The unfolding crisis in California is like nothing the state has ever seen. An area the size of Rhode Island has burned in the span of a week as massive wildfires engulf the state months ahead of peak fire season, with lightning set to ignite even more blazes on Sunday.

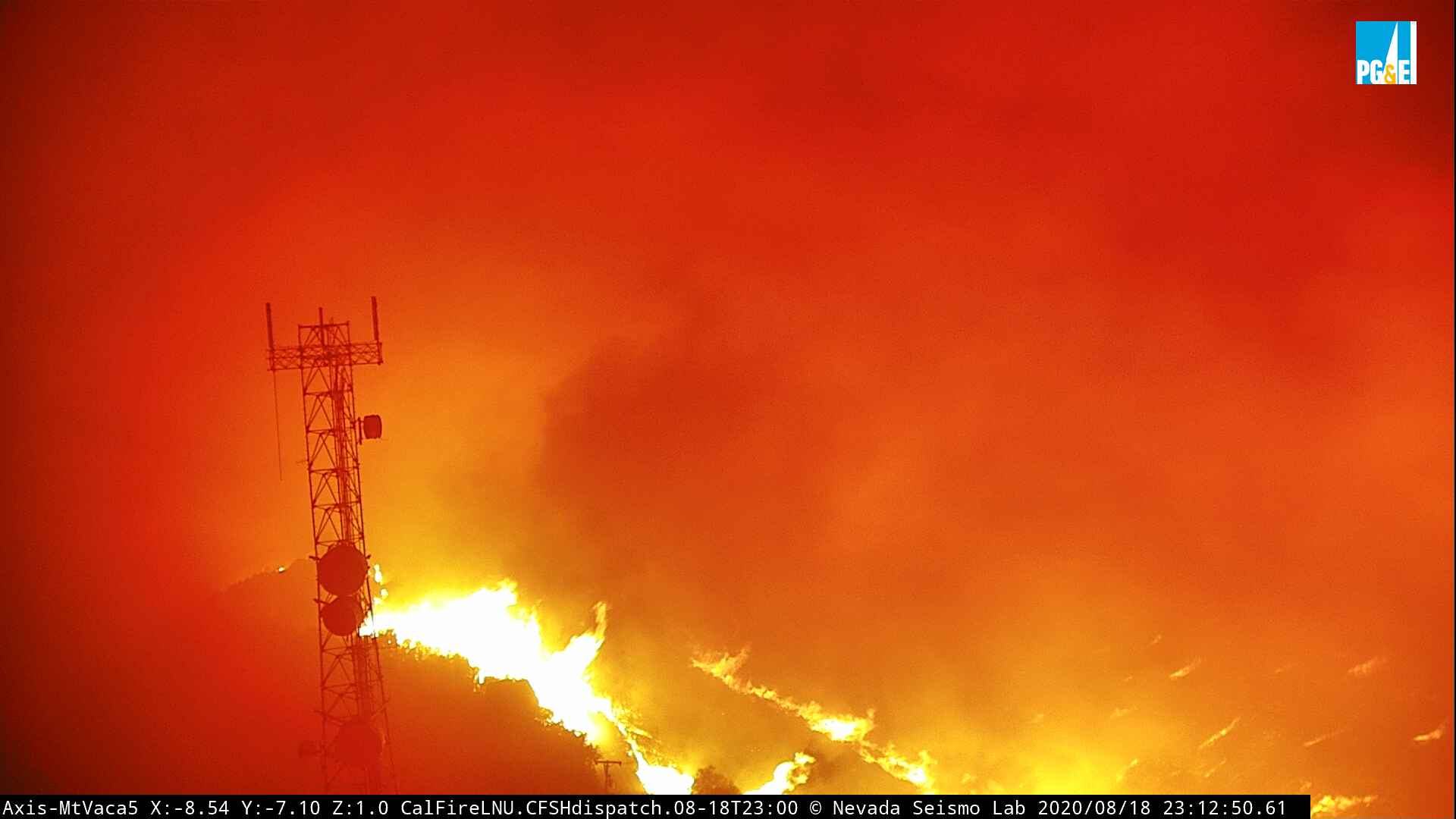

Every single view of the fires, from professional photographers on the front lines to satellites 35,406 km out in space, has captured the alarming scope of the flames. But some of the most visceral footage has come from time-lapse cameras mounted in the foothills and mountains that have been overrun by flames. Sitting in my New York apartment on Monday and watching the time-lapse of the LNU Lightning Complex wildfire marching over a hill and flaring up right into the camera lens until one last pyrrhic moment, I could almost feel the heat as I involuntarily shrunk back from the screen.

