On May 25, 1798, the HMS DeBraak was entering Delaware Bay when a squall struck without warning. The British ship that originally belonged to the Dutch capsized and sank, taking 34 sailors and a dozen Spanish prisoners down with it. Rumoured to contain a hoard of gold and jewellery, the DeBraak became a popular target for treasure hunters in the years that followed. The wreck was finally discovered in 1986, lying under 25m of water at the mouth of the Delaware River. The team who found the ship attempted to raise it from its watery grave, resulting in one of the worst archaeological disasters in modern history. The event precipitated the passing of long-overdue laws designed to prevent something like this from ever happening again.

“DeBraacle”

Cannons recovered for the wreck being carefully stored in temperature and humidity controlled conditions by Charles Fithian and his team of the State of Delaware Historical and Cultural Affairs.Photo: Anthony Green (The Filey Bay Research Group)

Soon after the wreck of the DeBraak was found, treasure hunters speculated that it contained riches to the tune of $US500 ($647) million, even though no evidence existed to support the claim. The team who made the discovery formed a company called Sub-Sal Incorporated to conduct a salvage operation. Its divers eagerly scoured the wreck, pulling up a gold ring belonging to the ship’s captain, belt buckles, a cannon, a long-barreled pistol, two bottles of rum, scabbards, toothbrushes (sans bristles), a pewter spoon, and hundreds of other items. The divers also recovered more than a hundred gold and silver coins, which they used as collateral for an $US85,000 ($109,947) loan to keep the project afloat.

Indeed, Sub-Sal co-owner Harvey Harrington and his partners were quickly losing money, and they started to believe that salving the wreck by hand was a waste of time. After months of diving, and failing to find the hoard of gold bullion and jewels, the owners hatched a plan to raise the ship to the surface where it could be examined under controlled conditions. Archaeologists hired for the project were assured that the ship would remain intact, its precious cargo unperturbed.

The salvors estimated that they had recovered a mere 20 per cent of what the wreck had to offer, and that the good stuff was either inside the ship or had drifted through the decaying hull and into the mud underneath. Either way, removal of the ship was key; crews could then dredge the estimated 2,600 cubic yards of sand and muck from the seafloor, and use high-pressure water jets to filter any artifacts from the dense sediment.

A crane was installed alongside a barge above the wreck. Divers placed thick sling cables around the hull and a steel-beamed cradle next to the ship. The idea was to place the ship onto the cradle and lift it to the surface without tipping it over and spilling its cargo. A wire mesh was placed at an overhang near the bow to catch any falling artifacts.

Inside face of ship’s timbers. The hull undergoing spray treatment by Charles Fithian and his staff at the State of Delaware Historical and Cultural Affairs.Photo: Anthony Green (The Filey Bay Research Group)

At 9:00 pm on the evening of August 11, 1988, the effort to raise the ship began. At the last minute, Sub-Sal organisers decided to abandon their plan to place the ship on the steel cradle, opting instead to lift it up by the cables alone. As the crane raised the DeBraak, and as it was freed from the ocean bottom where it had been resting for hundreds of years, a friction brake snapped. After an agonizing delay to perform repairs, the DeBraak was finally lifted from the water — but the cables had cut into the ship’s hull like a chainsaw. Water, mud, solid objects – even a cannonball – poured from the holes and back into the ocean.

The remnants of the shattered boat, namely a large section of the starboard hull, were placed on an auxiliary barge. Afterwards, the New York Times declared the effort to raise the DeBraak a success, but the archaeologists hired for the project were furious. They accused Sub-Sal of creating a publicity event, saying valuable artifacts — including a dozen intact barrels — had been lost because the ship hadn’t been raised properly. An estimated 800 cubic feet of silt poured from out of the hull, ruining an opportunity for the archaeologists to study the ship’s artifacts in their original position. The incident was later referred to as an “archaeological disaster,” and dubbed the “DeBraacle.”

