Rapture Reef was an undersea Eden, hundreds of miles out in a remote, ocean wilderness. It was a pristine, coral wonderland, renowned among marine biologists. But now it’s gone. This month, stunned scientists discovered that a hurricane wiped Rapture Reef off the map last spring.

Researchers with the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and their partner scientists returned earlier this month from a 22-day expedition in the Papah?naumoku?kea Marine National Monument, an Alaska-sized protected tract of ocean and coral atolls northwest of the main Hawaiian Islands.

The scientists’ primary mission was to collect additional specimens of new species of algae and see how reefs around uninhabited Lisianski Island was recovering from a brutal coral bleaching event in 2014.

But Randy Kosaki, NOAA’s Deputy Superintendent of the Monument, told Gizmodo that both those missions felt a hiccup when the researchers reached French Frigate Shoals, Papah?naumoku?kea’s largest atoll and home to Rapture Reef, arguably the crown jewel of the archipelago’s reef system.

In October 2018, nearly annihilating an entire island. But no biologists had been in the waters around French Frigate Shoals since then.

“We were expecting some storm damage, some broken coral,” recounted Kosaki, but nothing could have prepared them for their reunion with Rapture Reef. “For Rapture Reef to be wiped off the face of the Earth, it was like a punch in the gut.”

Kailey Pascoe — a researcher at the University of Hawai’i at Hilo — was among the first to revisit the site.

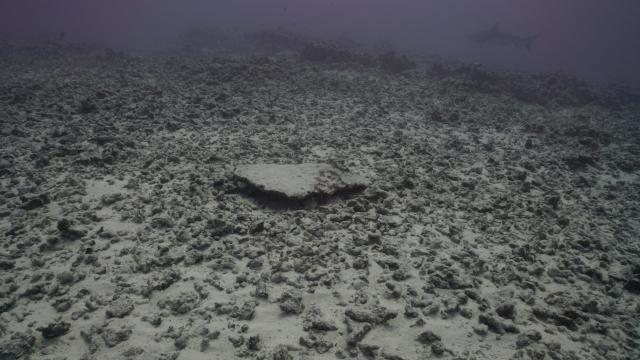

“We dropped down and at first I thought I was at the wrong spot because all I could see was rubble and sand,” Pascoe told Gizmodo.

She and her colleagues took photos of the devastation and resurfaced. Kosaki — who was on the boat — wondered if the group of researchers was reading the GPS correctly after he saw the divers’ photos.

But then they noticed an acoustic receiver below used by one of their colleagues to log tagged predatory fish that swim by. The corals were gone, but Rapture Reef’s receiver remained, embedded in the underwater wasteland like a grave marker.

“That was our confirmation,” Pascoe said. “Rapture Reef was demolished.”

She remembers what the reef was like when she first saw it in 2015 on a research cruise to Papah?naumoku?kea.

“It was one of the most beautiful sites,” Pascoe said. “Just tons and tons of fish, lots of schools of all different types. Lots of predators: uluas, monk seals, Galapagos sharks, whitetips. It was a very diverse ecosystem before the hurricane.

“Everything is dead. It looks like a parking lot now.”

Kosaki remembers when the reef was first named. In 2000, NOAA pushed to explore Papah?naumoku?kea from the perspective of conservation biology. Just by chance, one of the first spots Kosaki and his colleagues explored was Rapture Reef, which they unofficially named after their charter vessel, Rapture. He called it one of the most beautiful reefs he’s “ever seen in 35 years of diving in Hawai’i.”

But Rapture Reef was more than just eye candy. It, like other nearby atolls, was home to a uniquely high proportion of fish species found nowhere else on Earth. The Hawaiian Archipelago has distinctive coral reef ecosystems, the consequence of their physical isolation in the middle of the vast Pacific where they’ve evolved mostly out of the reach of Asian and American reefs.

As a result, about a quarter of the fish species are endemic to the islands, and this biodiversity quirk is even more pronounced in Papah?naumoku?kea. Rapture Reef was also one of the only places in Hawai`i where giant Acropora table corals grew in abundance.

The reef quickly became a revered and heavily-studied site among scientists working in Papah?naumoku?kea, with Kosaki calling it their “sentimental and aesthetic favourite.”

Rapture didn’t depart this world alone. The entire south side of the atoll seemed wiped clean by Walaka.

“[The reefs] were completely gone,” says Kosaki. “It must have been a frightening amount of energy that was unleashed on French Frigate Shoals.”

The team wanted to survey the Shoals’ north side, but the unnerving discovery of invasive algae mats elsewhere in Papah?naumoku?kea led to a strict quarantine for the ship’s return trip.

Kosaki thinks the reef will recover, in time. It’s been 10 months since the hurricane, and there are already some tiny, dime to quarter-sized corals growing on the loose, rubble remains of the old reef. But he’s concerned about the impact of increasing frequency and severity of storms in the region from climate change-driven ocean warming.

Corals have evolved alongside hurricanes for eons, he says, but last year was the most intense Pacific hurricane season on record, and the young corals at Rapture are very vulnerable to even a modest storm.

Kosaki said corals could have a harder time bouncing back from repeated storms because “you have a partial recovery and then you get hit again, and another partial recovery, and you get hit again.”

Despite the loss of Rapture Reef, the expedition was not without any good news. Lisianski Island is on the mend, and some important science will come out of monitoring Rapture Reef’s potential revival from the rubble. It’s this message of hope, that even catastrophic losses need not be permanent, that Kosaki wants to share.

“You’ve got to have hope,” he said. “Otherwise, you’d just throw your hands up and quit.”