Around 74,000 years ago, a massive caldera erupted on the Indonesian island of Sumatra, triggering a prolonged and devastating volcanic winter. Scientists have speculated that the Toba eruption pruned back human populations to a considerable degree, but new research published today suggests at least one group of humans living in southern Africa not only managed to survive the event – they actually prospered. The Toba eruption, as we’re learning, wasn’t nearly as bad for humans as we thought – and it may not have produced a volcanic winter at all.

A satellite image of Lake Toba, Indonesia. Some 74,000 years ago, this caldera exploded, hurtling thousands of tonnes of ash into the atmosphere. Photo: NASA Landsat

The Toba supervolcanic eruption – the most powerful eruption to happen in the past two million years – hurtled thousands upon thousands of tonnes of ash and other aerosols into Earth’s atmosphere. Temperatures around the Earth plummeted, unleashing what scientists have assumed was a volcanic winter that lasted somewhere between six to 10 years, and possibly inducing a cooling period that lasted nearly a thousand years. With so much debris in the atmosphere, sunlight barely touched the Earth’s surface, threatening entire species with extinction.

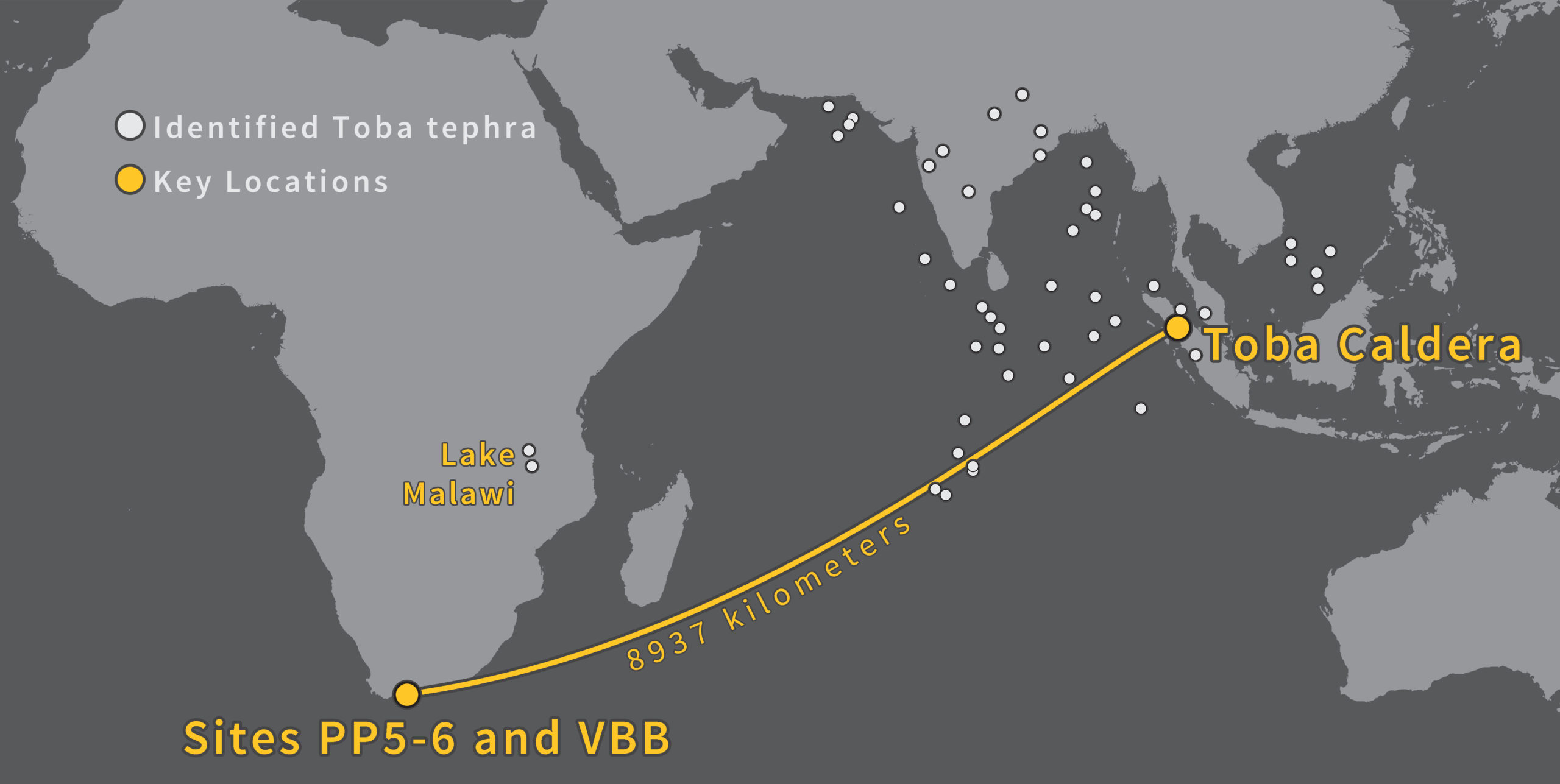

Back in the 1990s, scientists theorised that the lingering effects of the Toba eruption created a population bottleneck, reducing the size of Homo sapiens to 10,000 individuals from an effective population of about 100,000. No doubt, the environment would have literally changed overnight for human hunter-gatherers living in Africa and Eurasia, forcing them to adapt to the changing conditions. As new research published in Nature shows, there was at least one pocket of humans living in southern Africa, some 9000km away from the site of the eruption, that managed to survive this calamitous period in geological history. And in fact, as the authors of the new study point out, they didn’t just survive – they thrived.

