In early August, Belarus — known as Europe’s last dictatorship — went almost entirely offline for 72 hours. On Wednesday August 26, for approximately one hour, Belarus shut down key parts of the capital’s internet once again; allegedly, the order had come directly from official state bodies.

The earlier outage disrupted communication across the protesting nation, but a slow trickle of footage, largely via minor Telegram channel NEXTA Live, broadcasted riot police attacking peaceful protesters and deploying rubber bullets and stun grenades; phone videos shot from balconies revealed guards violently beating detainees in prison yards.

As the country gradually came back online, depictions of protesters’ dark red-blue bruising, as well as claims of sadistic torture, rape threats, and sexual assault began circulating on social networks and news sites. In the centre of the conflict, the encrypted app Telegram aided by a wide range of proxies and virtual private network usage became pivotal in both disseminating information and protest organisation.

With the internet outages in Belarus, we see just what can happen when an over-dependence on centralised internet and a select few major companies meets national censorship, and what — if anything — can be done about it.

As the world watches

“When they turned off the internet… we didn’t know what was happening,” said one protester, Alena, over Facebook messenger. “I shook with indignation when information about the violence began [to spread] — the beatings, assaults, insults, shootings… All of this has now flooded the internet… We are all in collective shock.”

“When the internet was back, it was interesting — horror and pride at the same time,” another protester, Kirila (a pseudonym), said of the unprecedented images and discussions of police brutality via Reddit messenger. (The protesters are identified here by first name and pseudonym only, to protect their identities.)

The wave of protests in Belarus first began after its 65-year-old leader Alexander Lukashenko, who has presided over the nation since 1994, claimed to have won an 80 per cent victory in elections on August 9. This was widely contested by protesters and foreign observers. Opposition candidate Svetlana Tikhanouskaya claimed the victory, but later left the country for neighbouring Lithuania, apparently under duress. Multiple outlets reported thousands of protesters detained, at least one person killed, and dozens injured in the clashes; the reporting was supported by a mass of citizen documentation from the former Soviet nation. For 72 hours, attempts were made to censor the outpour.

“Starting on August 9… somewhere around 9:00 am, the internet started to be shut down,” recalled Maksimas Milta, Head of Communication and Development Unit at the Belorussian European Humanities University, the university now exiled and based in Lithuania. Milta was on the ground in Minsk when the first websites were attacked: an independent platform for tracking voting, Golos, and a crowdsourcing platform which allows users to report incidences of electoral fraud, Zubr.

“Two hours later, basically YouTube access was blocked, in order for people not to be able to watch streams, then the entire internet started to be shut down,” said Milta. Google, Facebook, and WhatsApp all suffered access issues, as well as independent news sources. Belarusian telecom providers issued apologies for mass outages, and ultimately, the end-to-end encrypted messaging app Telegram was one of the only services left.

“We enabled our anti-censorship tools in Belarus so that Telegram remained available for most users there. However, the connection is still very unstable as internet is at times shut off completely in the country,” Telegram founder Pavel Durov wrote on Twitter on August 10.

The NEXTA Live Telegram channel, run by 22-year-old Stepan Putilo based in Poland, saw its user base explode in a matter of days. At the beginning of the protests, only a few hundred thousand people knew of its existence. Now, it has more than two million subscribers.

NEXTA poses enough of an apparent threat to the authorities that according to its young founder, Putilo is “wanted” in both Belarus and Russia and facing up to 15 years imprisonment, he told the German outlet Tagesschau. Putilo will not publicly reveal his location in Warsaw, citing threats and hate messages. “My family, my mother and my brother were still in Belarus during the presidential elections, but then they received a hint from officials that it could be uncomfortable for them in Belarus,” Putilo said in the interview. “They are now in Poland too.”