But like any classic tragedy, this tale offered absolution in the form of long-overdue legislation.

The same year of the DeBraak incident, and in consideration of the thousands of US wrecks that had been salvaged, and often ruined, by treasure hunters in the 1970s and 1980s, the United States enacted the Abandoned Shipwrecks Act (ASA). The law arrived at a time when recent advances in technology, including robotic subs and 3D radar scans, made many of the wrecks accessible to looters, treasure hunters, and others capable of causing damage.

The ASA worked to protect historic shipwrecks like the DeBraak, but it didn’t cover military wrecks, which were considered the property of the country that commissioned the sunken craft. Again, it took an international incident for the laws to catch up — one with its origins in the Second World War.

Sunken monuments

In the early morning hours of December 7, 1941, the US minesweeper Condor spotted a submarine periscope just outside of Pearl Harbour, as noted in a historical NOAA National Marine Sanctuaries account of this largely forgotten incident. The Condor alerted the crew of the USS Ward, which was nearby. After spotting the sub’s periscope, the Ward’s captain ordered an attack, sinking the vessel. Immediately afterwards, the Ward sent a report of the attack to US Naval Command, but officials refused to believe it was a Japanese sub. What Naval Command didn’t know, however, was that the high-tech, top-secret sub — a Japanese Ko-hyoteki-class, two-man mini-submarine — was one of five such vessels in the area, each deployed by a larger Imperial Japanese Navy submarine lurking off the coast of Oahu, Hawaii.

At 8:00 am, all hell broke loose as the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour began in earnest, killing over 2,400 American servicemen and injuring nearly 1,200. The actions of the USS Ward on that fateful morning have gone down in history as representing the first shots fired by the US in the Second World War.

In the years and decades following the war, some sceptics refused to believe that the Ward had actually sunk the mini-submarine. The debate was finally put to rest when the wreck was discovered by researchers from the University of Hawaii’s Undersea Research Laboratory in 2002. The mini-sub was found in remarkably good condition under 335.28m of water, just a few miles from where the Ward reported the encounter.

The question of what to do with the historic wreck – and who owned it – presented serious challenges to US authorities. Did it belong to Japan? The United States? Both? And who would be responsible for preserving and protecting the sunken relic?

