The self-proclaimed “space kingdom” of Asgardia is currently limited to a glitchy website and a satellite orbiting the Earth about the size of a loaf of bread. But Asgardia wants to be much more than just another micronation: It aims to join the United Nations and eventually send its citizens to lower Earth orbit where they will live on habitable platforms and defend the planet from “space threats” such as asteroids and solar flares. All of this is supposed to happen after Asgardia establishes a parliament from the more than 180,000 people who have registered online as Asgardian citizens, a lax process that in practice requires little more than filling out basic personal details and accepting Asgardia’s constitution.

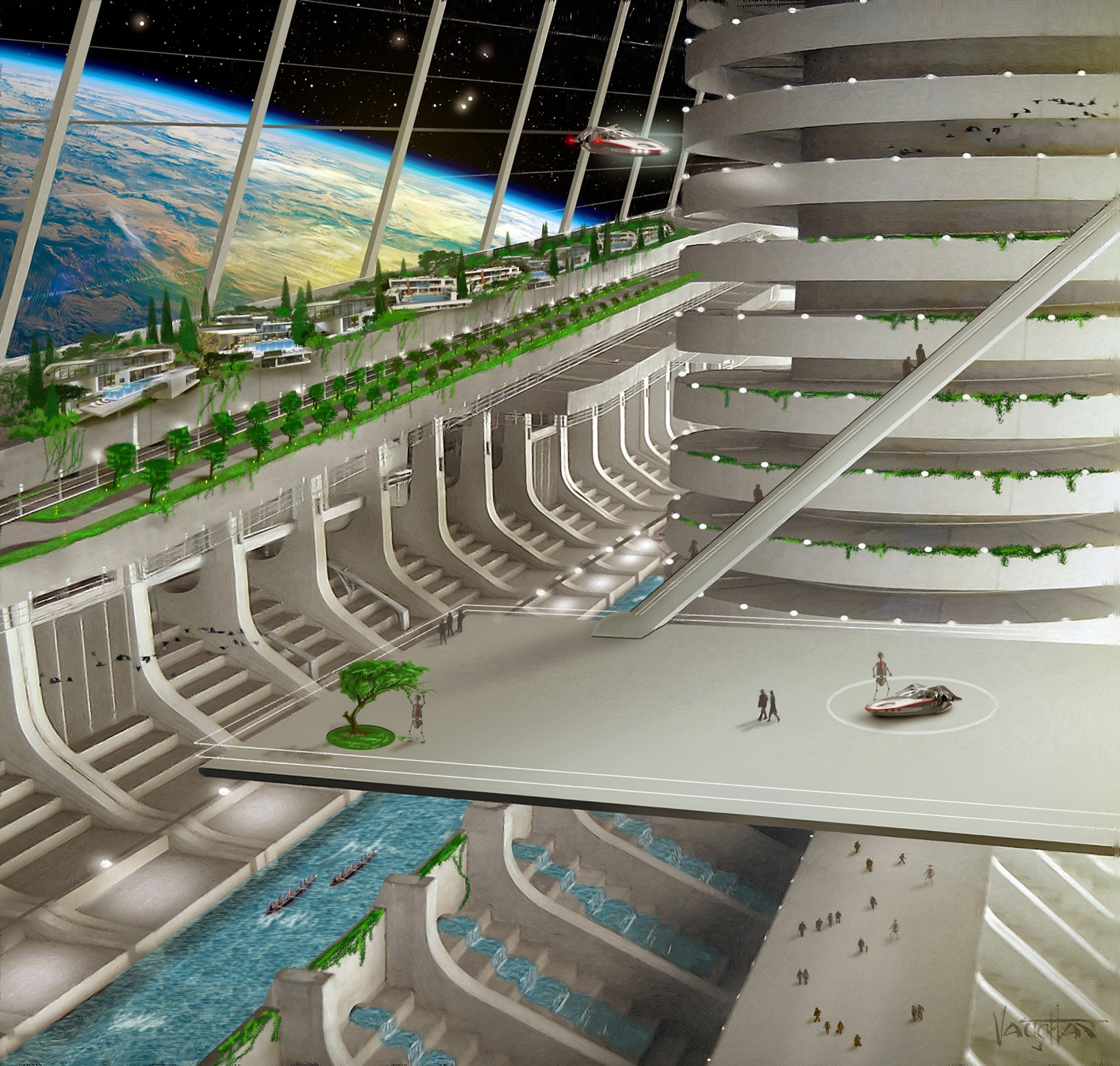

Concept art for the Space Kingdom of Asgardia’s Earth-orbiting station. Illustration: James Vaughan (Asgardia)