It’s very possible that this particular band of humans was at the right place at the right time, allowing them to survive the ensuing volcanic winter. But other researchers say it’s yet another sign that the effects of the Toba eruption wasn’t nearly as bad as we’ve been led to believe. The so-called “Toba Catastrophe Theory”, as it’s called, may actually be a myth. What’s more, the volcanic winter may not have even happened.

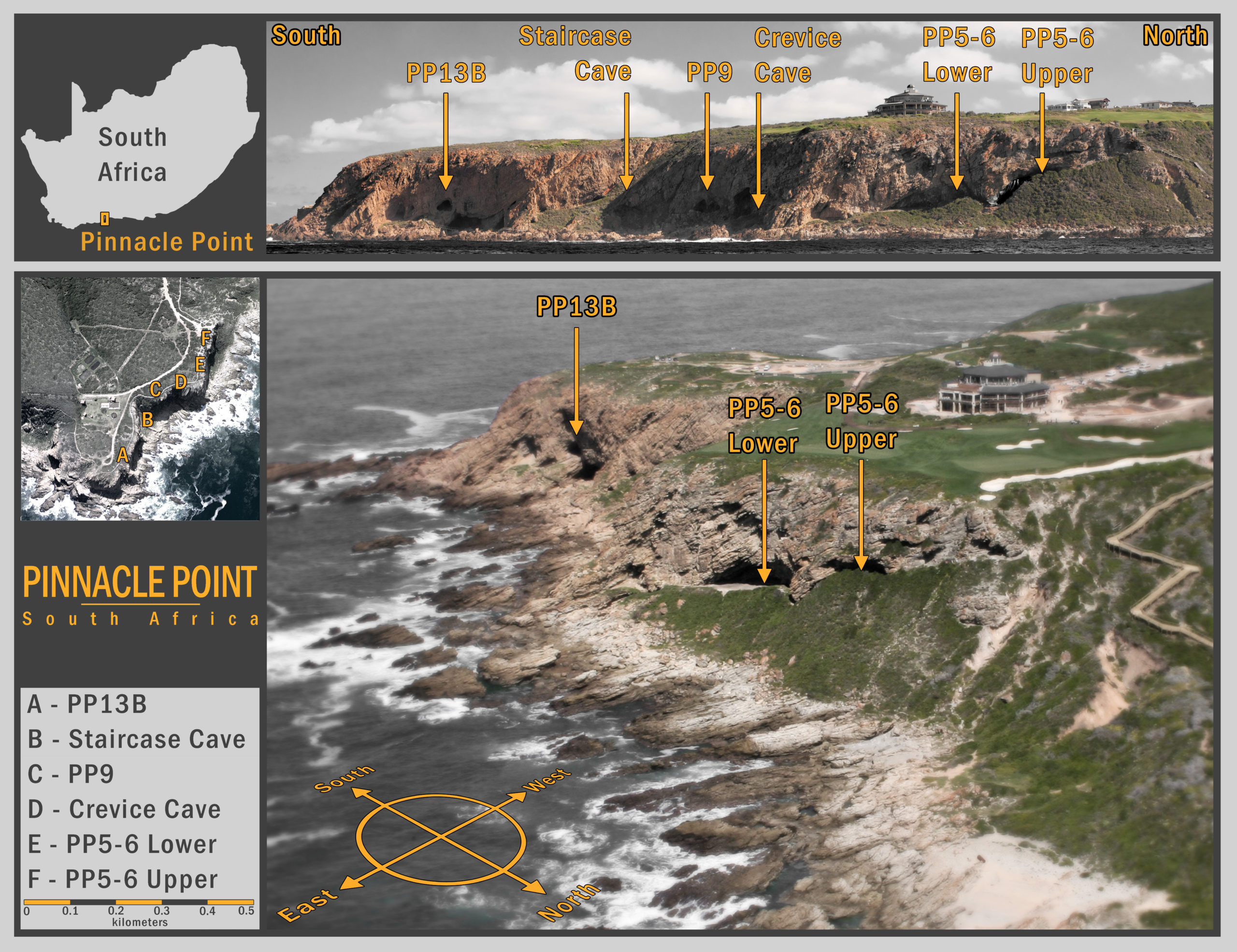

The Pinnacle Point caves. Image: Erich Fisher

The lead authors of the new study, Curtis W. Marean from Arizona State University and Panagiotis Karkanas from the American School of Classical Studies in Athens, Greece, uncovered evidence of human habitation at two excavation sites along the southern coast of South Africa: The Pinnacle Point rockshelter, where humans lived, worked, ate and slept, and the Vleesbaai dig, a former open air site where humans, possibly those from the Pinnacle Point caves just 10km away, sat in a small circle making stone tools.

