Pluto may not be a planet, but it remains one of the most intriguing objects in the outer Solar System. Its unexpected chemical composition has confounded scientists for years, but a new theory may finally hold the answer. Pluto, according to a pair of Southwest Research Institute scientists, is basically an overgrown comet.

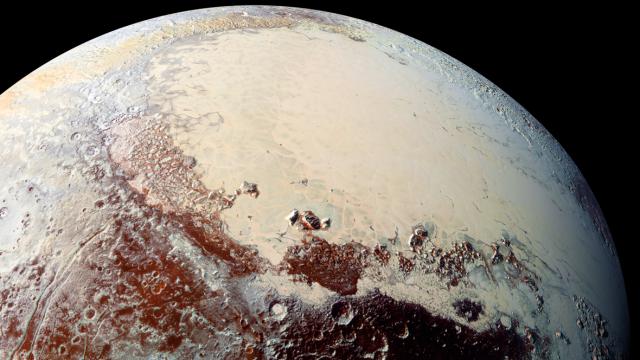

One of Pluto’s most striking features is its bright Tombaugh Regio, a smooth, heart-shaped area consisting of two giant lobes. The western half, called Sputnik Planitia, is a large glacial plain packed with frozen nitrogen and other ices. The surprising amount of nitrogen on Pluto contributes to its dynamic surface features and ongoing geological and atmospheric processes, but as new research published this week in Icarus shows, it may also tell us something about where this dwarf planet came from.

Astronomers typically assume that Pluto formed like the other planets, even though Pluto is not a planet. Around 4.6 billion years ago, the theory goes, a distant rocky core formed within the Sun’s protoplanetary disc, and its gravity gathered various gases and ices. And voilà, Pluto came to be.

A new theory, dubbed the “cosmochemical model of Pluto formation,” is now challenging this long-held view. Pluto, according to Southwest Research Institute scientists Christopher Glein and J. Hunter Waite Jr., is basically a giant comet. The research presented in the new study is very preliminary, and more work will be needed to flesh this idea out, but it’s an intriguing possibility.

