Scientists have gained some insight into one of the first known calamities to visit mankind: a two century-long pandemic caused by the bacterial disease plague. Studying the remains of plague victims, the researchers say they were able to sequence the genomes of plague strains that devastated the Roman Empire starting in the 6th century. They also found direct evidence that plague’s destruction made it as far as to England.

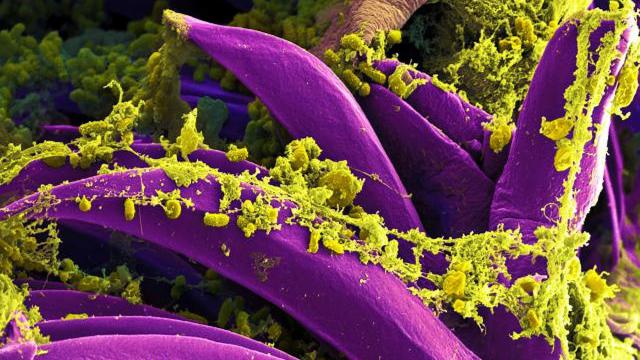

While now synonymous with pestilence and death, plague was first the specific name of a disease caused by the bacteria Yersinia pestis. Throughout humanity’s history, and especially since we started living in condensed cities and could travel far, plague has reared its ugly head and caused civilisation-shaping epidemics and pandemics. The earliest documented instance of this happening was the Plague of Justinian (it’s also been called the First Pandemic, though there were probably earlier pandemics involving typhoid and other diseases).

Beginning around mid-500 AD, the pandemic would earn its name from mostly afflicting the Eastern Roman Empire, right in the middle of Justinian the First’s reign. The pandemic, fuelled by recurrent waves of outbreaks spread by ship-riding rats whose fleas carried the bacteria, would outlive Justinian by more than a century, lasting until around 750. By then, it had killed off tens of millions of people—possibly as much as half of the world’s population—and helped destroy the Roman Empire.

But compared to the more famous and destructive Black Death—a pandemic in the Middle Ages also caused by plague—we know less about the bacteria behind the Plague of Justinian. It wasn’t until 2013, for instance, that we had concrete genetic evidence that plague bacteria really was the true cause of the pandemic.

New research, published Thursday in PNAS, seems to build on the 2013 study, even including one of its authors.

The researchers sifted through human remains from 21 archaeological sites in Austria, Britain, Germany, France, and Spain, ultimately finding and sequencing the genomes of eight plague strains. One of these strains was found in a single burial plot in the modern day area of Cambridgeshire, England, strongly suggesting that plague had made it to the British Isles during this time, as some earlier documentary evidence had indicated. They then compared these genomes against a collection of other ancient and modern day plague strains.

“The retrieval of genomes that span a wide geographic and temporal scope gives us the opportunity to assess Y. pestis’ microdiversity present in Europe during the First Pandemic,” the authors wrote.

According to the authors, the genomes suggest that there were several distinct but closely related strains that laid siege to humankind during the Plague of Justinian, with some strains even existing at the same time in the same place. They also found evidence that plague evolved into a less virulent version of itself by shedding certain genes towards the end of the pandemic. What makes this discovery interesting is that essentially the same thing would later happen during the Black Death, with those plague strains losing genes in the same general region. If true, this would be an example of convergent evolution, which is when two populations independently evolve similar features.

The research doesn’t quite answer all of the enduring questions people have about the Plague of Justinian, particularly its origins, though it does offer a strong hint.

“The lineage likely emerged in Central Asia several hundred years before the First Pandemic, but we interpret the current data as insufficient to resolve the origin of the Justinianic Plague as a human epidemic, before it was first reported in Egypt in 541 AD,” said co-lead author Marcel Keller, now a genomics researcher at the University of Tartu in Estonia, in a press release from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History (Keller was a PhD student at the institute during the study).

“However,” he added, “the fact that all genomes belong to the same lineage is indicative of a persistence of plague in Europe or the Mediterranean basin over this time period, instead of multiple reintroductions.”