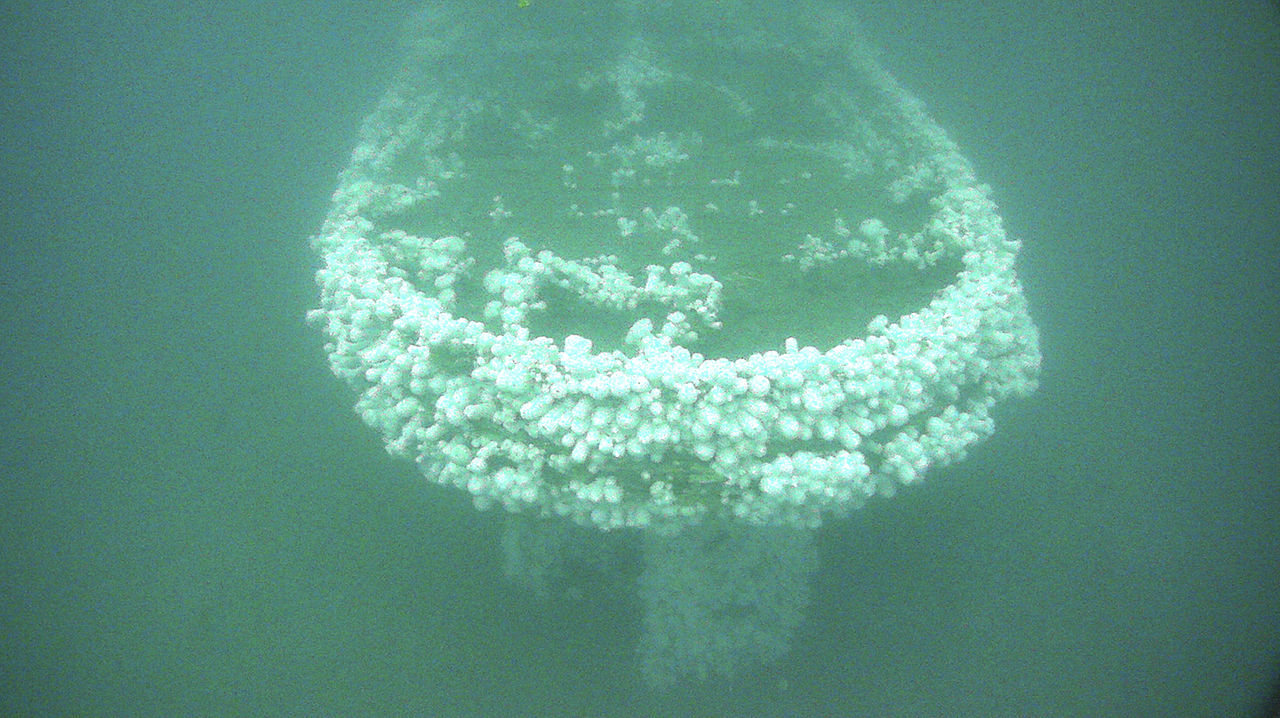

Stern view of the shipwrecked USS Conestoga (AT-54) colonised with white plumose sea anemones. On March 23, 2016, NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries (ONMS) and the U.S. Navy announced the discovery of the wreck of USS Conestoga (AT-54) within the waters of Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary in California. The discovery by the ONMS Maritime Heritage Program solved a 95-year-old mystery. Conestoga sailed from San Francisco Bay in March 1921 and vanished with 56 men. Until 2016, what happened, and where the wreck and its crew lay, had been described as one of the top maritime mysteries in U.S Navy history.Photo: NOAA Office of National Marine Sanctuaries

Ole Varmer, an attorney adviser with the International Section of NOAA’s Office of General Counsel, said the ultimate goal was to protect the preservation of the largely intact sub, which most likely contains the remains of two Japanese sailors. Moreover, by protecting the sub, the US was doing its part to preserve the integrity of history.

“Statues and monuments are fine, but the story is told by its makers, and it’s more important to preserve actual historic sites,” Varmer told Gizmodo, suggesting that wrecks be left – and even possibly preserved – where they were found. “Some of the sites of the atrocities of WWII are being preserved so that people will always remember that loss of life, and help rebut the Holocaust deniers.” Similarly, he notes that “the on-site preservation of the USS Arizona and the wreck of the Japanese mini sub in Pearl Harbour help preserve primary evidence of this historic event, and respectfully remember the loss of those sailors from both sides of the war.”

In the case of the Japanese mini-sub, and in the absence of a coherent, pre-determined agreement, the US devised a kind of legal kluge to deal with the situation.

“Through an exchange of diplomatic notes, Japan agreed that the United States owned the mini-sub,” Varmer told Gizmodo. “The US then intervened in a case against the sub, as under salvage law owners may approve or deny any salvage services. In this case, the US was granted a permanent injunction against any salvaging of the sub without authorization. The US also promised the government of Japan that it would treat the wreck with respect and never authorise salvage without consulting it first.”

Because of the confusion and uncertainty generated by this incident, and because there are nearly 1,700 US military wrecks strewn around the oceans of the world, the US enacted the Sunken Military Craft Act (SMCA) in 2004.

