“If I gave two fucks – two fucks about streaming numbers, would have put Lemonade up on Spotify,” Beyoncé proclaims on “NICE” from her joint album with Jay-Z which they dropped exclusively on Tidal over the weekend. Unfortunately for those emotionally or monetarily invested in the streaming service, your sudden need to download Tidal quickly dissipated when by Monday morning, Everything Is Love could be found on Apple Music and Spotify’s paid tier.

Photo: Getty

When Tidal’s most public-facing owners can’t survive more than 48 hours in a Tidal-only world, what could’ve gone so wrong with the company? Even the heirs to Prince’s estate are looking to terminate a recently announced deal between Tidal and the deceased singer, TMZ reported on Tuesday.

Tidal wanted to save the music industry, and instead, it’s losing exclusives and right now stands accused of fudging subscriber numbers, manipulating streaming numbers, providing late payment to labels, and in some cases not paying artists at all. (Some of which, Tidal vehemently denies.) Problems began from the start with the company.

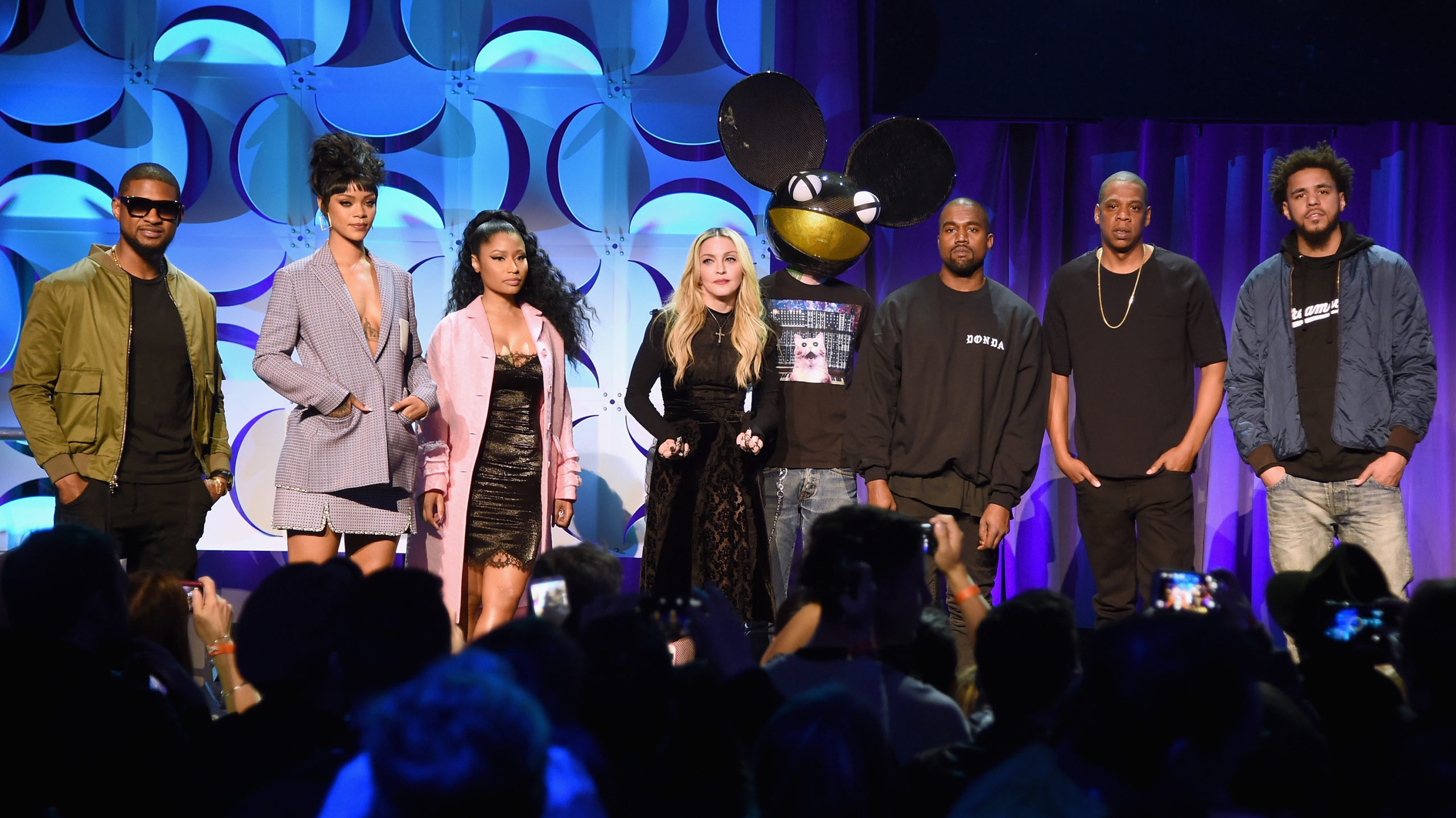

Three years ago, Jay-Z, one of the world’s most successful rappers, publicly debuted Tidal alongside a who’s who of music’s power players, including Arcade Fire, Beyoncé, Daft Punk, Madonna, Rihanna and Kanye West – who despite public bluster is still invested.

