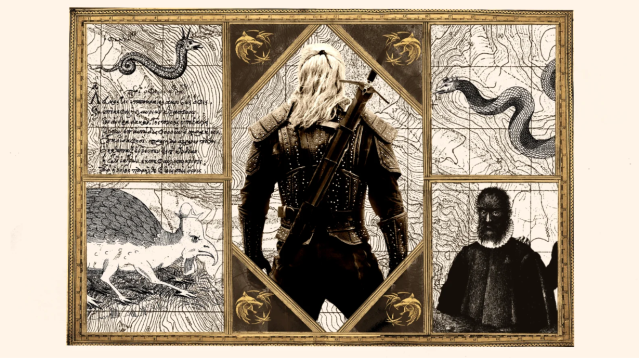

Andrzej Sapkowski’s The Witcher is getting a lot of attention these days and come December 20, you can expect even more. Let’s explore the medieval folklore that inspired The Witcher saga”the monsters, the heroics and the trouble with being a freelance monster hunter.

Netflix’s upcoming series The Witcher, based on Polish author Sapkowski’s bestselling series of novels and short stories, centres on the story of Geralt of Rivia, a “Witcher” who hunts magical beasts for pay. It’s #GigLife or, as Sapkowski defines the job in The Last Wish, “itinerant killers of basilisks; travelling slayers of dragons and vodniks.” Basically, think of Geralt as a supernatural bounty hunter.

And, there are dragons, lots of dragons, and basilisks and strigas and elves and dwarves and witches. Game of Thrones took its sweet ol’ time before leaning into the more fantastical elements of the series. With The Witcher, there will be a smörgÃ¥sbord of fantastic creatures from the outset.

The Witcher‘s origin story

The year was 1985. Sapkowski was a 38-year-old travelling furs salesman who decided to enter a Polish short story competition. He had 30 pages and thought he’d retell the Polish myth of the cobbler who defeats the Wawel Dragon. In the tale, the cobbler poisons the dragon with a sulphur-laced sheep. Upon eating said sheep, the dragon freaks out and drinks so much water it bursts. It’s your classic underdog story.

Sapkowski, ever the realist, found the story unbelievable. “Poor cobblers make good shoes, they don’t kill monsters,” Sapkowski told Eurogamer. “Soldiers and knights?” he goes on to say, “They are idiots generally. And priests want only the money and fucking adolescents. So who’s killing monsters? Professionals. You don’t call poor cobblers’ apprentices: you call for professionals. So then I invented the professional.” And so, The Witcher saga was born, and Geralt, the professional monster killer, with it.

Welcome to the Continent

Geralt’s world is known simply as “the continent” and it’s a bit of a Europe lookalike modelled (like much of the folklore behind The Witcher) around Eastern Europe and Scandinavia.

Gnomes and dwarves were the first inhabitants of the continent. Then, the elves joined them. The gnomes, dwarves, and elves”known by humans collectively as the Elder Races”figured out how to coexist with relative ease. That is, until the humans arrived to mess everything up. (Go figure!) The humans went to war with the elder races, levelling much of their civilisations in the process. The survivors were left to either adapt into prejudiced human society, retreat to their own enclaves away from human civilisation, or join the Scoia’tael, a group of anti-human guerrilla fighters rebelling against their persecution.

Conjunction of Spheres

Mass upheaval of the Continent’s societies was not the only chaotic element of the human age. The arrival of the humans coincides in The Witcher with a huge event known as the Conjunction of Spheres, which can rival the Avengers films in multiverse jargon. During the Conjunction of Spheres, portals were opened to new realms allowing beasts and creatures from other worlds to come into our own. The Conjunction also allowed magic into the continent, which in The Witcher is essentially the ability to control chaos energy that permeates the world and gives it form.

The Conjunction of Spheres also means that Geralt can go out and kill all these monsters and it won’t affect his world’s ecosystem. Basically, these monsters are an invasive species” killing them is for the good of the continent.

The idea of a multiverse can be traced back to many religious traditions. In ancient Egypt, the snake Apophis personifies the chaos of Duat, the Egyptian realm of the dead; the same sort of Chaos that breaks into Geralt’s world during the Conjunction. In Mormonism, Apostle Orson Pratt claimed, “world, and systems of worlds, and universes of worlds existed in the boundless heights and depths of immensity.” Is your head spinning with multiverse-speak yet?