As protest organisations continue to depend on these previously niche platforms, the country is also seeing a spike in VPN usage. Around August 9, Google Play Store in Belarus listed Psiphon, X-VPN, Tachyon VPN, and VPN Proxy Master in its top four app downloads, with others in the country saying they paid for Surfshark or used Shadowsocks, most well-known for circumventing the great firewall in China.

“Psiphon saw a peak of 1.759 million unique users from Belarus on August 11. We have seen extensive, sustained use starting August 9,” said Psiphon’s Michael Hull. “Psiphon use increased due to word of mouth, not marketing… word of mouth is extremely powerful,” he added.

Access to these VPNs is being facilitated by lone actors at a grassroots level. “You would see people in the elevator just leaving USB sticks with VPN access files. It’s funny, this is like low tech in action,” said Milta. “Some didn’t know about VPN, so there were a few people offline for three days,” added Kirila. “I even had the idea to spread lists with instructions on VPNs, but on the same night I came up with that idea, the internet was back.”

Denials of service

“At the orders of official state bodies, from 20:40 on August 26 in Minsk mobile internet bandwidth will be restricted. [Our] compliance with this requirement will lead to a decline in the quality of data transmission or temporary service failures,” mobile network provider A1 tweeted Wednesday.

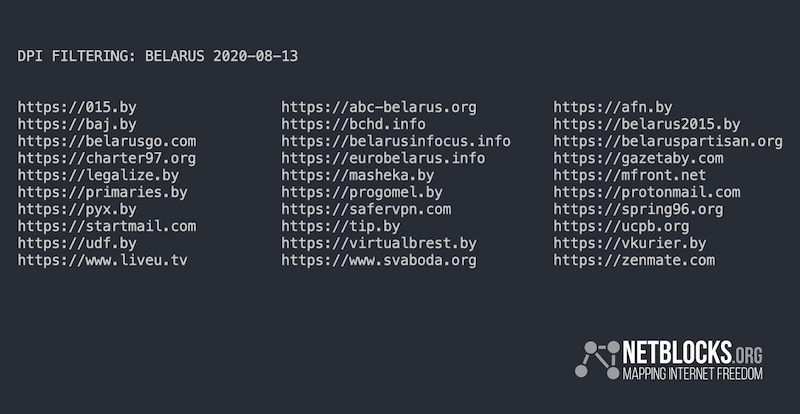

While there were different types of network challenges across August, the government attempted to play off earlier issues. Lukashenko, for his part, originally blamed “foreign cyberattacks” for the internet outages, while the National Computer Incident Response Centre of Belarus alleged DDoS attacks on government infrastructure. However, Belarus’ internet went down via a method called Deep Packet Inspection. DPI attacks were based around actual domain names, so Telegram bypassed them, benefitting from using IP addresses instead of domains.

DPI is more commonly known as “packet sniffing” outside cyber security circles and is used for watching where packets go, which is useful for monitoring traffic on sensitive networks, but is often also used for censorship. DPI was also used in Iran, according to NetBlocks, which tracks online disruptions and shutdowns. It appeared that the government employed listed keywords that it could use to block access to specific URLs. “DPI is used for filtering domain name[s] — it can filter protocol sites but that can be worked around,” said Alp Toker, NetBlocks CEO.

“Two primary mechanisms at play here when it comes to the restrictions — the link layer/network layer disruptions — the chunk of the internet route being disrupted at different times, and the DPI,” he added. Telegram was able to work because it doesn’t use domain names at all — they use IP addresses directly. “They’re quite good at leaping from address to address, so if one network goes down they switch over either automatically or just by having users enter a new setting to connect to another server,” said Toker.

The tech-heavy Belarusian economy took a severe hit as a result of the outages, reportedly losing as much as $US56 ($77) million each day. More than 2,000 investors, executives, and tech sector workers signed an open letter saying conditions in the country meant their businesses could not function. “Startups are not born in an atmosphere of fear and violence. Startups are born in an atmosphere of freedom and openness,” they stated, anticipating a slowdown in growth and even a mass exodus.

