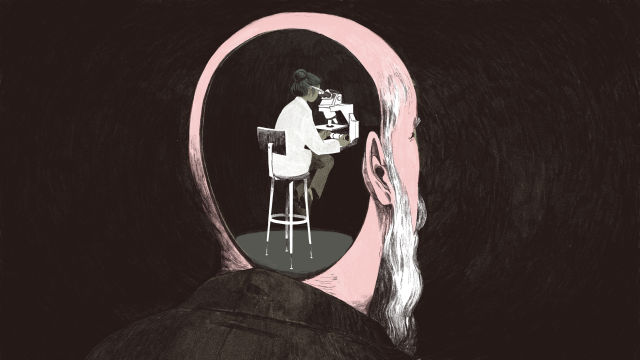

It’s the sort of realisation that ought to make you existentially terrified: All of your thoughts and actions are influenced by countless interconnected factors, most of which you are never conscious of.

Geneticist and immunologist Joshua Milner, a senior researcher at the National Institutes of Health, and other scientists have their own radical theory about how people’s lives can be subtly influenced. Milner thinks that the same thing that protects you from microscopic invaders and makes you sneeze from pollen — your immune system — might just help shape you into a happy, bold extrovert or a shy, anxious outcast, depending on certain genetic variants and your surrounding environment.

All it would take to directly prove this theory is sticking people in a biodome and watching them for decades.

Milner has spent his career trying to unravel how our genes affect the immune system, and how they can sometimes cause it to make us sick. Currently the chief of the NIH’s Laboratory of Allergic Diseases as well as the Genetics and Pathogenesis of Allergy Section, he and his team previously discovered a rare genetic mutation that makes people allergic to cold.

More recently, they seem to have uncovered the genetic cause behind some people’s unexplained symptoms, like irritable bowel syndrome or chronic fatigue.

We asked Milner to describe his ideal experiment to Gizmodo. What he dreams of being able to study isn’t a particular disease or set of symptoms caused by a wayward immune system. Instead, he wants to illuminate something more universal.

“This would help us better define human behaviour, and even human performance in certain cognitive tasks, and why those differences exist,” he told Gizmodo.

In short, Milner would want to create a sealed-off world in which scientists could observe a diverse group of people from birth to death. The researchers would keep track of their social lives and intellectual prowess, ultimately hoping to uncover if the genetic quirks of a person’s immune system can affect their mind, too. Of course, such an experiment would be wildly unethical, and logistically nearly impossible.

Milner and his team have noticed a consistent pattern in their own work. Some of the patients they see with rare genetic diseases often also report behavioural or cognitive problems, like being prone to anxiety or having a particularly poor memory. That might not seem so surprising, given how stressful and frustrating being sick can be, especially if you have a chronic, barely understood disease, as many of Milner’s patients do.

But there’s been research elsewhere suggesting that something deeper is going on between the immune system and our brain.

The cells that make up the immune system use a variety of molecules to help protect us from external harm. One of these molecules is called interferon gamma. Interferon gamma, as Milner explained, is especially useful in creating a specific immune response against severe infections caused by viruses, bacteria, and fungi. Another molecule produced by the immune system, called interleukin 4, helps boost the production of immune cells that fight off parasites like tapeworms.

Our body is frugal, though, and looks to focus resources when it can. So when interleukin 4, or IL-4, is stoked into production, the body cuts back on interferon gamma; conversely, when interferon gamma is called into action, IL-4 is shuffled to the back burner. Putting it very simply, IL-4 and interferon gamma represent two different pathways of the immune system, which are used to fend off the “right” type of threat that’s attacking the body, and act in opposition to one another.

Easy enough so far, but here’s where things get tricky. In animal experiments with mice, researchers led by Jonathan Kipnis at the University of Virginia have found that mice bred without the receptor for interferon gamma or that are incapable of producing interferon gamma become severely antisocial. Those same researchers have also shown that mice unable to produce IL-4 develop serious memory and cognitive problems.

To reiterate here: interferon gamma might make animals more social, while IL-4 might help keep their minds sharp. This could even be another example of the body’s frugality: two genes that have different purposes in both the immune system and the brain.

The fundamental question, Milner said, is whether the same sort of relationship is seen in humans. What if IL-4 is essential for you to be as intelligent as you are right now? And what if interferon gamma is crucial to being sociable? If that’s true, then subtle fluctuations in either could lead to behavioural changes. Maybe the less interferon gamma there is, for instance, the more our brains compensate by subtly nudging us away from other people (who might be carrying all kinds of contagions) — a cognitive immune system of sorts.

“Instead of the immune system preventing the disease, your brain is preventing you from getting into situations where you can catch the disease,” Milner said. “That’s the broad idea — that the brain can step in when the immune system may or may not be able to do it.”

This is the hypothesis advanced by Milner and others—but for now, there’s no direct evidence to support this link between our immune system and our behaviour or cognition. There is, however, some indirect evidence of these complex interactions in people. See, IL-4 is also the major reason why we get allergies. Too much IL-4 makes the immune system overly sensitive and likely to overreact to harmless things like pollen and pet dander.