Jay-Z pitched his music streaming company against the likes of Apple, Spotify and YouTube – tech companies the music industry routinely found ways to blame for their own industry’s short failings. The constant complaints levelled against these billion-dollar corporations was that artists weren’t being fairly compensated for their work. The dollars that used to be made from CDs and even digital downloads shrunk down to fractions of cents per individual song streams.

Alicia Keys, one of the signers, in her rallying cry for the freshly rebranded company described Tidal as “the first ever artist-owned global music and entertainment platform”. Without a free option and in fact by offering a premium, higher audio quality mode, Tidal proposed that you should pay it to stream music and feel good about it, too.

“Will artists make more money? Even if it means less profit for our bottom line, absolutely,” Jay-Z boldly asserted to Billboard back in 2015. “Less profit for our bottom line, more money for the artist; fantastic. Let’s do that today.”

No longer were major labels going to hold all the power in the music industry, nor would aloof tech companies; no, this new era belongs to artists. The issue that appeared in this utopian vision is that music’s ruling class weren’t always looking out for those underneath them.

Dagens Naeringsliv, a Norwegian newspaper that sits diligently on the Tidal beat, reported in May that the company allegedly falsified streaming numbers for Kanye West’s The Life of Pablo and Beyoncé’s Lemonade.

The newspaper partnered with the Norwegian University of Science and Technology’s Center for Cyber and Information Security, which concluded that over 90 per cent of Tidal users saw manipulated listening stats and that the company logged over 300 million fraudulent streams for the two artists.

Tidal vehemently denied the claims, but in the 78-page report, the centre concluded that it’d be highly unlikely for this level of data manipulation to occur from outside of the company. While it was a scandalous report, such claims are not outside of the ordinary for Tidal since Jay-Z’s purchase.

Tidal’s lofty artist-first aspirations

Months prior to Jay-Z’s entry into the music streaming market, another music superstar shook music streaming’s still-feeble foundation. Taylor Swift published a 2014 op-ed in The Wall Street Journal where she championed the traditional album format and engaging with one’s fans while dismissing music streaming.

“Piracy, file sharing and streaming have shrunk the numbers of paid album sales drastically, and every artist has handled this blow differently,” she wrote.

Far from an outlier opinion, artists from Swift to Radiohead’s front man Thom Yorke have spoken profusely about their displeasure with Spotify. Swift took it the next level by pulling her catalogue from the service, suggesting that artists with enough clout could enter this new age on their own terms.

Jay-Z pitched Tidal to musicians as well as fans as an opportunity to embrace this new future without feeling as though they were turning backs on their favourite artists. In April 2015, Jay-Z tweeted that Tidal would offer 75 per cent royalties for artists, producers and songwriters.

However, Eric Harvey, an assistant professor at Grand Valley State University and frequent music commentator told NPR, “These are the one per cent of pop music artists in the world right now… While technically they are performing the same sorts of labour as independent musicians are, they’re doing so at a fairly radically different scale.”

Harvey observed that despite the big talk, this service potentially might only serve those powerful enough to stand next to Jay-Z on stage.

Usher, Rihanna, Nicki Minaj, Madonna, Deadmau5, Kanye West, Jay-Z and J. Cole onstage at the Tidal launch event #TIDALforALL at Skylight at Moynihan Station on 30 March 2015 in New York City. Photo: Getty

Tidal was born from Jay-Z’s March 2015 purchase of Aspiro, the Norway-based company behind the European music streaming service WiMP and Tidal. The mogul wanted to break into the emerging streaming music space and conveniently beat to market Apple’s soon-to-launch Apple Music.

Shortly after the company’s purchase, Asprio’s CEO Andy Chen left, kicking off a number of high profile executive exits from the company. Despite the c-suite turnover, Jay-Z announced via tweet in September that one million people were using the service, without clarifying if this was paying subscribers, trial accounts mixed with subscribers, or what. The numbers put Tidal significantly behind Apple Music, Pandora and Spotify, but there appeared to still be growth for the young streaming service.

Tidal hit 2016 running by partnering with one of its investors, Rihanna, on the release of Anti, the pop star’s most recent album, by offering one million free downloads that arrived with a Tidal trial. The company repeated a similar exclusive strategy with Kanye West’s The Life of Pablo and Beyoncé’s Lemonade – again another pair of artists who invested in the company.