The US Navy’s Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC), a branch of the Navy responsible for preserving naval history, says the SMCA “preserves the sovereign status of sunken US military vessels and aircraft by codifying both their protected sovereign status and permanent US ownership, regardless of the passage of time.” This means all US military wrecks are the property of the US government, forever and for all time. What’s more, the SMCA “protects sunken US military ships and aircraft wherever they are located, as well as the graves of their lost military personnel, sensitive archaeological artifacts, and historical information.” So a US military wreck that’s located in the South Pacific Coral Sea is just as much the property of the US government as a wreck located a mile off the coast of North Carolina; the SMCA protects both sunken US and foreign craft in American waters, which includes all internal waters, territorial sea, and the contiguous zone up to 24 nautical miles off the US coast.

Paul Taylor, a spokesperson for NHHC, says US ships were always regarded as government property after sinking, but the absence of a coherent and binding law made preservation and protection difficult.

“Though retaining their status as government property, a series of US Navy shipwrecks were disturbed without authorization or looted in the decades leading up to the SMCA,” Taylor told Gizmodo. “In a number of court cases, the US government reasserted its title to these crafts, but this was only after a site had been irreversibly disturbed and/or artifacts recovered.”

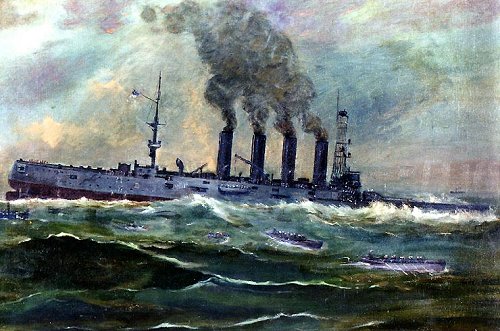

“The Sinking of USS San Diego”. A 1920 watercolor of the sinking of USS San Diego in 1918. It shows the ship sinking off Fire Island, New York, after it was torpedoed by a German submarine.Image: Francis Muller

A good example is the wreck of the USS San Diego, the only major warship lost by the US Navy during the First World War. Its final resting place is 16km off the shore of Fire Island, New York, below 33.53m of water. The ship capsized after an explosion tore through its hull, killing six sailors. Prior to the SMCA, the wreck was a popular target for professional and recreational divers, who retrieved dinnerware, lanterns, bullets, an artillery shell, and other objects (some of which were donated to museums). Divers even tried, unsuccessfully, to raise the ship’s 16,783kg bronze propeller. According to the Navy, more people have died diving to the wreck than during the sinking itself.

A similar thing happened to the wreck of the USS Nina, which sunk in 1910 off the coast of New Jersey. The Washington Post covered the news of its discovery in 1978, writing:

[Divers] have been salvaging bits and pieces from the Nina since the beginning of the year. So far they have hoisted the anchor, six brass portholes, the ship’s 113kg brass bell with the works “USS Nina” etched on its side, and several glass skylights that worked as prisms to distribute light below the Nina’s deck.

Freeman, 54, has also found numerous personal effects of the ship crew, including a gold pocketwatch and turn-of-the-century diving gear, such as lead helmets and 14kg diving boots.

“We also got a leather wallet that was beautifully preserved underwater,” he said. “We brought it up and put it in a bucket of water on my boat, but a cabin boy thought it was junk and tossed it overboard.”

More extreme examples can be found elsewhere — episodes that demonstrate the need to protect sunken military vessels in foreign waters. In 2016, the Dutch Navy discovered that two of its warships lost in a historic naval battle in 1942 had vanished from the bottom of the Java Sea. Similar things have been happening off Borneo. These ships were apparently scavenged for raw materials such as steel, aluminium, and brass. The scavengers, often posing as fishermen, use explosives to tear the ships apart and then raise the bits and pieces to the surface. Propellers made from phosphor bronze can fetch as much as $US2,500 ($3,234) per ton. Recently, it was revealed that shipwreck scavengers dumped the remains of Dutch and British sailors in a mass grave near the port of Brondong in east Java, Indonesia.

In addition to protecting military vessels as solemn war graves, Taylor says there’s increasing interest in conducting research on sunken military craft and a need to provide the public with a means through which to access these sites.

