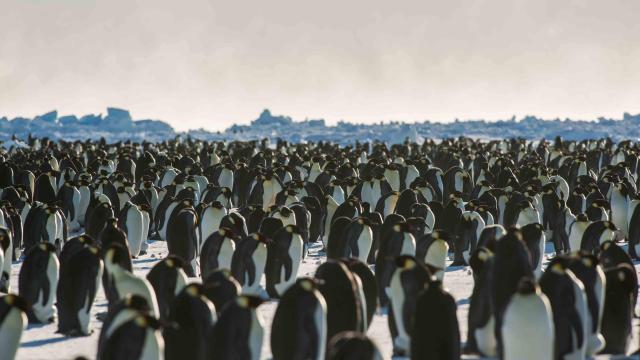

One of Antarctica’s largest emperor penguin colonies is all but gone following three unprecedented years in which the penguins weren’t able to raise chicks.

A new paper published today in Antarctic Science describes the disappearance and likely relocation of the Halley Bay emperor penguin colony—one of the largest colonies in Antarctica in terms of population, and second only to the Coulman Island colony in the Ross Sea.

British Antarctic Survey researchers Peter Fretwell and Philip Trathan used satellite imagery to document three consecutive years, from 2016 to 2018, in which the Halley Bay penguins suffered almost total breeding failure on the Brunt Ice Shelf.

This “prolonged period of failure,” the authors wrote in the study, is “unprecedented in the historical record.” The researchers attributed the penguins’ inability to raise chicks to unstable sea ice—the result of turbulent environmental conditions caused by the unusually strong El Niño of 2015, among other factors. Encouragingly, however, many of the Halley Bay emperor penguins appear to have joined a nearby colony, but the authors warn that the episode is sneak preview of things to come on account of human-induced climate change.

The preferred breeding ground of the Halley Bay emperor penguins is at the northern side of a small inlet known as Windy Creek along the Weddell Sea. This population has been sporadically studied since 1956, with population sizes fluctuating between around 14,300 and 23,000 breeding pairs — around 6.5 to 8.5 per cent of the total global emperor penguin population.

From this location, the penguins forage in the shallow waters at the nearby McDonald Bank and the McDonald Ice Rumples. Usually, this area is able to retain stable sea ice until December, and it sometimes lasts all summer long. The chicks raised at this site typically fledge between mid-December and early January.

“Although the recorded population has varied, the colony is consistently the largest in the Weddell Sea, over twice the size of any other colony in the region,” Fretwell and Trathan wrote in the study. “There have been no previously recorded instances of total breeding failure at the site.”

But that’s now changed.

High-resolution imagery captured by the WorldView2 and WorldView3 satellites showed near-complete reproductive failure in 2016, followed by similarly fruitless breeding campaigns in 2017 and 2018. Disturbing images taken of Windy Creek demonstrate the effects: The once smooth, guano-smeared ice has been replaced by a jagged, poop-free landscape — save for a painfully small pocket of penguins persisting in one corner.

As noted in the study, the catastrophic breeding failure was linked to the early breakup of ice in the areas used for breeding—a breakup triggered by “a particularly stormy period in September 2015, which corresponded with the strongest El Niño in over 60 years, strong winds, and a record low sea-ice year locally.” Conditions at the site have not recovered since that time.

The event could not be conclusively linked to human-induced climate change, but as Trathan pointed out in a press release, current climate models suggest emperor penguin populations could drop between 50 to 70 per cent by the end of the century as sea ice conditions change.

In an email to Gizmodo, Fretwell added further colour to the issue, saying El Niño is one possible driver of the local loss of ice, and though technically speaking this is not climate change, he believes El Niño events will become more pronounced in the coming years.

“Whether an individual event like this was driven by larger climate change is impossible to say,” Fretwell told Gizmodo. “What we can say is that over the next century, all our models suggest that many emperor penguin colonies will face similar problems — this study is the first to show how emperor penguins react to these environmental challenges.”

Indeed, while the Halley Bay emperor penguin colony is now practically gone, the nearby Dawson-Lambton colony, some 55 kilometers to the south, has increased significantly in size. It’s now 10 times larger than it was prior to the breeding collapse at Windy Creek. It’s potent evidence that Halley Bay penguins have found a new place to roost—an encouraging sign that the penguins are adaptable and resilient in the face of environmental change.

Heather Lynch, a statistical ecologist from the Department of Ecology and Evolution at Stony Brook University, said the new finding is a bit of a mixed bag.

“On the one hand, it’s obviously concerning that one of Antarctica’s largest emperor penguin colonies has been experiencing repeated breeding failures and has been largely abandoned,” wrote Lynch, who wasn’t involved with the new study, in an email to Gizmodo.

“On the other hand, the fact that many — if not all — of these emperor penguins appear to have relocated to another nearby colony is reassuring, as it highlights that emperors are more mobile and less site faithful than we had once believed.”

That said, Fretwell is concerned about some aspects of the Dawson-Lambton site. The penguins are now further from the shallow banks where they likely forage, and the Halley Bay penguins are now in direct competition with the penguins already present at this site. But “it’s better to be a slightly less favourable site than one that is totally untenable,” said Fretwell.

For the authors of the new study, this finding drives home two primary messages.

“Firstly, that we have seen that emperor penguins, when faced with a total loss of sea ice, will move to find a better location—this is the first time we have seen this,” said Fretwell. “The second thing is that we really need a better understanding of what drives the shifts in the environment around these sites. Our knowledge of what drives sea ice conditions is really quite poor and if we are to understand how emperor penguins will fare with future climatic warming we must first understand what drives the changes in the sea ice.”

Lynch said the silver lining of the new study was the demonstration of how satellites can actually track these kinds of events, which, in the past, would’ve likely gone entirely unnoticed.

“But now we can get a better handle on whether these kinds of events are par for the course for an emperor penguin colony or something truly unusual with potential long term consequences for the species,” she said.