With the ban on the international trade of ivory, dealers are increasingly turning to a surprisingly abundant alternative: the tusks of woolly mammoths preserved in Siberian permafrost. But at what cost?

A new AFP report is highlighting the burgeoning trade in woolly mammoth tusks — a development that, through the most optimistic lens, could ease pressure on living elephants, result in new paleontological discoveries, and provide new job opportunities for people living in a remote region of northern Siberia. On the dark side, the prospecting of woolly mammoth tusks could damage sensitive permafrost regions and further perpetuate the demand for ivory.

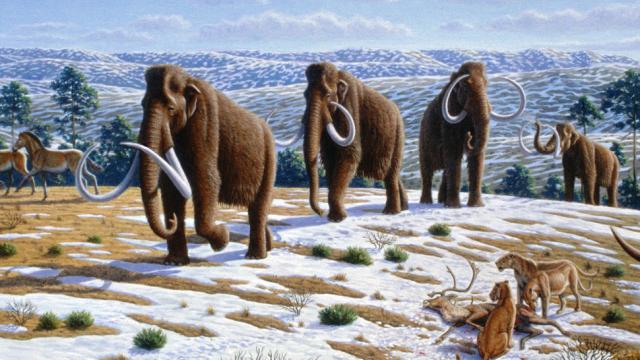

This “mammoth rush,” as one collector described it to the AFP, is happening primarily in Yakutia, a northern area of Siberia that’s about five times the size of France. According to the AFP, this region is absolutely littered with the remains of woolly mammoths, a species that went extinct around 4,000 years ago. During the Pleistocene, Yakutia, which borders the Arctic Ocean, was home to an untold number of woolly mammoths, who dominated the landscape for thousands of years. Today, Yakutia is covered in permafrost, and the frozen remains of these once-majestic creatures can often be found sticking out from the surface.

China banned the import and sale of ivory at the end of 2017, prompting traders to turn to the remains of mammoths, a tusked mammal and a distant relative of modern elephants. In Russia, all that’s needed to prospect and trade woolly mammoth ivory is a permit, and the practice isn’t fully regulated. What’s more, woolly mammoths aren’t protected by international agreements on endangered species because, well, they’re not endangered—they’re extinct.

According to the AFP, Russia exported nearly 80 tons of “ice ivory,” as the mammoth tusks are called, in 2017, of which 80 per cent went to China, where ivory is typically carved and turned into sculptures and trinkets. High-quality mammoth ivory can sell in China for over $1,425 per kilogram, or $3,134 per pound, so it’s a lucrative business, the AFP reports — and an estimated 550,000 tons of mammoth tusks are buried in Yakutia. If true, this equates to $3 trillion worth of ivory. By comparison, the oil sands in Alberta, Canada, are worth $2 trillion. Though to be fair, a glut of ivory in the market would send prices plummeting.

Mammoth ivory is already making its way into the market and, by consequence, illegal retail items. Researchers at the WildGenes laboratory of the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland recently discovered traces of mammoth DNA in ivory trinkets sold illegally in Cambodia. Geneticist Alex Ball, who led the research, told the BBC that the ivory basically came “from the Arctic tundra, dug out of the ground,” adding that the “shop owners are calling it elephant ivory but we’ve found out it’s actually mammoth.”

Traditionally, local hunters and fishermen would stumble upon the remains of woolly mammoths, but now, given its value, this happenstance activity is becoming a viable profession on its own. Locals see it as the only viable way to earn a living in an area where jobs are scarce and agriculture is impossible, the AFP reports. Most prospectors simply scour the landscape in search of mammoth bones; the use of water jets to dislodge mammoth remains from mounds or the sides of cliffs is prohibited by Yakutia law.

As noted, this prospecting activity isn’t regulated, and it sits in a kind of grey area. Consequently, prospectors and traders are subject to what they perceive as unfair confiscations by state officials, which happens frequently, according to the AFP, despite collectors having the required permits. A Russian bill to regulate this trade has remained idle since it was first proposed in 2013, but it could finally pass this year.

As AFP writer Maria Antonova reports, some scientists are actually ok with the prospecting of mammoth remains:

Valery Plotnikov, a paleontologist at the Yakutia Academy of Sciences, said that the mammoth rush had been beneficial to science by providing specimens that the academy could not otherwise afford.

He was studying a rare prehistoric cave lion cub that a collector found last summer.

“We have a symbiosis with licensed collectors,” he said, adding that they provide researchers with valuable items for free but remain owners of specimens and stand to profit when their finds are exhibited abroad.

This mammoth rush, it’s fair to say, comes with its pros and cons.

Sure, it could result in some new paleontological discoveries, and a case can be made that it’s lowering demand for ivory from living elephants, but there are some negative consequences to consider. First, the prospecting and proliferation of ivory into the market can only serve to perpetuate the cultural demand for the substance even further, putting living elephants in peril of poaching. Second, the mammoth rush could conceivably result in more intense prospecting in Yakutia, resulting in mining operations and other environmentally damaging activities.

The Russian government, as it prepares to regulate this industry, must weigh all these issues very carefully.