However, it turns out that it isn’t so easy to fashion a parliament out of an often-quarrelsome group of idealists from almost every single country on Earth, especially when Asgardia’s eccentric founder stands accused by some of his fellow Asgardians of harbouring an authoritarian streak. Asgardia’s first elections have been plagued by issues ranging from a buggy website to poor vetting procedures, and the messy process even culminated in a conspiracy theory that some obscure candidates were handpicked by Asgardia’s ruler to win so they could secretly do his bidding when parliament officially begins. At the height of the chaos, Nissem Abdeljelil, a 31-year-old Asgardian, told me she was worried all the problems didn’t bode well for Asgardia’s utopian dreams. “We brought with us all the old reflexes of Earth’s politics,” she said. “It’s disappointing.”

As described on its “concept” page, Asgardia’s utopian mission is threefold: Legal, philosophical and scientific. Legally, Asgardia hopes to establish history’s first sovereign nation in space. Philosophically, Asgardia aspires to escape humanity’s endless divisions by opening up space citizenship to pretty much anyone on Earth and uniting them behind the cause of defending the planet. And finally, Asgardia wants to be a hub of non-military scientific progress, sharing its knowledge with anyone who wants it. Combined with an almost retro sci-fi appeal, this unabashedly idealistic vision has attracted scores of devotees from Bangladesh to Argentina and everywhere in between.

Concept art for the Space Kingdom of Asgardia. Illustration: James Vaughan (Asgardia)

Unsurprisingly, Asgardia hasn’t come close to achieving these goals quite yet – never mind the massive technical challenge of building habitable platforms in lower Earth orbit or even the vague plans for “settlements on the Moon and possibly on other celestial bodies”. But the space kingdom does have a tiny presence in space in the form of Asgardia 1, a nanosatellite launched last November that contains half a terabyte of data, including Asgardia’s flag, coat of arms, and constitution, along with personal data uploaded by some 18,000 eager Asgardians. The satellite may not seem like much, but Asgardia hopes to use it to bolster its claims of being a nation since it constitutes some form of physical “territory”, while it also represents the first step in an ambitious goal of sending a “constellation” of satellites into orbit before the platforms are built. Asgardia’s operations are currently being managed by a Vienna-based organisation called NGO Asgardia, which has a team of about 50 paid administrators and is funded by Asgardia’s founding father, Russian aerospace tycoon Igor Ashurbeyli. Asgardia is adamant about creating an elected parliament to give regular Asgardians a say in how things are run, another trapping of government that Asgardia hopes would help it join the UN (a prospect space law experts consider pretty nuts.)

Dr Igor Ashurbeyli is the main reason proponents of Asgardia believe these fantastical plans can actually become reality. The mustachioed 54-year-old engineer started Asgardia in 2016 and previously oversaw the development of Russia’s feared S-400 anti-aircraft missile system.

While he funds almost the entirety of Asgardia’s considerable expenses, Ashurbeyli denies being a billionaire, as some outlets have reported; he has valued his industrial company at somewhere around $US200 million ($260 million). Ashurbeyli is not exactly a model statesman. In a mostly unflattering profile of Ashurbeyli, Russian and English language media outlet Meduza said he “behaves like a spoiled child” who refuses to answer difficult questions, despite having a human skeleton on display by his office to show visitors that he has no skeletons in his closet.

His personal website’s blog also includes insights such as “Asgardia is a cosmic Columbus of the 21st century!” and “Russia needs altruists and romantics, not pederasts and petty thieves.” In the later quote, Ashurbeyli used the plural of the word “пидораст” – an awkward mishmash of “педераст” which translates to “pederast”, and “пидорас”, a word regrettably used in Russia as a homophobic slur. After a request for clarification, NGO Asgardia’s director Lena De Winne argued that Ashurbeyli implied “the colloquival [sic] meaning” of the slur as “an expression of attitude” closer to “motherfucker”, and referred me to the Declaration of Unity p.4, which states: “All citizens of Asgardia are equal, regardless of their Earthly country of origin, residence, citizenship, race, nationality, gender, language, or financial standing.” Notably, this section doesn’t explicitly forbid discrimination against LGBT people.

