It’s often true that broad groups of people can experience a disease differently. African Americans, for instance, seem to be more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease than their white counterparts in the U.S. A new study published Monday in JAMA Neurology offers clues to why that’s the case. It found that African Americans have lower levels of a biomarker of the disease, but only if they carry a specific genetic variation.

This subtle distinction, the researchers suggest, could hamper attempts to accurately diagnose and study the devastating neurological condition in African Americans. And it could also indicate that the underlying roots of the disease can vary between different populations.

Researchers from the Washington University School of Medicine looked at the spinal fluid and brain scans of more than 1,200 volunteers. Of these volunteers, 173 were African Americans. The elderly volunteers (their average age was 70) had taken part in various long-term studies conducted at the university’s Knight Alzheimer Disease Research Center (ADRC) between 2004 to 2015.

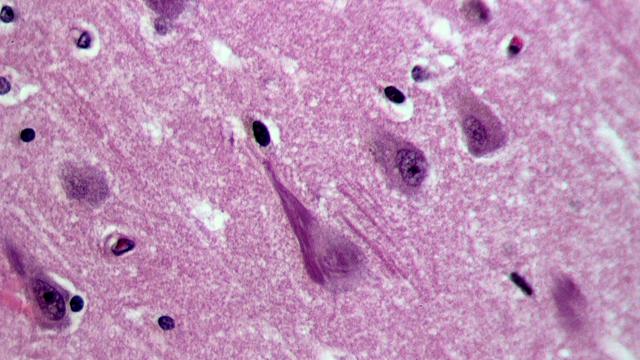

Even before symptoms of dementia become visible, people who develop Alzheimer’s have higher levels of two proteins in their system: amyloid beta and tau. Though we’re still unclear on the exact mechanics, it’s largely assumed that the build-up of both proteins in the brain plays a key role in causing the damage characteristic of Alzheimer’s. Scientists are hopeful they can someday soon use the increasing presence of either protein in our bodies to predict the chances of someone developing Alzheimer’s before they show symptoms. Earlier detection could give potential preventative treatments a better shot of being successful.

On the surface, the researchers didn’t spot any major differences between non-Hispanic whites and black volunteers. Two-thirds of each group were free of any signs of dementia and overall had similar levels of amyloid beta. But there was one clear difference. Levels of tau in patients’ spinal fluid were, on average, lower in black people compared to white.

“With tau, the pattern was the same in African-Americans and whites—the higher your tau level, the more likely you were cognitively impaired—but the absolute amounts were consistently lower in African-Americans,” lead author John C. Morris, neurologist and director of the ADRC at Washington University, said in a statement. “What this may indicate is that the cutoffs between normal and high levels of tau that were developed by studying whites are probably not accurate for African-Americans and could cause us to miss signs of disease in some people.”

When they looked at the genetic make-up of their volunteers, they uncovered something else. The difference in tau was only seen in those who carried a variation of the APOE gene, APOE ε4, which is known to increase the risk of Alzheimer’s. That finding could have far-reaching implications in understanding how and why certain people develop the disease.

“We need to start looking into the possibility that the disease develops in distinct ways in various populations,” Morris explained. “People may be getting the same illness — Alzheimer’s disease — via different biological pathways.”

The authors also said their findings emphasise the importance of studying diverse populations. That certain groups of people are overrepresented in studies is a systemic problem that plagues much of scientific research, and it extends beyond race. Women, for instance, have historically been left out of clinical research, and even to this day, pregnant women are excluded from clinical trials (that might be changing soon, though).

Because the study only looked at a relatively small group of African Americans, Morris said, it’ll take more studies with larger pools of volunteers to figure out whether the link between low tau and APOE ε4 really means anything. And more work is needed to find out if other, similarly important differences among other groups exist as well, he added.

“We’ve been focusing on African-Americans because we have a large African-American community here in St. Louis, but we also need Asian-Americans, Native Americans, Hispanics, everybody to participate in research,” he said. “I think we’ll find we’ve been missing a lot by having such limited study populations in the past. We need to find out what else is going on, so we can develop better therapies that apply to everyone.”