The New York Times reported that Lemonade alone added 1.2 million subscribers to Tidal, potentially putting the company at 4.2 million subscribers; in April 2016, Apple Music’s global reported user base was 13 million and Spotify’s was near 100 million, according to an industry source. Jay-Z and his crew of pop gods created at least on paper a small, but growing, music streaming service.

Jay-Z’s bad maths

Nestled between high-profile releases by West and Beyoncé, Tidal announced it sent a legal letter to the former owners of Aspiro for providing misleading information about the company’s subscriber base before Jay-Z’s purchase. Tidal said in a statement:

It became clear after taking control of Tidal and conducting our own audit that the total number of subscribers was actually well below the 540,000 reported to us by the prior owners. As a result, we have now served legal notice to parties involved in the sale. While we cannot share further comment during active legal proceedings, we’re proud of our success and remain focused on delivering the best experience for artists and fans.

“Baseless” is how Anders Ricker, the director of communications at the Schibsted Media Group, which was the previous majority owner of Aspiro, described the accusations made by Tidal.

In 2017, the Swedish site Breakit spoke to Taina Malén, who was formerly on the board of Aspiro, about the case Jay-Z put towards her former company. She dismissed it as “nothing”, saying Tidal never followed-up with any actions after its initial accusation of wrongdoing towards Aspiro’s former owners.

Tidal’s subscriber numbers received such intensified attention because initial adoption of the service appeared to be slow and the company ceased providing any user base information, while its competition continued to show growth.

An extensive 2017 Dagens Naeringsliv report alleged that Tidal’s subscriber numbers were inflated. The paper said according to multiple sources and documents that Tidal’s true subscriber base in September 2015 was closer 350,000 – Jay-Z tweeted it was 1,000,000 – and in March 2016 was 850,000 – although Tidal said 3,000,000.

According to documents obtained by Dagens Naeringsliv, in late 2015 after Jay-Z’s purchase, Tidal saw a significant increase in its Denmark and Norway subscriber numbers, growing in the two countries by 170,000 subscribers. However, Dagens Naeringsliv reported that these numbers were artificially inflated according to Arthur Sund, the former head of business intelligence at Tidal, whose team noticed the sleight of hand the following day.

Sund said he was frustrated the company was paying out money to labels for subscribers who weren’t even using the service just to show improving subscriber growth. “I deemed it unethical and asked critical questions,” said Arthur Sund when speaking to Dagens Naeringsliv. “But I considered it mostly idiotic to pay the record labels for customers we did not really have.”

That reported action by the company raised a number of red flags about Tidal’s greater business practices. Royalties for all major music streaming companies are calculated using a pro rata model, so the money from subscriptions or potentially ad revenue is put in a massive pot and divided by the per cent of streams that an artist accumulates.

Simply put, the more streams an artist accumulates the more money they will make to the detriment of artists who aren’t able to achieve the same number of streaming numbers.

That issue came to light when Dagens Naeringsliv reported that Tidal had added millions of extra streams to albums by Beyoncé and Kanye West. The paper said it obtained a hard drive containing inflated streaming numbers and compared it with the number of streams on the royalty sheets of Universal Music Group. The two numbers reportedly matched, and Tidal reportedly paid out $US2.38 million ($3.2 million) to Universal in February 2016, the same month as the release of The Life of Pablo.

DN‘s report ultimately accuses Tidal of paying the major label for illegitimate streams, while attempting to boost its numbers. If these allegations are true, then artists paid by Tidal that month would have seen their paychecks shrink as Kanye West’s share of the total percentage grew.

Nine figure chaos

Shuffling through CEOs – Tidal is currently on its fourth CEO since Jay’s purchase – and allegations of falsified subscriber and streaming numbers, unfortunately aren’t the only issues facing Jay-Z and Tidal.

In early 2016, the New York-based band the American Dollar filed a class-action lawsuit against Tidal for unpaid royalties, but Tidal responded by saying the company did pay the royalties to the band.

Back in September 2016, Dagens Naeringsliv also reported that Tidal had racked up 107 default notices for lack of payment, including to the Oslo World Music Festival, numerous record labels and advertising firms.

The ups-and-downs of 2016 were placed in stark relief at the top of 2017, when Jay-Z secured a $US200 million ($271 million) investment from Sprint through purchasing a third of the music streaming company – an amount that dwarfed the initial $US56 million ($76 million) that Jay-Z invested when he bought Aspiro.

The move was a bit surprising. Recode in reporting on the story mockingly used the headline: “Jay Z is selling a third of Tidal, which makes sense. Sprint is buying a third of Tidal, which makes less sense.”

