There were once hundreds of thousands of sea otters in the Pacific Northwest. Indigenous people hunted them sustainably for thousands of years. But in the 1740s, with the advent of the Pacific Maritime Fur Trade, people began hunting them at a far larger scale, selling their thick, luxurious fur for increasing profits. By the late 19th century, they were almost extinct.

A new study weighs the economic costs and benefits of reintroducing sea otters into the North Pacific region. Looking at a small corner of British Columbia, it finds bringing otters back would yield nearly $US40 ($58) million in new economic benefits and be good for ecosystems and the climate.

As otters disappeared, it resulted in big ecological changes. Sea otters eat up to a third of their body weight per day, and their foods of choice include crabs, clams and sea urchins. With no sea otters around to eat them, populations of shellfish grew. Fishermen took advantage of that by opening new fisheries along the Canadian Pacific coast. Now, thanks to restoration projects in the 1960s and 1970s, otters are making a comeback in the area, which has led to transformational changes. In the paper, a team led by University of British Columbia professor Edward Gregr examine whether those changes are economically a net-positive.

[referenced url=”https://gizmodo.com.au/2020/06/trumps-latest-rollback-will-allow-hunters-to-shoot-wolf-pups-and-bear-cubs-in-their-dens/” thumb=”https://gizmodo.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/10/h2wzwptcpmkvazcrdma1-300×169.jpg” title=”Trump’s Latest Rollback Will Allow Hunters to Shoot Wolf Pups and Bear Cubs in Their Dens” excerpt=”The Trump administration is finalising a rule that will put animals in Alaska’s national preserves — including black bears, wolves and coyotes — in danger. The change will allow hunters to use cruel tactics, including luring hibernating bears out of their dens with bacon and doughnuts and entering wolf dens…”]

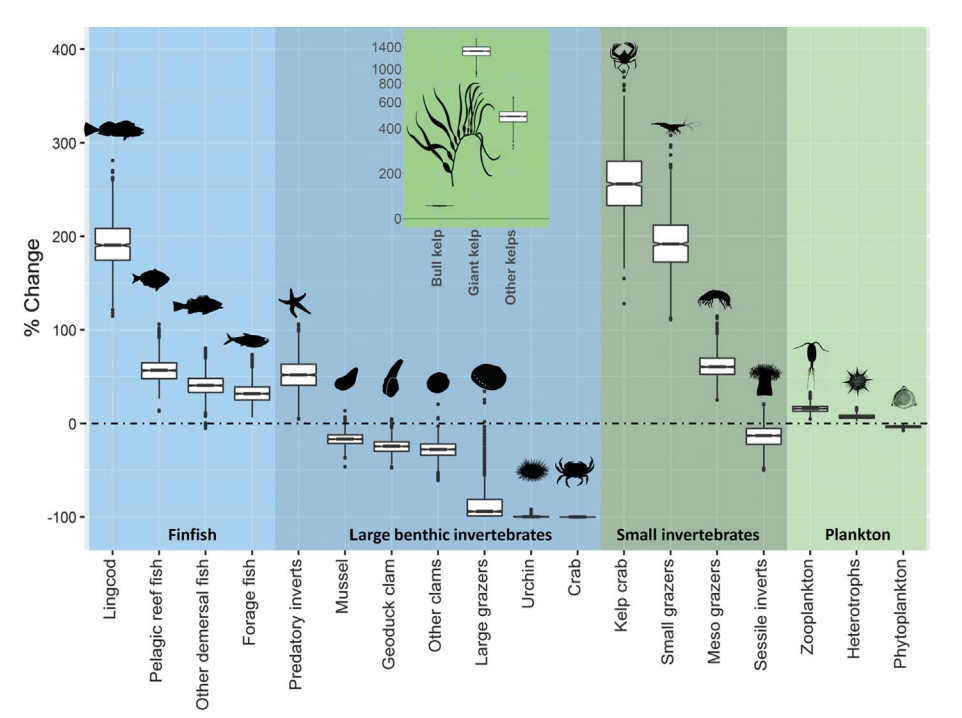

Otters eat shellfish and shellfish eat kelp. Kelp forests provide shelter to tons of marine animals and also suck carbon out of the atmosphere. With sea otters lowering shellfish populations, kelp forest ecosystems are beginning to thrive. That helps sequester carbon and also creates healthier habitats for finfish such as rockfish, greenlings, and salmon. Plus, since sea otters are super playful and cute and smart, tourists flock to come see them. That all creates economic benefits.

But with far fewer shellfish to catch — including valuable ones like geoduck and Dungeness crab — the reintroduction of sea otters could threaten well-established fisheries and the shellfish economy. That’s set up a conflict, one that the new paper published in Science on Wednesday attempts to disentangle.

The scientists developed a modelling framework to weigh the impact of otters on shellfish fisheries against the economic benefits of reintroducing the creatures. Focusing on the west coast of Vancouver Island, the team combined field data, food web dynamics, and economic data to show a clear picture of the region without otters versus with them.

The findings suggest that the overall monetary value of increased tourism, finfish fisheries, and carbon sequestration will far exceed the losses to impacted commercial fisheries. Salmon, rockfish, and greening fisheries and carbon capture came with big economic benefits, and to the authors surprise, the biggest benefit was increased tourism. The authors found that while the losses to shellfish fisheries would total about $US5.4 ($8) million, the benefits of reintroducing otters would total $US39.6 ($58) million.

“We expected the recovery of kelp to have considerable value, so we were pleased that the ecological results reflected our understanding,” Gregr told Gizmodo in an email. “But we were a bit surprised by how much more tourists were willing to pay for sea otters.”

Though the findings show bringing otters back is a net benefit overall, the authors found that those benefits aren’t distributed equally. Indigenous people won’t be helped by, for instance, the boon to tourism since tourists won’t likely visit their lands. At the same time, tribes have farmed shellfish in the area as a way to generate income. The reintroduction of sea otters could cut into that income. Any reintroduction program needs to take that into account and create programs to more equitably distribute the benefits and find alternate opportunities for revenue.

The study focuses on Vancouver island specifically, so the specific costs and benefits of otter reintroduction may vary in different localities. But the authors hope their cost-benefit model will prove helpful for conservationists who are working to restore populations of the creatures elsewhere. It could also help model the economic impact of reintroducing other animals, especially those that like sea otters are at the top of the food chain.

“Apex predators tend to influence the structure of ecosystems,” said Gregr, which can make reintroducing them complicated. “The reintroduction of wolves in Yellowstone Park has had similarly dramatic effects.”

Indeed, like hunting of sea otters led to the spread of crabs and clams which in turn depleted kelp forests, hunting of grey wolves in the West helped coyote populations thrive which depleted fox populations along with a host of other impacts. By creating a model to weigh the costs and benefits of conservation, the authors hope to help policymakers make more informed decisions.

Of course, economic benefits aren’t the only ones policymakers should weigh. In the face of a rapidly worsening climate crisis, carbon sequestration, for instance, has benefits beyond money. But this new study shows how conservationists can work to ensure that ocean and climate policy doesn’t come at the expense of vulnerable communities.

“This day and age, unfortunately, we often need to put dollar amounts to ecosystems, stocks of recovering species, and the services provided by them, to justify conservation,” Brent Hughes, an ecologist at Sonoma State University who didn’t work on the study, told Gizmodo in an email. But since some factors transcend economic benefits or costs, like the impacts to First Nations peoples’ life-sustaining shellfisheries, he noted the importance of engaging impacted communities in conservation planning.