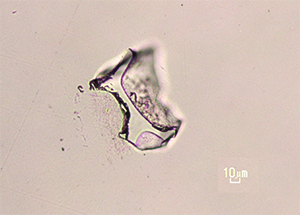

This volcanic glass shard from the Toba volcano was found at an archaeological site nearly 9000km away at Vleesbaai, South Africa. Image: Rachael Johnsen

Shards found at these two locations link these sites to the same point in time, as established by previous dating efforts (these caves have been studied for nearly 20 years). But Marean and Karkanas also found traces of the Toba eruption at these sites in the form of microscopic pieces of glass known as cryptotephra, which was intermixed with the rock and gas blasted out from the supervolcano. Using a new dating technique known as optically stimulated luminescence (OSL), in which scientists can tell the last time a grain of sand was exposed to sunlight, the researchers were able to corroborate the previously established date of the sites, and also show that humans occupied these two locations during and after the Toba eruption.

By studying the archaeological items found at the sites, including stone artefacts, bones and other cultural remains, the team was able to create a model of the site, showing continuous – and even increasing – human occupation during the time of the Toba eruption. No evidence was found to indicate that the eruption impacted their daily lives.

Map showing the distance between Toba and the South African sites. By tephra, the scientists are referring to rock fragments, ash and other particles ejected by a volcanic eruption. Image: Erich Fisher

“Many previous studies have tried to test the hypothesis that Toba devastated human populations,” said Marean in a press release. “But they have failed because they have been unable to present definitive evidence linking a human occupation to the exact moment of the event.”

The area may have served as a kind of “refugia” – a place where humans sought shelter from the degraded environmental conditions. These early humans managed to survive, argue the researchers, by taking advantage of their proximity to coastal waters. The hunter-gatherers likely subsisted on seafood, which is less vulnerable to a prolonged volcanic winter than terrestrial plants and animals. It’s now the only known example of Toba-era survival in the archaeological record, so the authors of the new study are hoping that other teams will be able to uncover similar evidence of survival elsewhere in Africa, and possibly Eurasia.

“I do think this is wonderful work,” Martin B. Richards, a University of Huddersfield archaeogeneticist who was not involved with the new study, told Gizmodo. “It confirms that the Toba eruption impact was worldwide and that Africa harboured refugial groups of early modern humans who survived the resulting climatic impact and went in to settle the whole world in the following millennia.”

Richards points out that other humans living in Eurasia were heavily hit by the climate effects of Toba, and that some of them, like the Neanderthals, survived until modern humans arrived considerably later.

In a related study published this past weekend in the Journal of Human Evolution, a team led by Chad Yost from the University of Arizona analysed charcoal records and other evidence found at Lake Malawi in eastern Africa. Like the other researchers, they linked samples embedded with cryptotephra to the Toba eruption. But this study was more geological than archaeological, with Yost’s team concluding that the volcanic winter was not as bad as scientists have assumed.

“We find no support for the Toba catastrophe hypothesis and conclude that the Toba supereruption did not produce a six-year-long volcanic winter in eastern Africa, cause a genetic bottleneck among African [anatomically modern human, i.e. Homo sapien] populations, or bring humanity to the brink of extinction,” conclude the authors in that study.

Given the similarities of the two new studies, we contacted Yost to see how this latest research relates, and how our conceptions of the Toba eruption might be changing.

“The datasets from our research and the Nature paper complement one another and together indicate that the Toba supereruption had little effect on the climate of Africa and the humans who were living there,” Yost told Gizmodo. “Where the two studies diverge has to do with interpreting the magnitude of climate change from the Toba eruption.”

Yost says Marean and Karkanas failed to cite the most recent Toba eruption climate model showing minimal cooling in Africa, as well as other geological studies suggesting climate models have overestimated the amount of erupted atmospheric aerosols by one to two orders of magnitude.

“We conclude, based on empirical evidence, that there was no volcanic winter,” he said. “In contrast, the authors of the Nature paper actually invoke a ‘decade or more of volcanic winter’ to bolster their hypothesis that South Africa was a refugia and the sole source for modern human populations after the eruption.”

John Hawks, an anthropologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, agrees with Yost, saying the Toba eruption was probably a major event, and early humans probably noticed – but it did not have the catastrophic impact that some scientists believed.

“The way I look at this, we have many lines of evidence about Earth’s history, including the fossil record, archaeology, ashfalls from ancient eruptions, ice and deep sea cores,” Hawks told Gizmodo. “We’ve learned more and more about the kinds of events that have happened. It’s human nature to want all of them to match up into a single series of cause and effect.”

But the human past was not that simple, he says.

“Some big events like Toba happen to be obvious to us in geology,” said Hawks. “But they were actually fairly small in the scheme of things. Hominin populations were resilient and able to adapt to the kind of small-scale climate changes caused by eruptions.”

[Nature]