While Polish folklore inspired much of The Witcher and the Conjunction’s concept of the multiverse can be found in many religious traditions, it’s Celtic lore that inspires the backdrop to Sapkowski’s series. Like in The Witcher, the legendary Celts epically faced off with the elves for control of Ireland.

The Celtic myth can be found in The Book of Invasions (or Lebor Gabala Erenn in Irish), the complete text of which can be found in the 12th century Book of Leinster though the tale dates back much, much earlier.

According to The Book of Invasions, everyone from Noah’s granddaughter to single-armed and single-legged monsters populated Ireland at some point. But, it’s the arrival of the Tuatha De Dannan, aka Irish elves, that seems to have most inspired Sapkowski.

The Tuatha De Dannan arrive in Ireland like bosses, cloaked in dark clouds and armed with magic. The Fir Bolg, a humanoid race who had been squatting on Ireland up till now, didn’t stand a chance. The Tuatha De Dannan successfully took over the Emerald Isle until humans arrive on the scene. After wandering through Spain and Egypt, the Gaels (aka Celts, aka humans) were looking to put down some roots and set their sights on Ireland.

After the Gaels arrive in Ireland, the Tuatha De Dannan convinced them to return to their ships. (It’s not entirely clear how, but they’re magical elves so I guess they may have some tricks up their elven sleeves.) A battle of magical incantation ensues as the Tuatha De Dannan’s sorcerers build the waves up to drive back the Gaels. But the Gaels’ sorcerers prevailed, driving the Tuatha De Dannan beneath the sid (fairy) mounds, tiny hills where they remain hidden in an invisible world beneath the ground to this day (or so the story goes).

Yes, there are elves in Eastern European folklore too. But, it’s in the Celtic legend where humans and elves face off in an epic battle like that mentioned in The Witcher. Also, the names of both the Tuatha De Dannan and Sapkowski’s elves in The Witcher saga are nearly identical. The elves in the novels are known as the Aen Seidhe. Another name for the Tuatha De Dannan? The Aes SÃdhe. The accented “Ô means the two names are pronounced very similarly as well.

Despite The Witcher‘s elves having Celtic roots, the series is full of creatures from Polish folklore. Geralt needs some monsters to hunt, does he not? And, Sapkowski’s world is so vivid that you may start fearing a vodkin attack next time you take a walk in the woods.

The striga

First up is the striga, a woman cursed to become a werewolf/vampire/witch hybrid and hunt humans by the full moon.

In The Last Wish, the first book of Sapkowski’s saga, a king and his sister have a daughter. (Feeling the Jaime and Cersei vibes, yet?) Due to her incestuous birth, the poor girl is doomed to become the monstrous striga whenever the moon’s full. Geralt is tasked with finding and curing, or”if curing proves impossible” killing the princess-striga.

As you might imagine, the striga isn’t something you want to bump into on a dark night. In The Witcher, the loud-mouthed Velerad describes, “Her Royal Highness, the cursed royal bastard, is four cubits high, shaped like a barrel of beer, has a maw which stretches from ear to ear and is full of dagger-like teeth, has red eyes and a red mop of hair! Her paws, with claws like a wild cat’s, hang down to the ground!” It also comes out that Sapkowski’s striga only ventures beyond the castle’s crypt on full moons and hates silver. Sound familiar? A little werewolf-ish perhaps?

The striga is a Polish cocktail of werewolf and vampire legends that spread throughout Medieval Europe. As scholar Brian Cooper points out in his The Word “vampire”: Its Slavonic Form and Origin, the Slavic word for vampire, “vampiru,” got confused with the word for wolf-man, “vlukodlaku.”

Sapkowski didn’t just borrow the striga from Polish folklore, but remixed another Polish folklorist’s story as well. As academic Dorota Michulka points out in her Looking for Identity: Polish Children Fantasy Then and Now, Sapkowski lifts his story of the striga from Roman Zmorski’s Strzyga. Zmorski, a Polish folklorist, writer, and translator of the Romantic era, was deeply fascinated by Polish myth and legend like Sapkowski.

In both Zmorski and Sapkowski’s tales, the striga is the by-product of the king’s incestuous relationship with his sister. In both stories, the king seeks a hero who can cure his daughter offering her hand in marriage as a reward.