The cameras aren’t just there to provide a rush to those of us lucky enough to be 4,828 km away. They’re part of a network called ALERTWildfire, created by seismologists who, as Graham Kent, director of the Nevada Seismological Laboratory, quipped, “got tired of waiting for the Big One.” As it turns out, the Big One isn’t the earthquake that will cleave California into the sea. It’s wildfires overrunning the state in our increasingly hot and volatile climate.

The ALERTWildfire network was designed to help firefighters identify nascent blazes and put them out. Initially piloted in the Lake Tahoe area, it’s since expanded to cover the entire state of California plus Nevada and Oregon. In the past two years alone, 600 new cameras have been installed. The gear is a standard surveillance camera with tilt and zoom features, and the streams from each site are fed live to ALERTWildfire.

That allows fire dispatchers to verify fires that are called in and quickly send whatever resources are necessary to put them out. Kent said a volunteer network has sprung up in Orange County, with about 400 everyday folks monitoring the camera feeds in shifts on red alert days when fire danger is high.

In a hot world where resources to fight fires are precious — both because firefighting budgets are maxed out and because large fires have become more common and widespread — the concept makes perfect sense. Fire managers could target flames with just the right touch and evacuate areas as needed. But this week’s powder keg has overwhelmed both firefighters and the camera system.

“Up until this kind of year, it was like you get a 911 [call], you get a confirmation with a camera, they send in an airstrike. They decapitate the fire early and on to the next one,” Kent said, “Now, it becomes a triage tool.”

The firestorm that has engulfed California is hard to put into perspective. At least 560 wildfires were lit by a bizarre lightning storm that accompanied record-setting heat. Two of the fires ignited this week are already among the largest fires in state history.

A small town’s worth of firefighters (at least 12,000 as of writing) have been dispatched across the state like a gossamer fabric trying to hold back a wall of flames. Tens of thousands of structures are in harm’s way, and millions of people across the state have evacuated, been left on edge, lost power in rolling blackouts, or some combination of all three, all in the middle of a pandemic. It’s a cascading crisis with no end in sight, particularly ahead of the dreaded fall Santa Ana and Diablo winds, when most fires ignite.

Kent said that as of Friday, 10 of the group’s cameras have been burned over. But having the ability to monitor hundreds of other cameras is still an asset most states and even countries would dream of. Last year, the network of cameras allowed fire managers to evacuate people in the path of the Kincade Fire, resulting in zero casualties in the first 24 hours of the widespread evacuation, a first.

In comparison, Australia had nothing of the sort to guide it through the catastrophic bushfire season this past austral summer. At least 30 people died directly from the Australian fires and 445 died from smoke-related illnesses, while dramatic scenes of thousands trapped on beaches under blood-red skies reflected the lack of early evacuation warnings.

Firefighters and communities living in a fire-prone landscape will always be the first to benefit from a system like ALERTWildfire, something that can literally save lives by providing precious minutes of lead time to evacuate. But I also keep coming back to it as a tool to understand the gravity of the crisis we face. These cameras are bearing witness to a climate unprecedented in human history, one brought about by Big Oil’s lies, utilities’ greed, and a rapacious system of growth tied with fossil fuels. They convey something visceral and primal, something I feel powerfully watching the towering plumes of smoke and hungry flames eating everything in their path as the cameras tilt and zoom, trying to centre the fire.

Kent likened the camera’s attempts to get a view of the flames to our own struggle to grasp the situation. “The camera is trying to see what’s going on, so it’s like almost like a human panicking,” he said. “We’re really on an escalating tragedy and it’s going to get worse on average every year.”

I felt that same panic and sense of tragedy watching the fires this week, although I was sitting thousands of miles away from them. In a world where these massive fires are only becoming more frequent, and those in charge of protecting us lack the resources to do so, there’s plenty of room for that fear — and need for action before the rising heat everywhere on Earth overwhelms us all.