Ashurbeyli, who anointed himself Asgardia’s “Head of Nation” last year, has repeatedly stated that he wants Asgardia to be able to run itself in a democratic manner, even joking to Meduza that he’d like to retire to the French Riviera like Putin after his first five-year term is over.

Yet Ashurbeyli was also described by Meduza as a staunch monarchist who claims that when he was young, it was prophesied he would one day serve a tsar. He also has other projects beyond Asgardia, such as funding the construction of Orthodox cathedrals across Russia, a place where the old monarchy and religion are closely linked.

Last year, Ashurbeyli sparked significant controversy for imposing a constitution that declared Asgardia a constitutional monarchy rather than a republic, hence the term “Space Kingdom”.

The constitution, which included details on everything from Asgardia’s future unit of currency (the SOLAR) to a goal of establishing a single Asgardian language, had many Asgardians worrying that it handed Asgardia’s head of nation too much power. For example, Asgardia’s leader was given the right to dissolve parliament and significant control over the powerful Supreme Space Council, a kind of advisory body which plays a key role in determining who the next head of nation will be. Ultimately, the constitution passed with a wide majority; when it was voted on, there was no formal way to vote “no” – it was claimed that visiting the voting page and not clicking “yes” counted as a “no”.

But even after it passed, the constitution continued to haunt Asgardia’s progress. One of the major reasons Asgardia’s first parliamentary elections have been so bumpy since they started last September was a bizarre clause in the constitution stipulating that all members of parliament had to be between the ages of 40 and 80. The move effectively excluded most Asgardians from running (the average Asgardian is about 31 years old, according to NGO Asgardia.) In response, many Asgardians backed a referendum to lower the minimum age to 25. “Allowing everyone 25 years old and older to run and be elected allows a greater voice for the citizens and will allow a full Parliament which is fundamental to UN recognition and nation building,” wrote one Asgardian in a widely-circulated petition. “This issue has also caused a lot of strife within the community.”

To the disappointment of many, the restrictive age provisions for parliamentarians were kept. In a compromise of sorts, Asgardians below the age of 40 could run to be shortlisted for potential and unspecified “government” positions. However, the number of votes one receives as a government candidate makes no real difference as to whether they will be selected, explained NGO Asgardia director Lena De Winne. The move was quite confusing: I chatted with one Asgardian below the age of 40 who thought he was running for parliament when he was actually in the vaguely-defined “government” category.

A significant number of eager middle-aged Asgardians thus signed up to run for the world’s first space parliament. There were 150 seats up for grabs across 13 separate districts separated by language that Asgardians are automatically assigned to. The larger the district’s population, the larger its seat allocation; for example, the English district is Asgardia’s largest with 64 seats. The elections attracted a wide range of candidates, from an American gynaecologist who photoshopped his face onto the body of an astronaut to an Italian man advocating a “space nation for the Goths!” or a Turkish man advocating Istanbul be declared the centre of Asgardia. Other candidates offered up policy proposals such as a Universal Basic Income and a host of wildly contrasting plans for Asgardia’s first space station. Overall, the elections did garner genuine enthusiasm from people who hoped, in their own way, to escape Earthly politics and be part of something radically different.

But partly because so many candidates were initially allowed to run with little effective vetting, numerous issues occurred. Certain candidates had exceedingly vague platforms or seemed like outright fakes, while some reportedly spammed other candidates for votes in exchange for their own. Asgardia’s Central Electoral Commission attempted to fix such problems by requiring candidates to pay a €100 ($160) fee to run, but the snap decision led to real candidates complaining that they couldn’t afford it on short notice or that it was wrong on principle. “The fee is bullshit. Period. They don’t need any money. This is just a fundraiser disguised as a supposed fee,” one Asgardian commented on Facebook. “I hope no one pays, and it blows up in [Ashurbeyli’s] face.” The CEC eventually allowed candidates to sign a promise that they would pay the fee later and made it easier for candidates to raise donations online.

None of this was helped by Asgardia’s clunky website, which is still in beta mode and has loading times reminiscent of the mid-2000s; it even had to be taken down for upgrades the day before the final round of voting started. Because the website has so many sections – from a detailed FAQ to a page for the official “congratulatory letters” Ashurbeyli regularly sends to world leaders such as Xi Jinping and Angela Merkel on their latest elections – I initially struggled to find the main page for Asgardia’s elections, and when I did, the system left much to be desired. For example, there’s no way to privately message candidates who you haven’t “friended” yet, and the candidates’ platforms appear like little more than blog posts. Partly for this reason, much of the actual campaigning for Asgardia’s elections took place on various Facebook groups, and some candidates even built their own campaign websites.

