As far as humans are concerned, Mars has two stories. One is in the present: We’re trying to send our ships and our astronauts to the Red Planet in order to understand what it’s like today. But much of that work is meant to tell a second story – what the planet used to be like.

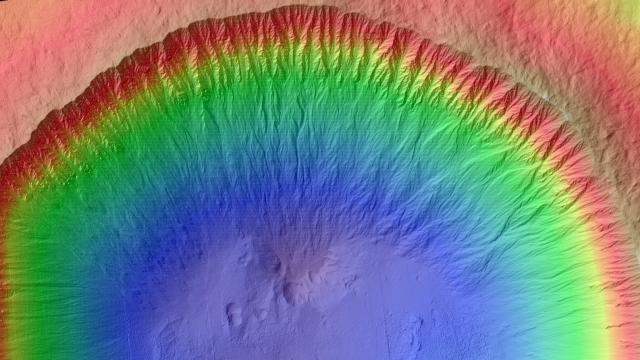

An image of a gullied crater on Mars, taken by the HiRISE camera. Image: HiRISE

A pair of new results continues to elucidate that history. One discusses the planet’s earliest days, finding that its crust could have solidified even earlier than Earth’s. The second adds evidence to the idea that surface water, perhaps from rain or melting ice, could have produced the planet’s network of branching valleys.

All of this is to say that while Mars might look like a dead, red orb today, such was not the case in the past.

“The main thing we know that makes life possible is the presence of liquid water,” Linda Elkins-Tanton, an Arizona State University planetary scientist who was not involved with either new study, told Gizmodo.

“And we know that it could have existed all the way back to just after that crystallisation and solidification” of the planet’s crust.

Scientists have thought that Mars finished forming as a planet around five million years after the birth of the Solar System, then took somewhere between 30 million and 100 million years for its crust to solidify.

But how could we understand such a process from Earth? Well, at some point in Mars’ history, pieces of the planet’s crust broke off and made it all the way to Earth in the form of meteorites. Inside these meteorites are clues to the planet’s early history, such as when its crystals formed.

The first team of researchers analysed Martian meteorites for zircons, special crystals that form out of melting magma and can selectively trap uranium atoms – but not lead atoms. That’s important, because uranium decays into lead through radioactivity. That means any lead the researchers find in the zircon must be from trapped decaying uranium, allowing for a fairly precise way to determine the zircon’s age.

Analysing seven zircons, they found ages from 4.476 billion to 4.430 billion years old, according to the paper in Nature.

The researchers used this data to infer that the Martian crust could have solidified only 20 million years after the planet formed, though their analysis also reveals that perhaps in its first hundred million years, the crust melted and solidified.

Still, they’re old. “These zircons, which are about 100 million years older that the oldest terrestrial zircons, tell us that Mars had evolved into a fully differentiated planet with a crust much earlier than Earth,” cosmochemistry professor Martin Bizzarro from the University of Copenhagen told Gizmodo.

Elkins-Tanton was impressed with the team’s analysis, and told Gizmodo that it would be exciting (but very difficult) to learn exactly where on Mars the meteor came from, then go there and continue the analysis.

Fast forward to present-day Mars, and you’ll notice channels cut into the planet like a network of rivers. Many think that, well, these were a network of rivers.

Another team analysed the angles that river channels on Earth make when they branch off from a parent water source. They also performed the same analysis with the Martian channels.

The patterns on Mars looked closest to river networks in dryer areas on Earth, which have smaller branching angles than wetter areas, according to the paper published in Science Advances.

That means “you need meltwater, or you need precipitation”, rather than groundwater, to create what the researchers saw, said professor Hansjörg Seybold from ETH Zürich. “We would then hypothesise that Mars’ past climate had an active hydrologic cycle.”

You might not be convinced by an analysis that just compares the shapes of channel systems. That was a limitation that professor Kirsten Siebach from Rice University, not involved with either study, mentioned to Gizmodo – it’s hard to tell what other factors might lead to certain shapes.

But she thought the analysis was still interesting and that the idea that Mars had meltwater or precipitation carving these channels is convincing, if you add the bulk of recent evidence.

“I think it’s supporting a story as part of series of papers consistently telling us that we have to think about Mars a little more like Earth,” she said, “which is exciting.”

There’s much more to learn, and as usual, it’s hard to tell exactly what our cosmic neighbour once looked like. But combined with other recent news about organic molecules on the Red Planet, our view of Martian history is becoming more clear. Perhaps it truly was a little more Earthlike than its current appearance suggests.