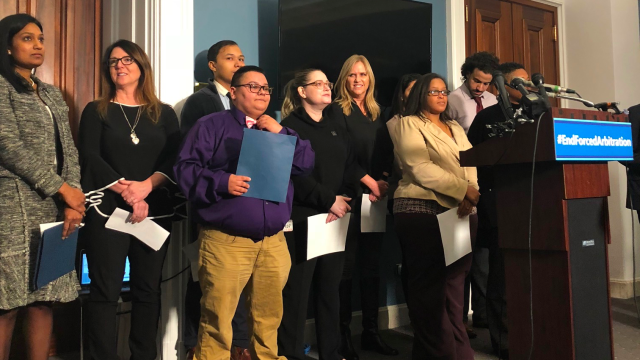

In a bustling room inside the U.S. Capitol on Thursday afternoon, a group of survivors wearing black pins stand behind a podium that reads #EndForcedArbitration. They are all waiting to share their stories — of sexual harassment, of sexual assault, of racial discrimination, of unfair labour practices, of consumer exploitation. The common thread connecting these disjointed individuals is that they have all been silenced, forced to settle their disputes behind closed doors. Forced to waive their right to have their day in court.

“I stand before you joined by workers from all backgrounds, as well as assault and harassment survivors, consumers who’ve had money illegally stolen from them, families who can’t get justice for their loved one in a nursing home, and a Navy reservist who was fired for taking time off to serve his country,” Tanuja Gupta, a program manager at Google and one of the organisers of the Google walkout, said during the press conference on Thursday.

Google announced just last week that it was eliminating forced arbitration for all employees. Gupta, who now helps lead efforts to end forced arbitration, joined five other Google employees for the trip to D.C. this week to bolster efforts to end forced arbitration across the United States.

Thursday’s press conference centered on the introduction of the Forced Arbitration Injustice Repeal Act (FAIR Act), which would prohibit forced arbitration agreements for both employees and contractors as well as agreements that prevent individuals from seeking class-action lawsuits.

When you sign a contract with a forced arbitration clause, you are waiving your right to have your case heard by a trial by jury. You are also giving up your right to an appeal and, oftentimes, to pursue a class-action lawsuit. Instead, your case is heard by an outside party, an arbitrator, who settles the dispute privately. According to a 2017 study from the Employee Rights Advocacy Institute for Law & Policy, of the 100 largest companies in the country, 80 per cent settled an employment dispute through arbitration since 2010. Of those companies, half of them were settled through forced arbitration.

Critics have increasingly called out Silicon Valley companies’ use of forced arbitration in recent years, which has resulted in collective action that pushed some of these companies to adopt fairer labour practices. In December 2017, Microsoft became the first to announce that it was eliminating mandatory arbitration for sexual harassment claims. Uber, Google, Facebook, eBay, and Airbnb followed suit.

Initially, many of these companies only waived these clauses for sexual harassment claims. Employees facing racial discrimination in the workplace still weren’t able to have their case heard by a jury. Further, these changes didn’t extend to contractors—a massive component of the tech industry’s workforce—or those who wanted to pursue a class-action lawsuit. The FAIR Act would eradicate the unfair labour practice not just for some, but for all—employees, contractors, and consumers.

“We watched as some companies tried to create policies in a surgical fashion, carving only a narrow category of cases where justice might be received,” Gupta said to the crowd gathered in D.C. “But workers continued to beat the drum of intersectionality and highlight the root cause of all inequity: the structural imbalances of power. And slowly, some companies started to relent, rolling out blanket policies that eliminated forced arbitration.”

Michael Subit, an attorney who specialises in employee discrimination and harassment cases, told Gizmodo in November of last year after Google only waived forced arbitration for sexual harassment claims that when companies fail to eliminate the agreements for all forms of misconduct, they are conveying that they “are not doing it for the reasons they are saying, they’re simply doing it because they’re afraid of the backlash.” And for individuals with multiple claims — such as a woman of colour who experienced both sexual harassment and racial discrimination—they would have to bring a case in arbitration and another in litigation. “From a perspective of efficiency,” Subit said, “this is no way to run a railroad.”

The survivors at the press conference illustrated the range of ways that being forced into arbitration took away their rights. This included Gretchen Carlson, who filed a sexual harassment lawsuit against then-Fox News Chairman Roger Ailes in 2016. Carlson told the crowd that many survivors had come forward to share their experiences of pain and shame with her, “but what they’ve really shared with me is how they were silenced,” she said. “You see, arbitration is the harassers best friend because it silences all of the victims.”

Carlson was joined by Kelly, a woman from Kentucky, who said that her mother, a union leader who fought for the rights of teachers, was “severely mistreated” at a nursing home. When Kelly tried to hold the nursing home accountable, she was forced into arbitration.

Richard and Levi, from New York and Ohio respectively, were both workers at Chipotle. They claimed that Chipotle automatically clocked them out and made them continue working without pay. When Richard complained, he says, he was fired. Levi described it as being “treated like a robot.” Both former employees say they were forced into arbitration to settle their disputes with the company.

Lily from California said that she was sexually assaulted by a Massage Envy massage therapist. She brought a lawsuit against the company. For a year and a half following her assault, she tried to cancel her membership with the company, eventually deciding to download the Massage Envy app to cancel it there. There was a forced arbitration clause in the app’s terms of service agreement, and now the company is trying to force Lily into arbitration. “I didn’t want to be a victim, she said. “Forced arbitration is trying to take away my rights.”

Neither Chipotle nor Massage Envy immediately responded to a request for comment.

Glenda and Peter Perez, a married couple from Florida, used to both work for the same company. Glenda said that when she reported racial discrimination two years ago, she was fired and forced into arbitration. Her husband Peter later claimed that he saw a photo of the arbitrator “cozied up” with the attorney for their employer at a party. When he complained, he was also fired.

“We are counting on you,” Glenda, visibly choked-up, told the crowd.

Each of the survivors wore square black-and-white pins reminiscent of the Time’s Up pins donned on the Golden Globes red carpet last year, a gesture to call attention to the movement that served as a response to the flood of sexual harassment and assault allegations in Hollywood and a push for racial and gender equality within the entertainment industry.

Gupta told me she sees the fight as bigger than just a fine-print dispute, comparing it to the private prison system—a cheaper and faster method that benefits corporations but ultimately erodes civil rights. It’s a fight that’s essential for eliminating systemic discrimination and harassment in the workplace. It’s not just about affording survivors the opportunity to have their day in court. It’s about ending the cycle of corporate power that allows companies to keep the wrongdoings of a perpetrator quiet.

“It is 2019,” Gupta said as she closed out her speech. “Time is up.”