The appearance of moralizing gods in religion occurred after—and not before—the emergence of large, complex societies, according to new research. This finding upturns conventional thinking on the matter, in which moralizing gods are typically cited as a prerequisite for social complexity.

Gods who punish people for their anti-social indiscretions appeared in religions after the emergence and expansion of large, complex societies, according to new research published today in Nature. The finding suggests religions with moralizing gods, or prosocial religions, were not a necessary requirement for the evolution of social complexity. It was only until the emergence of diverse, multi-ethnic empires with populations exceeding a million people that moralizing gods began to appear — a change to religious beliefs that likely worked to ensure social cohesion.

Belief in vengeful gods who punish populations for their indiscretions, such as failing to perform a ritual sacrifice or an angry thunderbolt response to a direct insult, are endemic in human history (what the researchers call “broad supernatural punishment”). It’s much rarer for religions, however, to involve deities who enforce moral codes and punish followers for failing to act in a prosocial manner.

It’s not entirely clear why prosocial religions emerged, but the “moralizing high gods” hypothesis is often invoked as an explanation. Belief in a moralizing supernatural force, the argument goes, was culturally necessary to foster cooperation among strangers in large, complex societies.

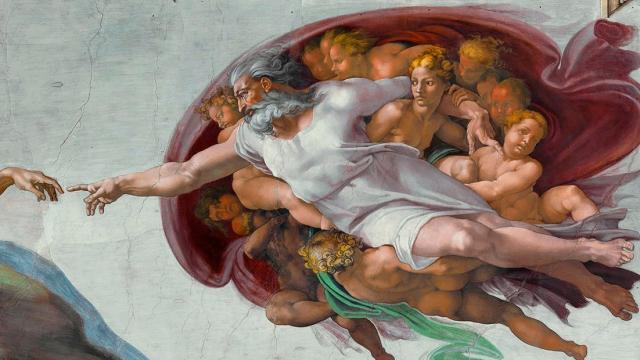

Indeed, various religions over the past several millennia have witnessed the emergence of prosocial religions, including the moralizing Abrahamic God and the Buddhist belief in karma. While religions satisfy a number of needs, such as offering existential meaning and comfort, they also serve as social control mechanisms. In the case of prosocial religions, it has been argued that an intimate and essential connection exists between complex societies and belief in a moralizing god—a connection the new research now throws into question.

The new research, led by Peter Turchin from the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Connecticut, was an effort to understand this apparent relationship more scientifically. To date, most studies on the matter have relied on psychological experiments or cross-cultural comparative analysis, rather than on historical data. The new study was an effort to overcome this shortcoming.

To that end, Turchin and his colleagues analysed historical data pertaining to social structures, religious norms, moral beliefs, and a plethora of other factors for hundreds of societies across the history of the world. A large database containing carefully curated historical, archaeological, and anthropological information was used for the study. This database, called Seshat: Global History Databank, was established in 2011 by Turchin, along with Oxford University colleagues Harvey Whitehouse and Pieter Francois, both of whom contributed to the new study.

The Seshat database, named in honour of the Egyptian goddess of knowledge and record keeping, is an ongoing project for tracking important historical and sociological changes over time. The project is meant to foster data-driven research and prevent biases from creeping into analyses—a common problem in historiographical research.

For the new study, Turchin and his colleagues analysed nearly 50,000 records spanning the last 10,000 years of world history—from the Neolithic to the beginning of industrial/colonial periods. Over 400 different societies were included from 30 regions around the globe. In all, 51 different measures of social complexity and four measures of moral divinity were used to assess any potential connection between the two. Measures of social complexity included population, size of the military, and the presence of roads, judicial system, and scientific texts. Moralizing gods were identified by beliefs such as a high god who created the Universe and actively enforces human morality.

“It’s true that some researchers use more sophisticated measurements involving things like performing experiments to measure degrees of belief in moralizing gods, but these can only be done for contemporary societies,” noted the researchers in a press release. “We can’t go back to ancient Egypt and ask the people how much they believe in Maat’s power to punish their misdeeds in the afterlife.”

Importantly, the researchers controlled for past historical relationships, such as the spread of Christianity and Buddhism, among the societies studied to ensure the results were consistent across the various regions analysed.

Analysis of the Seshat data showed that belief in moralizing gods appeared after — and not before — the rise of social complexity. Gods “who care about whether we are good or bad arose too late to have driven the initial rise of civilizations,” said the researchers in a press release. And when these beliefs did appear, they occurred in so-called megasocieties, that is, societies with more than a million people.

“This suggests that, even if moralizing gods do not cause the evolution of complex societies, they may represent a cultural adaptation that is necessary to maintain cooperation in such societies once they have exceeded a certain size, perhaps owing to the need to subject diverse populations in multi-ethnic empires to a common higher-level power,” the authors noted in the study.

So without the presence of vengeful moralizing gods to keep citizens of complex societies in check, it’s reasonable to wonder how these societies managed to stay intact. One possibility detected by the researchers is that daily or weekly collective rituals — the equivalent of Sunday mass or Friday prayers — appeared early in the rise of social complexity.

Such rituals, they said, “may have allowed new beliefs and practices to spread to, and become stabilised within, much larger populations than had previously been possible.” But once the threshold of a megasociety was surpassed, the cohesion produced by these rituals wasn’t enough to keep things civil.

A possible oversight of the new paper is the possibility that moralizing gods did in fact trigger the initial expansion of complexity — it’s just that this data doesn’t exist, as some of these early societies did not keep written records. The researchers admitted this is a distinct possibility, but “the fact that written records preceded the development of moralizing gods in 9 out of the 12 regions analysed (by an average period of 400 years) — combined with the fact that evidence for moralizing gods is lacking in the majority of non-literate societies — suggests that such beliefs were not widespread before the invention of writing,” explained the authors in the study.

Ahmed Skali, a researcher in the Department of Economics, Finance and Marketing at RMIT University in Australia, described the new paper as “fascinating,” saying it “highlights the enormous progress the scientific community has made in understanding why and how we have come to have the societies we have today.” He admitted to being surprised by the results.

“My best reading of the available evidence, up to this study, was that moralizing gods emerged first, then societies used them to enforce cooperation,” Skali told Gizmodo. “But this is why empirical science is so exciting, and such carefully designed studies as this one really help shift our understanding of the world we live in.”

Skali said the claim that multi-ethnic empires can be sustained by prosocial religions makes a lot of sense, pointing to the two Islamic Caliphates in place from the 7th to the 16th century and the Ottoman Empire, among others. He also found it interesting that writing tended to emerge before the appearance of moralizing gods. Skali speculated that it’s much easier for the concept of moralizing gods to spread once the technology allows it, similar to how the Protestant Reformation spread through printing in Europe in the 16th century.

Finally, and very importantly, the study suggests people didn’t behave morally out of a fear of facing eternal hell fire from a moralizing god.

“Instead, there is some evidence to suggest that routine rituals help bind people together,” said Skali. “That is a fascinating finding.”

[Nature]