There are as many valid criticisms of Peter Farrelly’s Best Picture Oscar-winner Green Book as there are listings in Victor Hugo Green’s The Negro Motorist Green Book. But an upcoming adaptation has a lot more potential to tell the real story, even if there are Lovecraftian monsters involved.

The Negro Motorist Green Book (published from 1936 to 1966) was a guide to the places black people driving across the Jim Crow-era U.S. could stop to rest and replenish themselves without fear of being denied service by businesses, driven out of town by racists, or murdered.

With the growth of interstate highways came the promise that Americans could more easily travel long distances and experience more of the country. But that same promise was not afforded to black and other non-white drivers who faced the risk of being caught in sundown towns, places where white members of the local community — including law enforcement officials, in some cases — would not hesitate to kill them should they be seen within city limits.

Though the specters of Jim Crow and segregations are things most often associated with the South, sundown towns proliferated throughout the U.S., meaning that black drivers had no choice but to be strategic in their travels so as never to be caught after dark in a place where their lives might be very much in danger. Green’s book was an invaluable asset for black travellers at all points along their journeys. Each trip planned with the help of The Negro Motorist Green Book is a story about black Americans collaborating in order to persevere and thrive in a land that did not love us, and because that continues to be true of the country, it’s easy to understand why the book is an important part of our history and why folks would want to create stories around it.

The problem with the recent Peter Farrelly-directed Green Book film is that it ignores the cultural significance of Green’s book and doesn’t even center it as the heart of its story.

In Farrelly’s take — written by Nick Vallelonga and Brian Hayes Currie—Don Shirley (Mahershala Ali) is a gifted black musician who hires Tony Vallelonga (Viggo Mortensen), an Italian bouncer, to work as his driver during an upcoming tour throughout the U.S. that’ll take them from the Midwest into the Deep South. Through the power of road tripping, the unlikely pair become friends as substantive interrogations about race or the men’s inner lives are passed over in favour of scenes about how everybody likes fried chicken and good music.

Green Book is, put simply, another story about racism that’s much more concerned with making white people feel good about sitting through a movie about racism, in which a white person resists the urge to be egregiously racist because their one black friend told them to. Even setting aside all the issues of Green Book’s historical accuracy and alleged disrespect to Shirley’s family, the film’s utter lack of regard for The Negro Motorist Green Book makes it difficult to see it as a story that truly understands the cultural factors in play that made its existence possible.

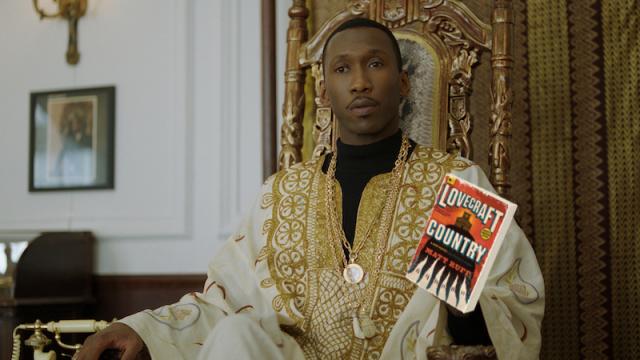

The Negro Motorist Green Book deserves a telling of its tales that both respects what the book meant and can speak to the large audience that can and should know more about its importance. Where Green Book failed, HBO’s upcoming adaptation of can and should succeed in ways that are readily apparent the moment you begin reading the book.

Atticus Turner, one of Lovecraft Country’s central heroes, is a young, science fiction-loving black veteran recently back from time in the Korean War. He soon realises that his service to his country doesn’t actually mean all that much back home because of the colour of his skin. While Atticus’ family and friends love him dearly, the racist micro and macro-aggressions he faces on a daily basis are a constant reminder of what it means to be black in America. Racism is a demon all of Lovecraft Country’s characters must face, but they there are also actual demons out there in the world they cross paths with, and its when these literal and metaphorical evils intersect that Lovecraft Country begins to really shine.

When Atticus’ father Montrose goes missing, leaving only instructions for Atticus to come looking for him in the fictional (and very Lovecraftian) town of Ardam, Massachusetts, he sets out to find him with the help of his uncle George, who runs the Safe Negro Travel Company, and his friend Letitia Dandridge, a devout Christian. Together, the trio uses George’s knowledge of safe zones to make their way from Chicago to Massachusetts, and as they journey they encounter all manner of supernatural beings—both very literal monsters and embodiments of the horrors that The Negro Motorist Green Book was designed to help people avoid. Here’s an excerpt:

George had begun publishing The Safe Negro Travel Guide as a means of advertising his travel agency’s services, and though the Guide had ultimately become profitable in its own right, the agency—now expanded to three locations—remained his primary business and source of income. The agency would book trips and tickets for anyone, but specialised in helping middle-class Negroes negotiate with a travel industry that was at best reluctant to accept their patronage.

Through his network of contacts and scouts, George kept up-to-date files not only on which hotels allowed Negro guests, but which air and cruise lines were most likely to honour their reservations. For those wishing to vacation abroad, the agency could recommend destinations that were relatively free of local race prejudice and, just as important, not overrun by white American tourists—for nothing was more frustrating than travelling thousands of miles only to encounter the same bigots you dealt with every day at home.

The power that the Ku Klux Klan’s grand wizards have lies in the reach of their organisation’s networks and their ability to enforce their hateful ideology through coordinated violence. Lovecraft Country imagines a world in which that’s still very true, but the wizards also happen to be actual wizards of a sort, something that Atticus and company can barely wrap their minds around as the story unfolds.

Lovecraft Country shifts between focusing on its allegorical monsters and its human ones with a deftness that’s just shy of letting you assume it’s a work of pure magical realism. It wants you to understand that the racist ghost and the shady realtor who purposefully sold the house it haunts to black owners are both real problems the book’s characters have to face. Like a carefully crafted highway system, Lovecraft Country’s larger plot is made up of a handful of intersecting stories that all feed back into one another, reminding you of what’s keeping its heroes safe: their togetherness, their adaptiveness, and the knowledge afforded to them by their guide book and the wisdom it holds.

With Jordan Peele and J.J. Abrams producing, and Underground’s Misha Green attached as showrunner, there are any number of directions HBO’s adaptation of Lovecraft Country could take. So long as it honours the source material, and bears in mind the larger cultural significance of the stories it’s telling, it’s likely to do The Negro Motorist Green Book’s legacy justice in a way Green Book never could.