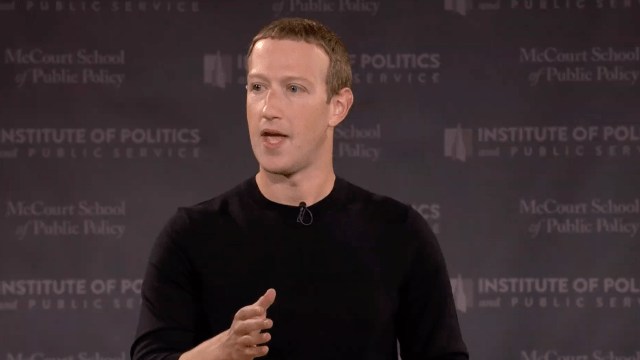

Addressing a group of rightfully bored-looking Georgetown students, one of whom was allegedly escorted out for failing to silence their phone, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg used his much-anticipated speaking engagement Friday primarily to try to rewrite the history of his data collection company.

Zuckerberg framed Facebook’s failure to enter the Chinese market as an unwillingness to compromise on the importance of free expression, its new oversight board a piece of responsible corporate governance enacted to the benefit of users everywhere. And perhaps most staggering: the notion was floated that, had Mark only gotten to work a few years sooner, Facebook could have prevented America’s blundering forever war in the Middle East (emphasis ours):

Back when I was in college our country had just gone to war in Iraq and the mood on our campus was disbelief. [A] Lot of people felt like we were acting without hearing a lot of important perspectives, and the toll on soldiers and their families and our national psyche was severe, yet most of us felt like we were powerless to do anything about it.

And I remember feeling that if more people had a voice to share their experiences, then maybe it coulda gone differently. Those early years shaped my belief that giving everyone a voice empowers the powerless and pushes society to be better over time.

Back then, I was building an early version of Facebook for my community, and I got to see my beliefs play out at smaller scale. When students got to express who they were and what mattered to them, they organised more social events, started more businesses, and even challenged some established ways of doing things on campus.

It taught me that while the world’s attention focuses on major events and institutions, the bigger story is that most progress in our lives comes from regular people having more of a voice.

Since then, I’ve focused on building services to do two things: give people voice, and bring people together.

In reality, Zuckerberg tried damn near everything to capture China’s 1.3 billion potential users, up to and including reportedly offering to let President Xi Jinping name his then-unborn daughter. (Xi apparently declined.)

Facebook’s oversight board is a provision of the company’s historic $7 billion settlement with the FTC, the result of government probes into the Cambridge Analytica scandal, rather than something merely dreamt up to improve moderation. That Facebook — an app initially created to rate the relative physical attractiveness of women at Harvard — could act as a global olive branch is ridiculous on its face.

What makes Zuckerberg’s implication that the Iraq War was an aberration caused by inadequate access to speech, or a vacuum of perspectives, in any way notable is that it represents a bold step from corporate hagiography to outright speculative fiction.

This risky strategy comes at a time when Facebook has never been in greater danger of being regulated, so it benefits the company, no matter how ridiculous the strategy, to rhetorically tether itself to the idea of free expression. But undermining that line of attack were the same milestones of social progress Zuckerberg repeatedly, gratingly draped himself in.

Notably absent during the time of the Civil Rights Movement, landmark First Amendment cases Schenck v. United States and New York Times v. Sullivan, or an overwhelming majority of skirmishes in “the fight for democracy worldwide”? Facebook, or social media of any kind.

In times of social tension, our impulse is often to pull back on free expression, because we want the progress that comes from free expression but we don’t want the tension. We saw this when Martin Luther King Jr. wrote his famous letter from a Birmingham jail where he was unconstitutionally jailed for protesting peacefully. And we saw this in the effort to shut down campus protests during the Vietnam War.

We saw this way back when America was deeply polarised about its role in World War 1 and the Supreme Court ruled at the time that the socialist leader Eugene Debs could be imprisoned for making an anti-war speech. […] We’re at another crossroads. We can either continue to stand for free expression, understanding its messiness but believing that the long journey towards greater progress requires confronting ideas that challenge us. Or we can decide that the cost is simply too great.

Of course, the implicit assumption is that any of these missteps might have hypothetically been prevented by more and more varied speech — a riff of the classic technocrat argument that the antidote for bad speech is good speech, in much the way a “good guy with a gun” supposedly prevents murders.

But more worryingly, Facebook sets itself as the arbiter of free expression, potentially one more equitable than the government in these three ahistorical examples. “You’re being hysterical. Are you for civil rights or against Facebook?” Zuckerberg seems to ask, offering a false moral equivalency between social progress and unfettered capitalism.

That Zuckerberg frames the Vietnam backlash or the Civil Rights Movement as speech issues first and foremost, rather than a reaction to being forcibly conscripted into the military through the draft and people of colour being denied equal rights, respectively, is its own much deeper problem.

That this speech proselytising the value of free expression (on Facebook) was followed by a question-and-answer segment in which journalists were barred from making inquiries, and Georgetown students had theirs vetted ahead of time, betrays the precise depth of Zuckerberg’s commitment to these ideals.

He’s correct about one thing though: We are in a time of social tension, driven at least in part by social media, and largely by the massive wealth disparity between the rich and poor in this country and abroad. Billionaires who have found ever more efficient ways to extract value — through labour or data — are largely to blame for the anger and powerlessness many people feel now.

Zuckerberg claims to have felt similarly watching the Bush administration send thousands to die halfway across the world, leaving a decade of almost indiscriminate carnage in its wake. Today, more often people are relatively powerless to stop Zuckerberg and those like him from constantly surveilling and monetising their every quantifiable action.

People had a voice before Facebook. They will have one after Facebook. And their ability to express themselves freely does not grow or wane with the scale of the company’s monopoly on expression — arguably, the inverse is true. It’s easy to mock Mark Zuckerberg’s awkward delivery, eerily smooth features and robotic mannerisms — and as a public figure with immense power and remarkably poor judgment, he deserves all the derision that can be heaped upon him — but beneath all that, he is without a doubt one of the most dangerous people alive.

His increasingly stentorian attempts at psychological manipulation will only further cement his legacy as one of history’s greatest heels.