“The SMCA, therefore, put in place the prerequisites for a permitting program that encouraged archaeological, historical, and educational research on sunken military craft, while also reinforcing that these sites could not be disturbed without authorization by putting in place stricter civil penalties and violation provisions,” he said. Since the passage of the SMCA, the US Navy hasn’t had to prosecute any person or group for illegally disturbing a sunken military vessel, according to Taylor. But as the episodes in the Java Sea and Borneo point out, laws are only effective when they’re enforced; the US has to depend on other countries to defend wrecks outside its waters.

Unexpected threats

Needless to say, not everyone agrees with the rules laid out by the ASA and the SMCA. Some divers and salvors think it’s a huge waste for these wrecks to lie at the bottom of the sea, their precious artifacts wasting away. Moreover, many don’t believe they’re imparting any harm or indignity onto the wrecks, and that other groups and individuals are inflicting far more damage.

“I have debates with commercial salvors on a regular basis, and they always raise how bottom trawling can do more destruction than proper research and recovery, and I agree with them,” Varmer, the NOAA legal expert, told Gizmodo. “Those who are doing bottom trawling don’t intend to run over a wreck, but it inadvertently happens sometimes — and that’s something that the US government and fishermen could work together to improve upon.”

But other threats are emerging as well, particularly as the ocean floor opens up to mining, energy development in the form of oil and gas extraction, and the construction of wind turbines.

“This is an area where there needs to be compliance with both the US National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) and the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA),” said Varmer. The NHPA is designed to preserve historical and archaeological sites in the United States, while NEPA requires federal agencies to evaluate the environmental effects of potential work prior making any decisions.

“If we’re doing a good job, in the planning of the project we should be identifying historic properties to avoid or minimise impacts. If they’re unexpectedly found in excavation, we should put the destructive activities on hold just like we do on land when we discover graves and other historic sites,” said Varmer. “The project managers should avoid or minimise the destruction of these historic properties. This would include the conduct of archaeological work that needs to be done to preserve information from sites that may end up being destroyed by the project.” He says this is a sensible strategy for balancing economic development with the preservation of US heritage.

Matters of dispute

And then there’s the matter of historical interpretation.

Back in 2016, Marine salvage firm Global Marine Exploration (GME) discovered scattered evidence of a potentially historic wreck near Cape Canaveral, Florida. The discovery of three French bronze cannons and a French granite monument adorned with the French king’s coat-of-arms led GME chairman and CEO Robert Pritchett to conclude that he’d uncovered traces of the Jean Ribault wreck — a doomed expedition to Florida that resulted in the sinking of two ships in a storm in 1565.

Armed with Florida permits, Pritchett’s team explored several areas in the region in May and June of 2016, but GME is now waiting for a Florida court to determine who has rights to recover artifacts from the wreck. It’s an important decision, as the ships represent one of the earliest wrecks dating back to the European settlement of the New World. What’s more, there’s a lot of money to be had from the artifacts; the ornate brass cannons are estimated to be worth more than $US1 ($1) million each (and there may be as many as 22 of them).

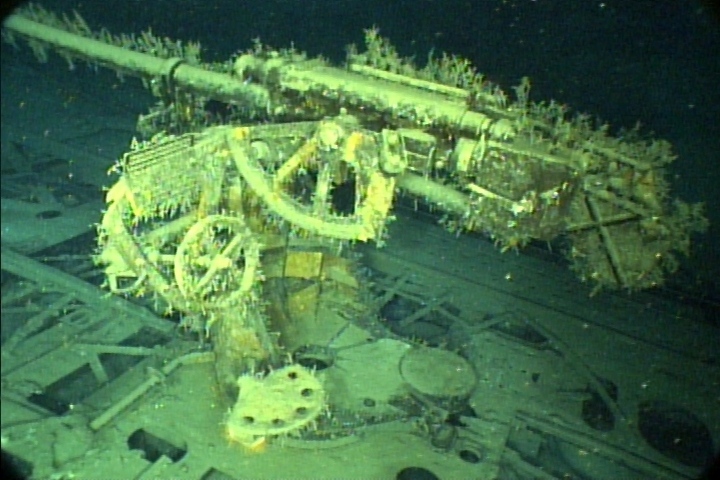

A deck gun of the sunken German U-boat U-166.Photo: NOAA’s Maritime Heritage Program; Collection of LCDR Jeremy Weirich, NOAA Corps

