and I was like, ‘I’m from New Orleans, too.’”

Like Big Freedia, HaSizzle found a new audience for his music in Texas, as did other bounce artists, like Mia X and DJ Chicken, who began hosting bounce nights at Dallas clubs. As bounce grew in popularity across the South, it also began to find new audiences in New Orleans itself, as a new wave of people moved to the city.

A year after being displaced by the deluge, Big Freedia moved back to New Orleans, where she was determined to rebuild the bounce scene. She began hosting a weekly night called “FEMA Fridays” at Caesar’s, a club in the city’s West Bank.

“It was the only club that was open in New Orleans at the time, so the lines were down the street and the people were all around the corner,” she said. “They had FEMA money and Red Cross money and they were popping bottles, and shaking arse. It was just an amazing feeling.”

Hobbs said queer artists like Freedia were among the first bounce musicians to come back to the city after the storm. She also noted that demographics in the city started to shift after the storm.

That was driven in part by what city officials did to majority Black neighbourhoods. They demolished entire blocks, including some of the housing projects shouted out in bounce tracks like the Magnolia and the Calliope. Some residents weren’t even able to come back and retrieve their belongings.

“It changed everything,” Freedia said. “It definitely changed the people that was in certain neighbourhoods. They started to gentrify the neighbourhoods and they redid the buildings and the structures and the streets.”

Due to inequalities in the city’s rebuilding plans and uneven distribution of resources, white New Orleans residents were able to return to their homes much faster on average than Black residents. At the same time, a new population of young, white people from the coasts began to move into the city, too.

Before the storm, some bounce songs, like New Orleans’ legend Juvenile’s 1999 “Back That Azz Up,” broke out to a national audience. But within New Orleans, the scene was fairly insular.

“Before Katrina, bounce was hard for a person who wasn’t from New Orleans and who wasn’t already involved in the scene to find bounce. It wasn’t like there were bulletin boards and posters everywhere for bounce parties,” said Hobbs. “After Katrina, it became much more accessible. It slowly became more accessible to all walks of life, and you started to have a lot more kinds of people at these shows.”

With all of this newfound attention, bounce began to slowly enter the mainstream. First, it was through megastars from New Orleans like Lil Wayne, but eventually other pop artists started to take inspiration from bounce as well. In 2016, HaSizzle got an email from a music representative, asking if a major artist could use a quote from his song, “She Rode That Dick Like A Soldier.”

“It was Drake,” he said. “Drake!”

The quote ended up on “Childs Play” on 2016’s Views. Two years later, Drake asked Big Freedia to feature on “Nice for What.”

“My manager called me and said, I got something big for you on the table,” said Freedia. “And he was like, you wanna do a song with Drake? I’m like, fuck! You’re damn right I do!”

In the past few years, bounce sounds and artists have also been featured on songs by City Girls and Cardi B, N.E.R.D. and Rihanna, and Chris Brown and Nicki Minaj.

This mainstream attention has propelled some musicians’ to greater fame, and many of them have shared their success with people in their hometown. But the communities that created New Orleans bounce have largely not seen the benefits of the genre’s mainstreaming. Fifteen years after Katrina, many of the neighbourhoods that the genre emerged from are still struggling to rebuild.

“That’s what we see over time at pretty much any genre that’s created by a working class and permanent underclass,” said Hobbs. “Blues artists didn’t get any money from blues, or very few of them did. It wasn’t until later that people figured out, oh, this music is important and these artists should be preserved.”

HaSizzle has enjoyed new attention due to bounce entering the mainstream, but he says the genre is also being watered down.

“The only thing that they took from the music was the word ‘twerk,’” he said.

Still, he said, the genre helped Black New Orleans natives find hope after Katrina.

“New Orleans is an amazing city,” he said. “It was broken, but bounce music, I feel like it brought us all back together.”

And though the music has spread far and changed dramatically since then, it still belongs to the city that created it. Sitting on his couch in New Orleans, just miles from where he grew up, HaSizzle gestured to his window.

“If I put bounce music on right now, the streets out there would all start to fill up,” he said.

The Root’s Felice León contributed reporting to this story.