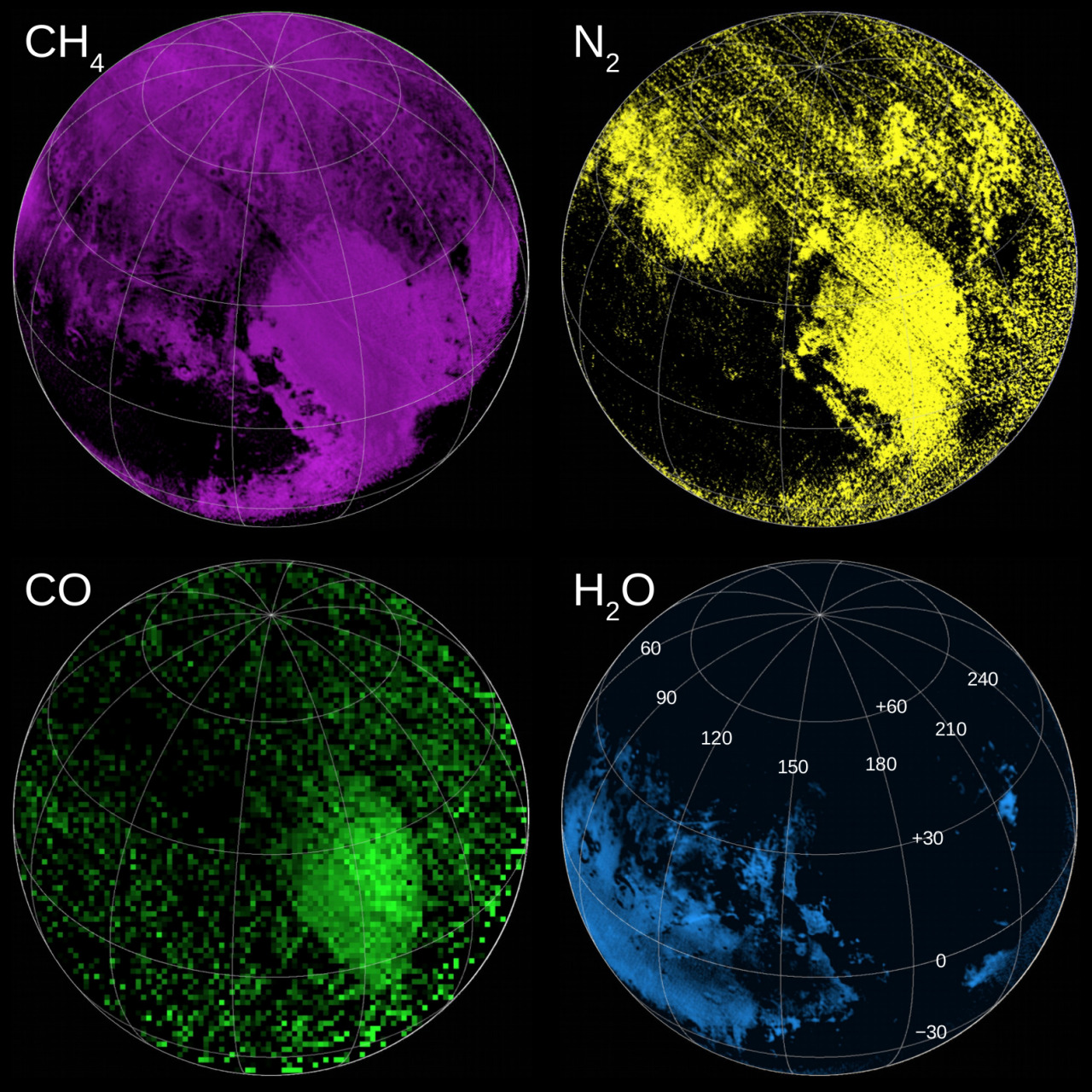

Maps indicating regions rich in methane (CH4), nitrogen (N2), carbon monoxide (CO), and water (H2O) ices. Sputnik Planitia shows an especially strong signature of nitrogen near the equator. Image: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute

The researchers came to this conclusion by studying data collected during NASA’s New Horizons Pluto mission and ESA’s Rosetta mission to the comet 67P/Churyumov – Gerasimenko.

“We found an intriguing consistency between the estimated amount of nitrogen inside the [Sputnik Planitia] glacier and the amount that would be expected if Pluto was formed by the agglomeration of roughly a billion comets or other Kuiper Belt objects similar in chemical composition to 67P, the comet explored by Rosetta,” explained Glein in a statement. Unlike asteroids, comets contain lots of ice and gas – the potential building blocks of planets.

For the study, the researchers estimated how much nitrogen and other chemicals exist on Pluto at this present moment, and how much may have leaked into space over time. Their investigation suggests the nitrogen on Pluto is of a “primordial species,” meaning it gradually accumulated over time via cometary accretion.

“It was previously very difficult to study the chemical history of Pluto because of the paucity of relevant data,” the researchers write in their study. “The New Horizons and Rosetta missions have changed the game by providing valuable new data, clearing paths to resolving this issue that is central to understanding the nature of Pluto.”

Importantly, the researchers also had to explain the apparent lack of carbon monoxide on Pluto as it exists in proportion to nitrogen (i.e., why the ratio of N2 to CO appears out of whack). The dearth of primordial carbon monoxide, the researchers hypothesize, is because it’s buried deep in Pluto’s surface ices, or it was destroyed when liquid water existed on the surface.

“Our research suggests that Pluto’s initial chemical makeup, inherited from cometary building blocks, was chemically modified by liquid water, perhaps even in a subsurface ocean,” explained Glein.

The newly presented cosmochemical model of Pluto formation explains these observations rather nicely, but as the researchers admit, a solar model of Pluto formation also works. According to this alternate theory, Pluto formed from very cold ices with chemical compositions that more closely matches that of the Sun. So with two equally plausible theories, there’s clearly more work to do.

What’s more, prior research suggested the slow leakage of Pluto’s atmospheric nitrogen is due to a cooling effect high in Pluto’s atmosphere. The dwarf planet’s cold, dense atmosphere may explain why Pluto has retained features like Sputnik Planum and its frozen nitrogen.

“This paper is an exciting example of the science that can be achieved when combining data from different, international, planetary science missions,” James Tuttle Keane, a planetary scientist at Caltech who wasn’t involved with the new study, told Gizmodo. “Understanding how these worlds formed can provide important clues into how the rest of the Solar System formed. There’s been long debate about the role and significance of comets in the construction of planets. For example, scientists have long wondered whether comets were the source of the Earth’s water or whether they were important for the delivery of the ingredients for life. This study represents a new piece to this long standing puzzle.”

While these results are interesting, Keane says there are still a lot of outstanding questions.

“We still don’t know a lot about the chemistry of Pluto. New Horizons provided an unprecedented and revolutionary view of Pluto, but it only scratched the surface,” he said. “While we can learn more from ground-based telescopic observations, laboratory experiments, and theoretical modelling — there may be no substitute for returning to Pluto. A future Pluto orbiter with mass spectrometers could ‘taste’ the chemistry of Pluto, much like how the Cassini mission investigated the chemistry of Saturn’s moon Titan.”

In addition, Keane says this work begs for continued exploration of other comets.

“While Rosetta yielded incredible details about 67P, we still don’t know if 67P is truly representative of the Solar System’s vast inventory of comets,” he said.

The authors of the new study haven’t proven that Pluto formed from a billion comets, but they have started an intriguing conversation — one that’s challenging our conceptions of how large and distant celestial bodies came into existence.

[Icarus]