To complicate matters, the French government has entered into the fray, claiming that it maintains ownership of the artifacts under the US Sunken Military Craft Act. France says the military act applies because Ribault’s ships were attempting to transport French soldiers to attack a Spanish colony at St. Augustine, but the ships didn’t make it on account of the storm. These circumstances, France argues, qualify the wreck and its contents to fall under the SMCA. As Live Science reported last year, the state of Florida is supporting France in its claim for ownership, while also claiming that GME violated terms of exploration permits — a claim that GME denies.

Pritchett, on the other hand, has told the Florida court that the artifacts don’t belong to Ribault’s fleet, or any French ship for that matter. In his interpretation of history, the cannons and the monument were plundered during a raid in 1565 and were onboard Spanish ships heading for Cuba when they sunk off the Florida coast. Consequently, Pritchett believes France has no sovereign right to the ships.

This case is still in the courts, but it illustrates the challenges of balancing marine preservation with archaeology and the collection of valuable historical artifacts. (Gizmodo contacted Robert Pritchett, and he declined an opportunity to comment.)

Conflicts of interest

Clearly, a tension exists between commercial divers and the US government. Some wreck divers, like John Chatterton, the former co-host of the History Channel’s show Deep Sea Detectives, don’t believe that government should even be in the archaeology business.

“If they want to regulate, or oversee in a reasonable fashion, and make sure sites under their control are dealt with responsibly, great,” Chatterton told Gizmodo. “When NOAA does exploration and salvage using tax dollars, they are competing against commercial salvors. If the government is making the laws, and then acting as competition to salvors, there is clear conflict of interest, and I can’t imagine anyone thinking salvors will get a fair deal. It is corrupt.”

What’s more, Chatterton believes the SMCA allows the US government to act hypocritically – particularly on the issue of marine gravesites.

“Sailors’ graves are off limits to salvage and exploration, due to ethical issues,” he said. “Then again, ethics are different when the government was involved on projects like the H. L. Hunley and the USS Monitor, both of which brought sailor’s remains to the surface.”

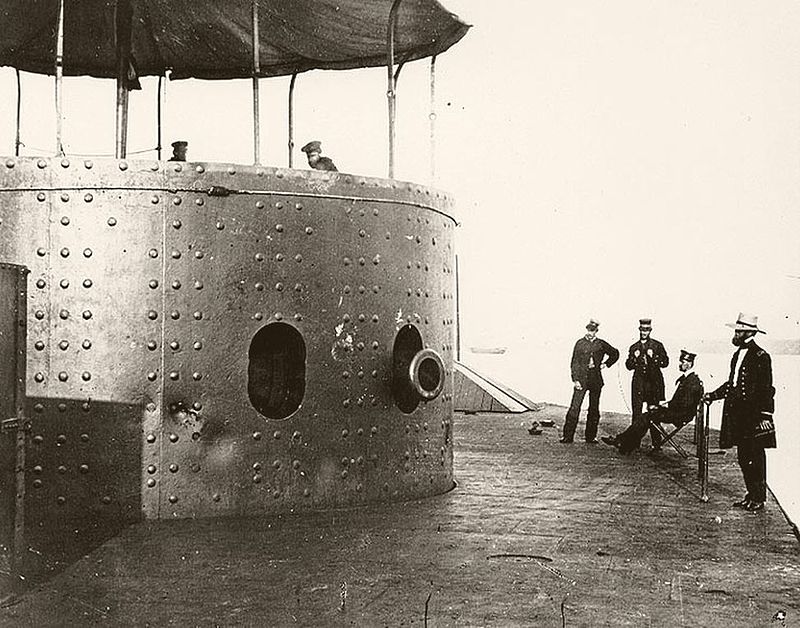

USS Monitor engaging CSS Virginia, March 9th, 1862. A lithograph signed “Jo Davidson”.Image: United States Library of Congress