And a 2017 study showed that people with higher-than-average IQ (an admittedly flawed measurement of intelligence, it should be noted) tend to have more allergies and to develop conditions that are characterised by a lack of healthy sociability, like autism or anxiety disorders. Yet another study in 2018 found that young, educated people with allergies tended to have better spatial reasoning and larger amounts of grey matter in the brain than non-allergic people.

And a study out this week found that boosting people’s level of histamine, another key mediator of allergies, can both negatively and positively affect their long-term memory skills.

Normally, figuring out just how meaningful any of this really is would take lots of incremental research. By necessity, most of it would rely on animal studies that could never definitively prove the effect in humans. In the lab of Milner’s imagination, you’d come much closer to the truth.

In his dream experiment, for example, if the biodome scientists found that people who have more IL-4 in their system were generally more intelligent but less social, that would be evidence for the protein’s effect on the mind. The same would be true if people high in interferon gamma were less intellectually gifted but more sociable. But collecting that kind of data certainly wouldn’t be easy.

“What makes this difficult to study is that we would need genetic information and corresponding validated testing for the cognitive and social outcomes we’d need to measure on very large numbers of people,” Milner explained.

That’s partly because intelligence and sociability are complicated things to measure. A person with better short-term memory or better spatial reasoning might be better at solving puzzles, for instance, but that doesn’t necessarily make them smarter in every way. Likewise, being outgoing isn’t the only way we’d consider someone to have good social skills.

As for how large a group you’d need to study, the number would depend on the kinds of people you could recruit, genetically speaking.

“You would need hundreds and hundreds of people to get a sense of this. Or you’d need hundreds of people with a rare mutation who aren’t terribly sick. That’s not very easy to find,” Milner said.

It’d be great to study at least some people with genetics that make them especially responsive to either interferon gamma or IL-4. But genes aren’t the whole picture. It’s also how a person’s genes interact with their environment. In the animal experiments, the behavioural effects of interferon gamma or IL-4 were seen in otherwise healthy mice, meaning they weren’t dealing with an infection or allergic reaction.

But in the real world, infections and allergic triggers happen all the time, and they spark a greater production of interferon gamma or IL-4, respectively. So these events and their frequency could affect cognition and sociability, too.

What really makes this experiment nearly impossible are the logistics involved. There are a lot of variables to keep track of all at once, and you’d need a dedicated team of scientists to closely observe a large group of volunteers as early in life as possible. More impractically, you’d want the scientists to not only watch one group of people for a lifetime, but observe multiple generations.

When I suggested to Milner that his ideal set-up sounded like the serious version of the Pauly Shore-helmed 1996 classic Bio-Dome (and the real-life, closed environment systems that inspired the movie, I suppose), he graciously accepted the comparison.

“The biodome would be helpful,” Milner said, adding that it would let researchers carefully study the interactions between environment and genes.

“Maybe you would want to get allergic people in there, so you could see what happens when the allergic stuff is coursing through their veins, but you’d also want to have people who don’t have allergic disease,” he provided as an example. For people less responsive to interferon gamma, he added, a biodome could also carefully control the kinds of bacteria they’re exposed to, including those that can cause infections or not.

Realistically, Milner said, the closest scientists will come to studying this link in humans is to look at people with exceptionally rare mutations that make them either very receptive to interferon gamma and IL-4, or deficient in one type of receptor or the other. Milner and others have already started to design what these studies could look like. But because these people are so rare by definition and oftentimes sick in many ways, it’ll be hard to extrapolate what they find to the typical person. Still, Milner is convinced there is something concrete to the theory.

“Is it possible that none of these genetic differences contribute to our behaviour? I’d find that shocking,” he said. “They must affect something.”

Milner repeatedly points out that these foibles of the immune system and how they affect the mind shouldn’t be seen as universally bad or good, if they do exist. A better working memory, aided by a greater response to IL-4, might make you better at taking exams, but perhaps you’d be more anxious or antisocial.

On the flip side, if you have a particularly strong response to interferon gamma, you might get less sick from the common cold and be more outgoing, but at the cost of being the worst member of your weekly trivia night (these examples are gross simplifications, of course).

More than anything else, the interferon gamma/IL-4 theory showcases just how tangled the unseen forces that govern our lives really are. Milner said:

The way the real world works won’t be that simple. But it could help explain some of the inclinations of our behaviour. When we respond to threats of infection, do our genetic determinants cause different responses to it? Do we get more or less anxious depending on what’s going on? Is that dictated genetically, as opposed to because we’re in a blue or red state, or whatever else it is?

That we perceive the threat differently based on our ability to fight an infection? Think all of the things that might shake out from that.

Several studies, for instance, have found that conservative-leaning people are more likely to express disgust and fear contamination than their liberal counterparts.

Those same people, Milner noted, are more likely to worry about different-looking immigrants. Without excusing that behaviour in the slightest, maybe it’s worth exploring if our genes and immune system can help explain some of the worst impulses of humanity, too.