Lingering internet problems remained on August 23, with several independent news websites apparently permanently unavailable for users in Belarus. On that day, two weeks after the internet shutdown, hundreds of thousands fearlessly took to the streets once again chanting “Resign!” at Lukashenko, bearing the colours of the pre-Soviet white-and-red Belarusian flag. In the evening, cellular network MTS fell offline across Minsk as protesters approached the presidential palace, NetBlocks noted: “Operator A1 subsequently declared service quality had been reduced at the request of government agencies to ‘ensure national security.’” The issues lasted for around three hours.

The NEXTA Telegram channel once again played a pivotal role on Sunday. “Police set up checkpoints at all entrances to Minsk. Belarus looks more and more like a war zone,” NEXTA wrote. The channel was responsible for spreading directions to participants, from basic practicalities such as “take water” and “tomorrow it might be rainy, so don’t forget raincoats or umbrellas” to helping people organise outside the capital, Minsk, and suggesting tips for how to deal with being stopped by traffic police.

The past weekend’s protesters wielded images depicting the previous weeks’ police brutality. “Many people brought photos of injured people during the clashes,” wrote Franak Viačorka, an Atlantic Council fellow based in Minsk. These photos, originally censored during the internet blackout, were now everywhere.

The tech giants in the shadows

While Twitter condemned the internet outages in Belarus, stating that “Internet shutdowns are hugely harmful. They fundamentally violate basic human rights & the principles of the #OpenInternet,” it would not provide further information when contacted. WhatsApp/Facebook said that it did not wish to speak on the record regarding the company’s broader responsibility to intervene in situations of potential authoritarian oppression. Google was unresponsive to requests for comment.

Smaller companies are increasingly filling the gaps left by the tech behemoths — not just in Belarus but on an international level, said Jillian C. York, Director of International Freedom of Expression at the Electronic Frontier Foundation. “I think we’ll see a lot more movement towards smaller platforms and safer platforms for organising but less so for getting the word out,” York said, suggesting people retained stronger links to their existing networks on Facebook. On a global scale the bigger social networks such as Facebook appear to have a bias towards “governments in general over the people.”

Smaller companies can provide a variety of services in nations where people experience some level of totalitarian control and can better facilitate anonymous coordination of oppressed citizens. Broadcasts via private channels while circumventing state-imposed restrictions or technological privacy issues can be pivotal to resistance .

In turn, Russia has attempted to prohibit Telegram itself in the past. It lifted its nearly two-year (and wildly ineffectual) ban in June. Telegram has said that it refused to share its encryption keys with Roskomnadzor (RKN) — the country’s communications watchdog. Twitter and Facebook also suffered fines of 4 million rubles (around $US63,000 ($87,098)) in Russia in February for refusing to store user data on servers inside the country.

Of course, platforms like Telegram come with their own issues, even as it hosts Belarusian youth coordinating protest efforts. End-to-end encryption is reserved for “secret” chats and doesn’t apply to group messages. Its server code is closed source (only its client side is open-source) which has raised some security suspicions; other messaging apps make their server code open-source too. It is also susceptible to misinformation and disinformation from its users like any other social network, as well as potential serious security flaws. Telegram is just one alternative, and hardly a minor player. But substituting the apps and services traditionally used in the US with smaller, less governed technology would allow independent channels to organise and distribute information more effectively. This may be a step in the right direction in protecting truth and transparency in the face of any potential crackdowns or internet censorship.

As of this writing, the protests in Minsk are being dispersed, with some protesters blockaded in a church. Lukashenko, reportedly, is attempting to subdue the protests “gradually.” NEXTA continues to update and organise its 2 million members. Internet connectivity in Belarus remains spotty at best.

Aliide Naylor is the author of The Shadow in the East: Vladimir Putin and the New Baltic Front (I.B. Tauris, 2020).