A new case study from Pittsburgh highlights the resilience of the human brain. It details a boy who, despite losing one-third of the right hemisphere of his brain when he was six, is now a mostly ordinary 10-year-old. Though he can’t see past the left side of his face, his brain has compensated for the loss in some ways by forming new neural connections, allowing him to recognise faces and objects as easily as anyone else.

The boy, referred to as U.D. in the paper published Tuesday in Cell Reports, started having severe seizures at the age of four. The seizures were caused by a slow-growing brain tumour found in the occipital and temporal lobe of his right hemisphere.

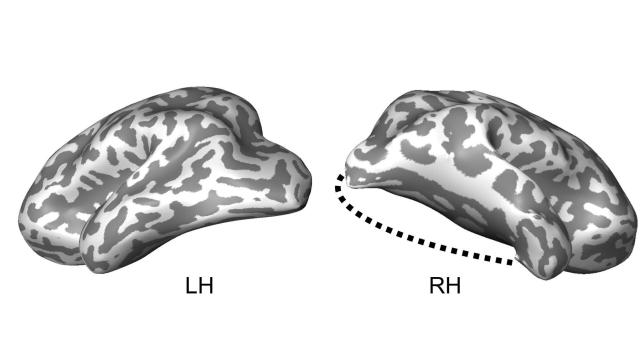

Eventually, after drugs and other treatments did little to alleviate his symptoms, the boy’s family opted for a radical option: Just before turning seven, the boy had his entire occipital and much of the temporal lobe removed, accounting for one-third of the right hemisphere.

The drastic surgery was a success. The boy’s seizures went away, as did the tumour. But there was no telling how he would progress after losing these crucial parts of the brain.

The occipital lobe acts as a command centre for the visual information we take in from our eyes, letting us perceive vision and helping us decide what those shapes and colours mean to us. The temporal lobe, among other things, also takes in and processes visual and auditory information from the outside world.

Because the boy had received his care at the Children’s Hospital in Pittsburgh, he and his family agreed to participate in a project run by Marlene Behrmann, a cognitive neuroscientist at Carnegie Mellon University.

Behrmann and her team have long been interested in understanding how the brain allows us to see the world, and how that process can be affected. Their project has been meticulously studying patients such as U.D. — via regular brain scans and visual tests — to find out what exactly happens to the brain after parts of it involved in vision are damaged or removed.

The brain is already known to sometimes reorganise itself when damaged, forming new connections between neurons in other areas to compensate for the ones that were lost. But research into the brain’s plasicity, as it’s called, has mostly been limited to how it affects our memory or learning ability, according to Behrmann.

“There is no other longitudinal study like this that has given these kinds of unprecedented insights into how the brain works,” Berhmann told Gizmodo.

U.D.’s brain wasn’t able to replace the low-level functions of the right hemisphere’s visual processing, meaning he can’t visually perceive the left-hand side of the world. But his brain’s left hemisphere did take over higher order functions typically found in the right hemisphere.

“His visual behaviour is excellent, absolutely normal,” Behrmann said. “Even though he only has one visual system, it’s been reconfigured to do the work of both hemispheres.”

Much like everyone else does with their blind spots, U.D. compensates for his left-side blindness by moving his eyes or head around, with little awareness of what he’s missing. And the impairment hasn’t impacted his growth and development: He has no signs of cognitive or other health problems.

“He is awesome. He’s as smart as anyone. He’s thoughtful, curious. His family has been incredibly cooperative with our project,” Behrmann said.

There are still a lot of questions about the limits of brain plasticity in vision, questions that Behrmann hopes her project’s eventual findings can help answer. The brains of children older than U.D. might not be able to reorganise as effectively as his did, while younger children might do even do better, letting them see more of the world.

Other factors, such as a child’s cognitive function before surgery or the exact cause of their seizures, might also play a role in the prognosis.

The type of surgery U.D. underwent to treat his epilepsy, while radical, is often successful, eliminating seizures 60 to 70 per cent of the time. But it’s rarely carried out, even as a last resort. Behrmann says her team’s research could possibly alleviate some of that reluctance, by allowing doctors and families to better predict how their children will respond.

“Families often tell us that they were very hesitant to have this procedure performed, which is completely understandable. I mean, if someone comes and says they’re going to cut out my kid’s brain, that’d be terrifying,” she said. “But many of the kids do really well. And many of the parents say they wish they had allowed their kids to go through surgery earlier.”

Behrmann and her team plan to continue following the progress of those like U.D., though she personally has no worries about his future.

“I have great hope that this kid is going to do wonderful things in the world,” she said. “And the goal is for all of these kids to be able to do that.”