The company’s concerning financial standing revealed itself in reports over the years that said in 2014 the company lost $US10.4 million ($14 million); $US28 million ($38 million) in 2015; then nearly $US44 million ($60 million) in 2016. Those reports aligned with the dim realities of music streaming, where even Spotify with over 170 million users and over 70 million paying subscribers still hasn’t turned a profit in nearly 10 years. Jay-Z’s company took a big swing in a market where even its most successful competitors are constantly bleeding money.

Jay-Z’s monetary concerns didn’t end with Tidal. In early May, TMZ reported that the Norwegian law firm Roschier Advokatbyrå AB filed a lawsuit against the rapper for unpaid legal bills that occurred when buying Aspiro, which the law firm confirmed to Gizmodo but didn’t care to offer any more comment on the case.

The Swedish bank SEB also claimed that Jay-Z owed it hundreds of thousands of dollars in unpaid invoices in association with the purchase of Tidal, which it reaffirmed to Gizmodo when asked for comment.

Shoddy stats, legal mess

Lawsuits and investigations were only starting to pile up for Tidal last month. After the initial May Dagens Naeringsliv report about falsified streaming numbers, a number of European music groups announced probes into the company. The organisations expressed concerns about Tidal potentially depriving money for artists they represented and increasing reports that Tidal was chronically falling late in payments to labels.

After these reports, Tidal said: “we have engaged an independent, third party cyber-security firm to conduct a review of what happened and help us further protect the security and integrity of our data,” but still the organisations pushed back against the company.

TONO, a Norwegian musical collection group that represents producers and songwriters, filed a report to Norway’s National Authority for Investigation and Prosecution of Economic and Environmental Crime.

Willy Martinsen, TONO’s director of communication, said to Gizmodo over email that the organisation remained in conversation with Tidal and other musical societies, and repeated: “As we have stated continually we believe the complaint should also be in Tidal’s interest because they claim the data has been stolen and manipulated.”

In Denmark, Koda, another music performance right organisation, reiterated to Gizmodo that it’s hoping to review the same data Dagens Naeringsliv used to report their story. The group says it is also allowing time for Tidal and the Norwegian police to conclude their investigation before continuing with other measures such as a potential external audit.

The MFO, a Norwegian musician union with over 8600 members, reported Tidal for fraud to the Norwegian police. GramArt, another musician’s organisation, reported Tidal to the Norwegian authorities.

The group also responded to a statement from Tidal that implied such potential manipulation wouldn’t affect the payout for other artists. “Neither Tidal nor the specific artists would have gained economic benefits if the allegations were true,” said Tidal. A spokesperson for GramArt disagreed, arguing that such streaming data alteration would trickle down and effect others on the service because of the pro rata model used by Tidal.

American performance rights organisations such as ASCAP and BMI so far have remained silent about pursuing any investigations into Tidal payments issues – Gizmodo reached out to both companies for comment.

Tidal’s initial public response to all of these accusations started off sharp. When Dagens Naeringsliv first reported on the alleged falsified Beyoncé and Kanye West streams, the company fired back in an email to Gizmodo, saying:

This is a smear campaign from a publication that once referred to our employee as an “Israeli Intelligence officer” and our owner as a “crack dealer.” We expect nothing less from them than this ridiculous story, lies and falsehoods. The information was stolen and manipulated and we will fight these claims vigorously.

The company’s pointed public statement referenced a 2017 Dagens Naeringsliv article that highlighted Tidal’s reported manipulation of subscriber numbers. The “crack dealer” comment was in reference to Jay-Z, who while an accomplished businessman, sold millions of albums and won Grammy awards while rapping about dealing drugs. The other person mentioned in there response (“Israeli Intelligence Officer”) is Lior Tibon, who according to his LinkedIn page is Tidal’s Chief Operating Officer and served in the Israeli Defence Force from March 2002 to February 2006.

Tidal’s public response to these accusations isn’t to highlight the great work they have done or the artists who are thriving on the platform, but rather to tear down those who speak any word of criticism.

When reached for additional comment on a number of recent accusations facing the company, Tidal denied at length the reporting done by Dagens Naeringsliv. Reached by Gizmodo for comment, Tidal reiterated an argument it’s provided to other publications:

We reject and deny the claims that have been made by Dagens Næringsliv. Although we do not typically comment on stories we believe to be false, we feel it is important to make sure that our artists, employees, and subscribers know that we are not taking the security and integrity of our data lightly, and we will not back down from our commitment to them.

Jay-Z wanted Tidal to bring in a new guard for the streaming era – a company that potentially prioritised compensating the artists, unlike tech-first gatekeepers such as Spotify and YouTube. But between shoddy stats and legal troubles, Tidal no longer appears to be offering a better solution to the problems artists are still facing. The company may continue as a vanity project for music’s privileged elite, but its goals of breaking down music industry walls feels over.