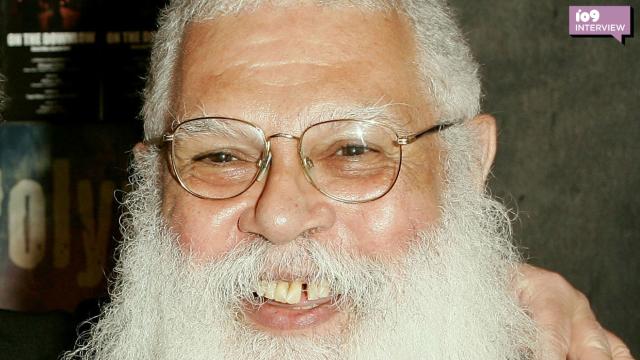

Writer Samuel R. Delany professes confusion at the kinds of titles his audience has sometimes attributed to him — in a Facebook post last year, he mentioned that some considered him a sort of Grand Marshall of Sci-Fi, and wondered what it meant.

For his readers, at least, that means he’s written scores of celebrated science fiction and fantasy books starting with his first published novel in 1962, The Jewels of Aptor, and including epics such as 1974’s Dhalgren. My first encounter with his work began with Aye, and Gomorrah, and other stories. The back of the 2003 anthology claims in a delightfully pulpy way that it’s “The ordinary stuff of ordinary fiction—but with a difference!”

The collection’s title tale explores gender identity, while “The Star Pit” deals with concepts of work, family, and breaking the limits of perception as a man encounters a young girl with the power to shift reality based on her emotions. And almost 10 years before Star Wars: A New Hope, a film Delany reviewed contemporaneously, he penned the short story “We, in Some Strange Power’s Employ, Move on a Rigorous Line,” a stunningly detailed tale of space travel and a clash on an alien planet.

Delany chronicled the writing of The Jewels of Aptor and his other early works in his 1988 memoir The Motion of Light in Water: Sex and Science Fiction Writing in the East Village. The book explores the author’s early years — he was born in 1942 — up to age 28, with much of its focus centered around the Harlem native living in the Village, married to a woman, but openly gay and having accepted affairs with men. In this day and age when queer and trans people are facing active erasure, the autobiography offers a reminder that histories and our elders are important.

“Something I’ve quoted a lot over the years is Thomas Mann on the worth of your own work,” Delany told io9, “‘I cannot know and you cannot tell me.’”

I visited Delany’s Fairmount, Philadelphia apartment with Alex Smith, my friend and sometime comics collaborator. Alex had his first published work as a writer in the tribute anthology Stories for Chip, “Chip” being Delany’s nickname. Delany lives his partner of many years, Dennis; the author chronicled a period in his partner’s life — when the then-homeless Dennis was selling books on the streets of Manhattan — in a graphic novel with Mia Wolff, Bread & Wine. Having just finished reading it myself, it was something of a strange pleasure to meet Delany and Dennis in real life instead of in Wolff’s ink drawings, albeit a few decades older than they appeared in the 1997 comic, with most of that story having taken place years before publication.

When asked about the making of The Motion of Light in Water, Delany replied, “[Jean] Cocteau’s advice: ‘What your friends criticise, cultivate.’ And one of the things people criticised me for was, whenever I wrote criticism, I was what a friend would call ‘promiscuously autobiographical.’ So I thought, well, I better cultivate it.”

Alex wondered about the resistance to the autobiographical style. “I think it was a holdover from the New Criticism, which was a brand of criticism where you were supposed to only deal with the text […] And yet, all the criticism I like is full of gossip!” Delany laughed. And on the literary value in anecdotal criticism, Delany added, “It brings the landscape and the life of the writer alive.”

“Other memories cluster loosely at that autumn,” he writes in The Motion of Light in Water, “the associational bonds connecting them as uncertain as the weather, as insubstantial as a momentary play of light in yellow leaves.”

In Delany’s book About Writing, he brings up the German term “Begeisterung,” or be-spiritness as he describes it. When I asked him about it, he said that you have to have the energy to see yourself through a project. “On several occasions I’ve gotten a few hundred pages into a project, [I’ve realised] ‘I thought I knew where this was going.’” When asked about the life of a writer, Delany replied, “I’ve never tried to keep a schedule, I’ve never tried to make sure I write a certain amount every day. I have a project and I work on it as best I can […] I’ve always been dyslexic, all my life, and I used to tell my Temple students, ‘I don’t write, I rewrite.’”

“I want to write a novel I’d like to read,” he added. “I write the novel I can’t find in my own library or on bookstore shelves.” He mentioned his admiration for Gengoroh Tagame’s manga My Brother’s Husband, the story of two gay men and their child, and revealed that a graphic novel version of his own science fiction novel Babel-17, the story of a Chinese poet travelling through space to decode an enemy force’s language, is being developed.

At one point, Delany quit sci-fi for a number of years after “looking at the amount of money I was making,” instead devoting himself to music with the group Heavenly Breakfast around 1968. They had planned to record one day, in fact, but when they got to the studio they found a chain on the door. “Con Edison had changed their policy […] there were only eight little recording studios that could have done us, and they all went out of business the same weekend. And they were studios that put out a lot of interesting music — Lovin’ Spoonful, the people that were doing experimental stuff that occasionally took off and really made it big […] then that happened, and that was just before the King assassination […] So I decided, OK, let’s go back to writing.”

When I mentioned that both Alex and I had played in bands before as well, Delany said, “Really smart people have different talents and they want to explore them all, and you settle on writing because it’s the cheapest to pursue.”

Alex asked about another period, this time in the ‘80s, when Delany also quit pursuing sci-fi. Delany told us a publisher wanted a sequel to his sci-fi novel Stars in My Pocket Like Grains of Sand, a story about shifting cultural, racial, and sexual perceptions. “It was AIDS plus an eight-year-relationship breaking up that was fuelling much of Stars in My Pocket, and so the sequel never got done. And then somebody said, ‘You wrote a sequel anyway, it was called The Mad Man, it just wasn’t a science fiction novel.’”

Alex also wondered about how the impact of AIDS informed Stars, and how Delany felt about writing sexuality after the book. “It became very apparent to a lot of people who were pursuing public sex, you had to be very honest, and very explicit,” Delany said.

“Very honest, and very explicit” describes the ethos of a number of Delany’s books, from the infamous novel Hogg, to the hand-drawn gay sex scenes in Bread & Wine, to The Motion of Light in Water’s descriptions of queer cruising in New York in the ‘60s in the years leading up to the Stonewall Riots. The author described how the news media greatly underestimated the numbers gathered at a police raid that took place upon a popular dock for cruising—while Delany observed at least a hundred men gathered there for sex, the papers reported just a few. In my mind, he was pointing out how words, language, and truth can be all we have.

He writes: “‘History’ (as one evokes it in biography, in autobiography) is what most of us do not remember, what most of us cannot speak of.”

Annie Mok is an author-illustrator and musician based in Philadelphia.