A 52-million-year-old fossil found in Wyoming is now the earliest known seed-eating perching bird in the scientific record, a discovery that’s shedding new light on the history and early eating habits of these now-ubiquitous birds.

Perching birds like crows, finches, sparrows, and robins are prolific, accounting for more than half of all bird species alive today. Also known as passerines, these birds are distinguished by the arrangement of their toes, in which three point forward and one points back — an orientation that, as the name suggests, is amenable to perching.

Despite their current diversity, however, passerine fossils are scarce, hindering scientists’ understanding of how and when they evolved. The recent discovery of two ancient passerine fossils, one in Wyoming and one in Germany, represents an important contribution in this area.

The Wyoming specimen is particularly noteworthy owing to its age. Found within the Green River Formation near Fossil Lake, this seed-eating perching bird lived 52 million years ago during the Early Eocene. The German bird, a passerine belonging to the same species, also lived during the Eocene, some 47 million years ago.

The associated study, published today in Current Biology, describes these species as “the oldest fossil birds to exhibit a finch-like beak and provide the earliest evidence for a diet focused on small, hard seeds.”

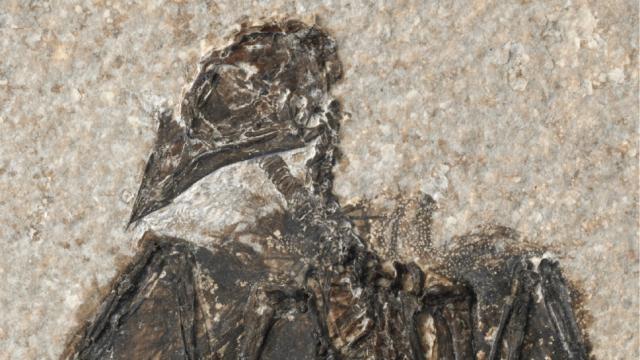

Fossil Lake is renowned for both the diversity of its fossils and their quality. The Wyoming specimen is no exception, preserving fine details of this ancient creature in crisp relief.

“Yes, it is a beautiful fossil,” Daniel Ksepka, the lead author of the new study and curator at the Bruce Museum in Connecticut, told Gizmodo. “The fossils were formed at the bottom of a lake. The bottom waters appear to have been depleted in oxygen, so no scavengers could survive there.

Thus, any carcasses that sank to the bottom would not be disturbed. Rivers and streams emptying into the lake were saturated with the mineral calcium carbonate, which caused a lime ooze to slowly rain down, covering the remains. Over time, this hardened into limestone, preserving the bones within for millions of years.”

Ksepka and his colleagues named the new species Eofringillirostrum boudreauxi (pronounced ee-oh-frindz-oh-rah-strum bo-dree-oh-shee), the first part meaning “dawn finch beak” and the latter part in honour of long-time Field Museum supporters Terry and Gail Boudreaux. Eofringillirostrum is now the earliest fossil showing a bird with a finch-like beak, resembling those found in modern sparrows and finches.

Older passerines have been discovered before, including 55-million-year-old fossils found in Australia, but those earlier versions weren’t capable of eating seeds, munching instead of fish and insects.

Eofringillirostrum were about the size of a red-breasted nuthatch—a fairly common species spotted at bird feeders in the U.S. Northeast.

“Its beak was very finch-like, extremely similar to species like the American goldfinch for example—short, conical, and tapering to a sharp point,” said Ksepka. “The big difference from modern passerines was that it had a reversed fourth toe. The fourth toe pointed backwards, perhaps aiding in grasping or clinging. In modern songbirds, the fourth toe points in the same direction as the other toes. The beak shape suggests it ate small seeds.”

Eofringillirostrum lived in a subtropical environment, surrounded by small primitive horses, early bats, and boa-like snakes. Back then, Fossil Lake was filled with herring-like fish, gars, and even freshwater stingrays.

The German specimen, another Eofringillirostrum, lived far away, showing these birds had spread out geographically around 47 million years ago. That said, the paucity of fossils suggests they were relatively few in number.

The new research also suggests that the avian ability to eat hard seeds is a relatively recent evolutionary phenomenon. Importantly however, while early passerines evolved many different beak shapes, none of these species left any descendants that survived to the present day.

“I think the biggest revelation from these new fossils is that we know know that early passerines very quickly evolved beak shapes to eat all types of food like seeds, insects, and nectar,” said Ksepka. “Then, these early species all died out and their roles were taken over by more modern species. It basically means that todays perching birds actually ‘re-invented the beak,’ re-evolving many of the beak types that were lost when those early species died out.”

At any rate, we know that a diversity of beak types were in place by the time of the Early Eocene, including the finch-like beaks of very early passerines. As always, the discovery of more fossils will shed even more light on this important period of avian evolution.