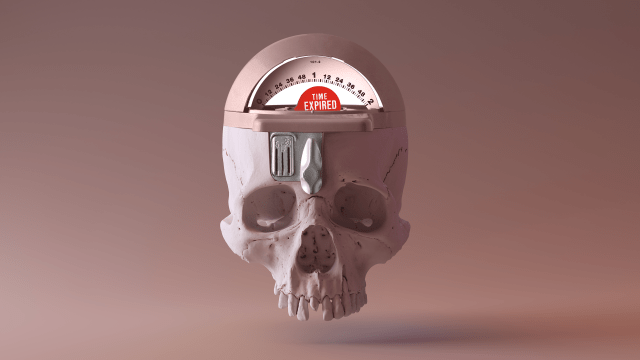

We all know the U.S. healthcare system is unequal and inhumane, but apparently your income can determine your lifespan even in places with fairly good healthcare. A new report from the UK shows that, despite ostensibly equal access to healthcare, people with a lower income and who live in less affluent areas have shorter lives by nearly 10 years.

The report, “Health Equity in England,” is based on epidemiological surveys in the UK and shows that in the most economically depressed 10 per cent of the country, life expectancy is the shortest, while in neighbourhoods representing the wealthiest 10 per cent, life expectancy is the longest. Moreover, in the last decade, that health gap has gotten worse, and the expected increase in life expectancy has stalled overall—the first time that has happened in the UK in 100 years.

As Sir Michael Marmot, a professor of epidemiology at University College London and the principal author of the report, told Gizmodo: “There is more bad news than good.”

In countries like the U.S., where individuals have to pay huge sums for medical services, inequities in health and therefore in lifespan between the richest and poorest may not be surprising. But the fact that this rich vs. poor divide exists in the UK highlights how money influences nearly everything about a person’s experience on this planet.

“Health Equity in England: The Marmot Review 10 Years On” is an assessment—some might say an indictment—of society’s progress since the original report on the issue of health inequality in the UK appeared back in 2010. According to the update, there has been little improvement in fixing the health gap between rich and poor.

Indeed, the disparity in life expectancies has widened in the last 10 years. For the years between 2010 and 2012, for example, the wealthiest men could expect to live 9.1 years longer than men in the poorest group; for women, the difference between rich and poor was 6.8 years. Fast forward to 2016 to 2018, and the difference in life expectancy at birth between the wealthiest and poorest increased to 9.5 years for men and 7.7 years for women.

Put another way, men living in the most deprived parts of England might expect to live to be 73.9 years old, while those living in wealthiest neighbourhoods of London might expect to live to be 83.4 years old. While life expectancy for women continues to be longer than for men, the mortality gap persists here, too, with the poorest women expected to make it to 78.6 years old while those more financially well off may make it to 86.3 years old.

As the economic differences get more extreme, so do the health extremes, said Marmot at a seminar in Paris held by the National Press Foundation ahead of the report’s release: “The poorest 10 per cent of women are dead at 75, while the richest 10 per cent live until 87.”

It’s not a matter of simply affording better doctors. It’s the complete socio-economic environment, which includes not only better access to healthcare but also better education (which leads to better health choices), better air quality (deprived areas tend to suffer from more pollution), and a better overall quality of life. The report mentions that while it is difficult to pinpoint a single economically related cause, poverty is harmful to health in many ways, ranging from not being able to properly heat your home to not being able to afford a nutritious diet to being deprived of rest and relaxation.

While the Marmot report focuses on the UK, many of its insights can be applied elsewhere. The authors note, rather ominously, that the slowdown in life expectancy improvement in the UK is more marked than in any other high-income country—with the notable exception of the United States. Furthermore, the report mentions that death rates are increasing for men and women aged 45 to 49, “perhaps related to so-called ‘deaths of despair’ (suicide, drugs and alcohol abuse) as seen in the USA.”

[referenced url=” thumb=” title=” excerpt=”]

And what of the so-called expense of receiving possibly life-saving vaccines against infectious diseases like the new coronavirus?

In most countries (with the exception of the U.S.), the cost of any future COVID-19 vaccine won’t be a factor for those who want to receive it. Since it would fall under existing coverage, production volumes to meet the demand will be more important. However, the Marmot report suggests that those people already in economically disadvantaged positions could be further harmed should they become ill thanks to COVID-19. For those people, missing work because of sickness or a quarantine would directly reduce their income and so have further detrimental effects on life and livelihood.

Aside from the obvious idea that if you want better health outcomes, you need to make more money, what can be done?

Marmot’s original report in 2010 made several recommendations, many of which focused on attacking the roots of poverty early: better wages, the elimination of marginal jobs, and support for early childhood learning to reduce the effects of poverty. While the UK government reduced budgets aimed at such efforts in the past decade, there were some municipal pockets of hope, according to the report. Unfortunately, they were the exceptions rather than the rule.

JQ (@jqontech) writes about science and technology and is the editor-in-chief of OntheRoadtoAutonomy.com.