The Hunley was a Confederate sub that sunk during the Civil War, and the Monitor was a Union ship that also sunk during the war. To be fair, these sunken vessels were pulled from the water prior to the introduction of the SMCA, but Chatterton said he’s speaking “in terms of ethical standards imposed by the law,” which he feels “the government and academics have only followed selectively to date,” adding that he’s “all for protecting sailors’ remains.”

James Delgado, a marine archaeologist and vice president of SEARCH, thinks Chatterton is conflating salvaging with treasure hunting.

Monitor on the James River, Virginia, 1862. Officers on deck.Photo: Unknown photographer (United States Naval History & Heritage Command)

“Salvage is an ancient, honorable business that works to retrieve or recover and return goods ranging from ships to cargoes to the stream of commerce,” Delgado told Gizmodo. “In my time, I have seen that range from oil trapped in sunken ships, canned fish, containers, and of course, vessels of various types that have sank and which can be raised. That includes fishing boats and tugs, barges, and the Costa Concordia. I know and have many friends in the marine salvage business.”

The term “salvage,” says Delgado, has been applied to treasure hunting, but he says that’s an inaccurate assertion in most cases.

“A vessel that has been on the bottom for hundreds of years is not a candidate for ‘salvage’ but for archaeological recovery if it is of archaeological significance — that is, if excavating it can add to our understanding of the past,” he said. “In terms of the assertion of the ‘government’ getting into the salvage business and snatching the bread out of professional salvagers’ mouths with either Monitor or H.L. Hunley, in both cases, while government archaeologists were involved to do excavation in advance to make sure recovery did not adversely impact archaeological finds outside or around the two vessels, the recovery of Monitor’s engine, propeller, and turret was done in combination by U.S. Navy mobile diving and salvage unit (MDSU) divers in conjunction with Oceaneering, Inc. — a private firm. Oceaneering also recovered Hunley.”

For Delgado, a crucially important aspect of the SMCA is that it’s not a blanket prohibition on looking for, finding, and diving on naval wrecks, but it does prohibit taking things away from these sites.

“If there is a risk to the site, the Navy and/or their partners have acted to scientifically recover artifacts, restore them, and put them in a museum,” said Delgado.

Artifacts, history, and archaeology aside, many of these wrecks are very dangerous, containing environmental and public safety hazards like oil or unexploded bombs. In the case of the USS Independence — a sunken World War II-era aircraft located off the coast of California’s Farallon Islands — the wreck is actually radioactive.

It’s also important to remember that military wrecks are, in the words of the US Navy, “the final resting places of sailors who paid the ultimate sacrifice in service of the nation.” Some of these wrecks contain the bodies of people whose relatives still alive today, which is no small thing.

“That these are war graves is a very important consideration,” Frank Cantelas, Acting Director of the Maritime Heritage Program at the NOAA’s Office of Marine Sanctuaries, told Gizmodo. “There’s usually some tragedy involved, and we need to keep that in mind when we’re looking at these sites. We also need to preserve the story about how they got there, who was on board, and what they were doing, while also recognising that many of them have families and descendants who are still alive. I’ve personally had experiences where families of the dead have reached out to me to talk about the wreck site where they know a loved one has been lost, and they’re curious to know how it looks today.”

At the same time, Cantelas says shipwrecks are a glimpse of how people lived in the past – a time capsule that provides evidence of our ancestors. He said, “Preserving them means we’re helping to preserve our heritage for the future.”