[referenced url=” thumb=” title=” excerpt=”]

The difference between the two stories comes from the hero that steps up to the challenge. In Zmorski’s telling, the hero is a handsome orphan who accepts the daughter as a “reward.” In Sapkowski’s, the hero is the white-haired, monster bounty hunter, Geralt the Witcher, who’s only interested in the money offered as a reward.

The basilisk

In Sapkowski’s second collection of short stories, The Sword of Destiny, the basilisk, another creature from Polish folklore, rears its ugly cockerel head. Yup, the same basilisk that makes an appearance in the Harry Potter series, the same basilisk that was last reportedly seen alive in medieval Warsaw!

It’s 1587 and monsters are a very real part of the medieval worldview. Real people with little-understood physical differences were touted around to various royal courts, like Pedro Gonzales, “the werewolf of the Canaries,” who was adopted by the French Court. And, come 1587 in Warsaw, a Polish man reportedly kills a basilisk with a mirror, turning the creature’s deathly gaze on itself.

According to legend, the basilisk was a snake-like beast with the head of a cockerel and its gaze was deadly. According to a 12th century bestiary, “If it looks at a man, it destroys him,” though references to the basilisk, the king of snakes, date as far back to Pliny the Elder in 79 CE.

Just like with the striga, Sapkowski doesn’t just borrow the monster, but remixes the entire Polish legend too. In The Sword of Destiny, a character protests, “you can’t kill a basilisk without a looking glass, everyone knows that””Sapkowski’s nod to the Warsaw legend. But, Geralt takes no mirror with him to defeat the basilisk, only his sword.

He doesn’t need a mirror, as the Journal Bestiary for The Witcher video game contends: “witchers… [find] it is far better to smash the mirror on the creature’s head.” Once again, Geralt defeats these monsters with brute force and honed skill making the Witcher world all the more vivid and grounded. Yes, there are dragons and basilisks and strigas, but they can be killed like any other creature.

The dragon and the cobblerÂ

Speaking of killing dragons, in another story from The Sword of Destiny, Sapkowski riffs on the Polish legend of the cobbler who defeats the dragon, the folktale that inspired the whole Witcher saga we mentioned earlier. It’s a moment that epitomizes Sapkowski’s world of fantasy, but also a world with a realist like Geralt at its heart. Despite the fantastical elements in The Witcher, Geralt is as straight-shooting as the bounty hunters and outlaws of old Hollywood Westerns.

The earliest telling of the Wawel Dragon dates back to 13th century Poland and has no mention of a cobbler. Instead, the king’s two sons defeat the dragon with the same sulphur poisoned calf that, in later retellings, the poor cobbler will use to defeat the dragon. It’s not until Marcin Bielski’s 16th century retelling that the cobbler will replace the king’s sons as the unlikely hero of the story.

Sapkowski retells the Polish legend of the Wawel Dragon like your friend who never believes your most epic going-out stories. The wise bard, Dandelion, who relates the story to Geralt, is just as surprised as the townspeople that the dragon actually ate the cobbler’s poisoned sheep “which stank to high heavens” and was held up by a stake. But the poisoned sheep was not enough to kill the dragon and thus begins Geralt’s own adventures with the dragon. In the books, King Niedamir sends out a contingent to kill the dragon in a political move in order to be seen as a dragon killer and fulfil a prophecy to gain land and power.

The professional

But, Geralt doesn’t kill dragons. It goes against his code of honour. So, the one monster you’d expect a medieval knight to go after, Geralt isn’t about to slay. Sapkowski isn’t going to play into your typical medieval fantasy archetype.

Geralt isn’t some romantic, ironclad knight. He’s an 85-plus-year-old Witcher, who doesn’t have time for your court intrigue or power struggles. Geralt could care less about King Niedamir or dragon-killing, and only goes on this whole dragon crusade because he heard his lady friend, Yennefer, was going. Geralt is a free agent, who only cares about collecting his bounty. With a projected lifespan of a couple hundred years, he isn’t about to get wrapped in some political drama of the moment. He has a job to do. He knows how to do it. So, don’t get in his way, ok?

That is, at least until those he cares about get wrapped up in the political drama themselves”thus beginning Geralt’s character arc. In a world teaming with strigas, basilisks, and dragons, a world subject to genocide, political infighting, and a collision of dimensions threatening the very fabric of reality, Geralt still does his best to ignore the BS.

Sarah Durn is a freelance writer, actor, and medievalist based in New Orleans, LA. She is the author of the upcoming book “A Beginner’s Guide To Alchemy” to be published in Spring 2020.