A plethora of previously unknown bacterial strains related to chlamydia have been found in the unlikeliest of places: sediment under the Arctic seafloor. The discovery is posing new questions about this diverse and durable group of bacteria and how they came to infect humans and other animals.

Chlamydia is the most commonly reported STD in the United States, and it’s caused by an infection of the Chlamydia trachomatis bacterium. Since 1994, chlamydia has constituted the largest proportion of all STDs reported to the U.S. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention.

This bacterium and its related cousins, collectively known as Chlamydiae, can also infect other organisms, which lets them survive and replicate. Scientists call them “obligate intracellular parasites,” which means they can only reproduce inside a host cell. In addition to humans and other animals (such as koalas), Chlamydiae prey on microorganisms more complex than themselves, namely marine eukaryotes such as amoeba, algae, and plankton.

Chlamydiae are known to inhabit a wide range of habitats, but as new research published in Current Biology shows, their ecological range is far more diverse than we ever imagined. The new paper, led by microbiologist Thijs Ettema from Wageningen University & Research in The Netherlands, shows that a diverse population of Chlamydiae exists in the high-pressure, low-oxygen sediments under the Arctic seafloor.

“Finding Chlamydiae in this environment was completely unexpected, and of course begged the question, what on Earth were they doing there?” asked Jennah Dharamshi, a researcher from Sweden’s Uppsala University and the first author of the new study, in a press release.

The unusual location of the Chlamydiae points to the durability and flexibility of this bacterial group, while also offering new insights into its evolution and how it came to infect macroorganisms like humans. That said, the researchers weren’t able to identify any hosts within the marine sediment, nor were they able to grow any of the newly discovered Chlamydiae in their lab (it’s not easy to simulate the high-pressure, low-oxygen environment in which they were found). It’s also not immediately clear how this bacteria made its way from the deep ocean and into our genitals, if that’s indeed the pathway taken. In fairness, the new paper tends to ask more questions than it answers, highlighting some exciting new avenues of exploration and scientific inquiry.

“Chlamydiae have likely been missed in many prior surveys of microbial diversity,” said Daniel Tamari, a co-author of the study and a researcher at Wageningen University & Research, in the press release. “This group of bacteria could be playing a much larger role in marine ecology than we previously thought.”

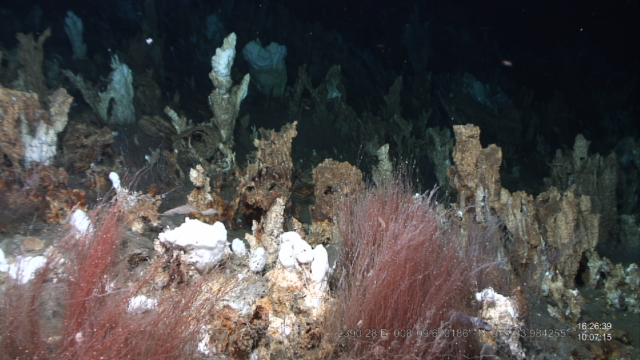

The previously unknown lineages of Chlamydiae were found to “dominate microbial communities” in deep, oxygen-deprived (anoxic) marine sediments, according to the new paper. These sediments were located at Loki’s Castle, a series of deep-sea hydrothermal vents located between Norway and Greenland. The bacteria were found in sample cores located several feet below the seafloor—an environment exclusive to microorganisms (as opposed to larger animals, such as brittle stars or clams).

Analysis of the samples showed that upwards of 43 per cent of all bacteria found in the sediment were members of Chlamydiae. At such large quantities, it likely means these microorganisms are having a serious impact on the local ecology of this oxygen-starved environment. In total, the researchers were able to identify 163 unique species of Chlamydiae, of which one was found to be a close relative of Chlamydia trachomatis, the bacterium responsible for the STD in humans.

“Finding that Chlamydia have marine sediment relatives, has given us new insights into how chlamydial pathogens evolved,” said Dharamshi.

As noted, the researchers weren’t able to find any eukaryotic hosts in the samples, so they’re not certain which species they’re dependent upon. That said, a preliminary genetic analysis of the samples suggests they have the physiological traits required of obligate intracellular parasites. The hosts, therefore, must exist—they just have to be found.

“Every time we explore a different environment, we discover groups of microbes that are new to science. This tells us just how much is still left to discover,” said Ettema.