But it was vetting-related problems that caused much of the chaos, and these became even more apparent after the final round of voting wrapped up on March 9. Some Asgardians who had successfully run for office were freaked out after they weren’t included in a preliminary list of candidates who’d met the minimum electoral requirements to win. Amad Ahmed, a 45-year-old Iraqi engineer who was at one point the second most popular candidate in Asgardia’s Arabic district, claimed he’d paid Asgardia’s fee and provided all the necessary documents but didn’t end up on the preliminary list. He claimed to have received no clear explanation of whether he’d make it or not. “I don’t know exactly what’s the problem, they said it’s not the last decision but we don’t know,” he said. “We have to have some information.” (De Winne later explained that Amad Ahmed’s registration payment was lost because he sent it via Western Union instead of PayPal.)

The messiness of Asgardia’s electoral system led to some believing that it was rigged. In some districts, several obscure candidates with vague policy platforms popped up right before registration closed and made it to the preliminary list despite being mostly unknown in Asgardia’s tight-knit political community. Eyebrows were raised particularly high in the French district when its allocation of parliamentary seats was mysteriously increased from four to six at the last minute, a move that allowed two candidates from Nice with Russian-sounding last names obtain fifth and sixth place. In the Turkish district, six similarly obscure candidates from Azerbaijan – a country where people speak a language similar to Turkish and that is also the birthplace of Igor Ashurbeyli – signed up in some cases literally hours before the registration deadline and still made it to the preliminary list of candidates. Partly because these seemingly sketchy candidates had Russian-sounding names or were from the former USSR, some Asgardians even theorised they were spies sent by Asgardia’s Soviet-born leader himself to infiltrate parliament. “I wonder if it’s not manipulation from the top,” one leading candidate told me anonymously. “I don’t know if [Ashurbeyli] wants a parliament or a Duma.”

While I didn’t get any replies from these supposed spies by reaching out to them, Asgardia’s management flatly denied the allegations. NGO Asgardia director Lena De Winne said some candidates may have signed up at the last minute due to simple human nature, while the sudden increase in seats in the French district was due to a growth in its population.

“We have activists who run spontaneous social gatherings,” she wrote in an email. “There have been cases in the past when we had brief surges in growth of population from one region which we could not understand.”

Moreover, De Winne denied that Asgardia’s founder had dictatorial ambitions or was seeking to be sabotage parliament. She pointed out that he had promised to leave after his first five year term and suggested that some degree of direct leadership was necessary to nurture Asgardia’s growth in its early stages. “In my personal experience, people who are the most outspoken critics are people who generally find something bad almost in everything,” she added.

Ross Cheeseright, a 34-year-old Asgardian from the UK, said the real problem with the elections were more mundane, such as the buggy website and snap decisions. Such issues were to be expected in such a fledgling project, but he hoped they could be fixed in the future. “Although there was a lot of passion and good intentions it definitely needed a more robust process,” he said. “I would like a commission under parliament to look into this and make the next elections more robust.”

The final list of the official winners of Asgardia’s elections was released on April 1. Amad Ahmed, the candidate who’d worried about getting nixed, ended up making the cut, while the two supposed infiltrators in the French district did not. The six last-minute candidates from Azerbaijan in the Turkish district, however, did make it. But all the issues that plagued the election haven’t been ironed out yet: A one month “by-election” period was announced from April 16 to May 16 to so that “all candidates could meet the CEC’s requirements in a timely manner”. That would put a final end to the elections a few weeks before the first assembly of Asgardian parliamentarians takes place at an all-expenses-paid conference in Vienna in June.

Ariadne Figueroa, a 59-year-old Mexican radio station worker and occasional science fiction author who won a seat in the Spanish district, said she may go to Vienna if it is indeed paid for. It would be her first time in Europe, but her goals as an Asgardian parliamentarian are bigger than that: She plans on helping protect the Earth by getting rid of space junk orbiting the planet. Being an MP of the world’s first space parliament isn’t something to be taken lightly, and it makes her “flattered and nervous at the same time”. “Yes, [it’s] a great responsibility,” she said.

Full disclosure: I joined Asgardia to report this piece.