Attempts to kill a mosquito aren’t always met with success — these annoying bloodsuckers seem preternaturally good at evading hand swats. Surprising new research suggests mosquitoes learn from these near-death experiences, staying clear of a particular odour they have learned to associate with the perpetrator.

Image: Kiley Riffell

New research published in Current Biology suggests mosquitoes are more adept at acquiring and processing information than we thought possible. In experiments, mosquitoes learned to associate an odour with a jarring vibration meant to simulate the feeling of getting swatted.

The insects learned from these episodes, actively avoiding the scent during subsequent exposures. Importantly, the University of Washington scientists who conducted this research say it’s possible to switch off this learning capacity, potentially offering a new approach to mosquito control.

If Satan himself were asked to design a creature to torment humanity, he would have most certainly come up with the mosquito. These flying insects are associated with more human deaths per year than any other animal on Earth. To find their hosts, female mosquitoes use a highly sensitive “nose” consisting of antennae, a proboscis, and a pair of mouth appendages called palps.

Some species even have a second “nose” specifically designed to sniff out humans. Some studies suggest mosquitoes are especially attracted to human hosts infected with malaria. Their highly specialised odour sensors can discern between thousands of different aromatic compounds, allowing them to hone in on a desired target.

And indeed, mosquitos don’t choose their victims at random. As many of us can attest, these bugs are picky eaters, exerting a preference for who or what they bite. Their preferences also change depending on the time of year, choosing to torment birds in the summer and mammals during other parts of the year.

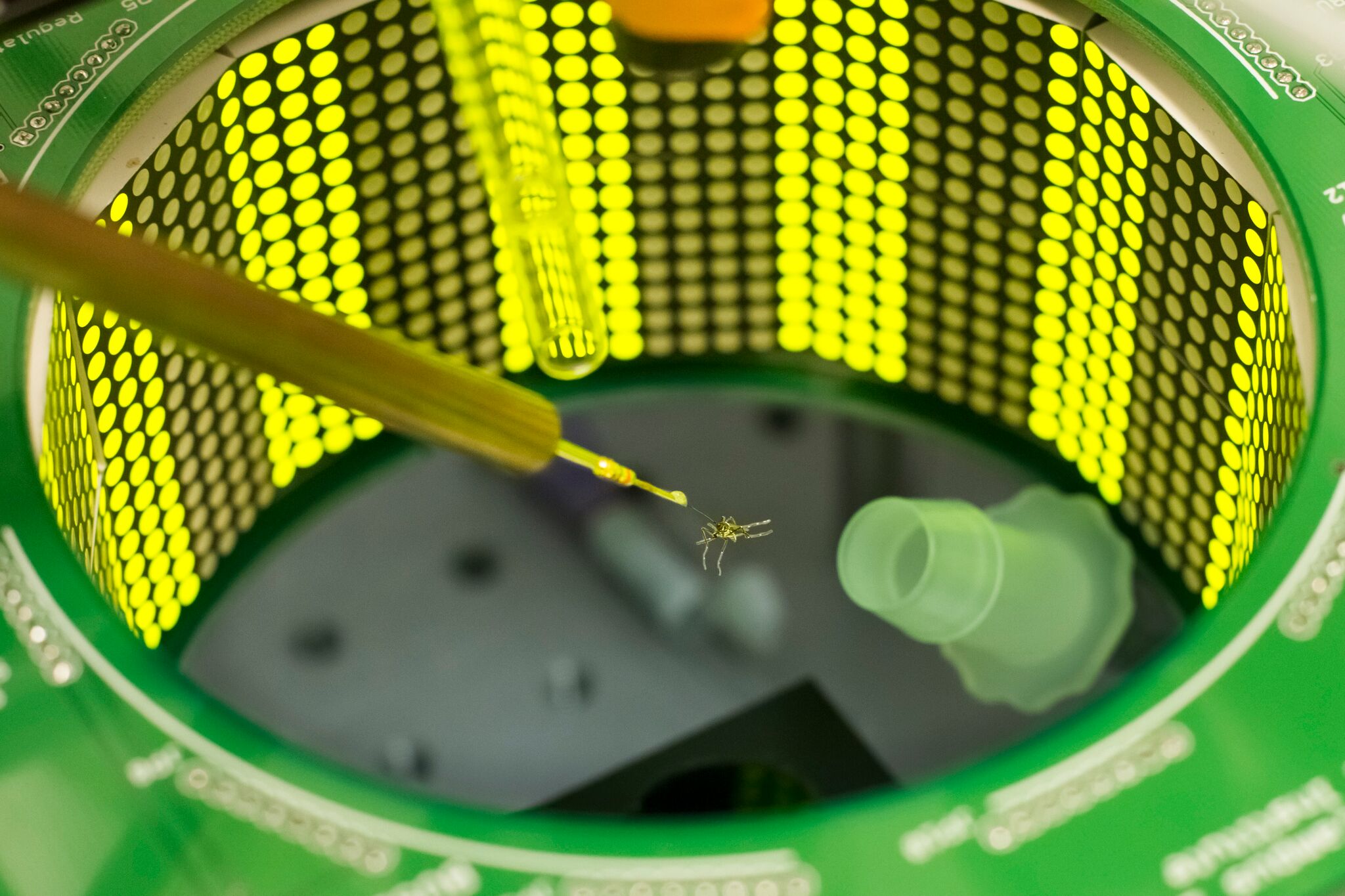

That mosquitoes have a tremendous sense of smell and are discerning is well established, but a UW team led by Jeffrey Riffell wondered if their preferences might also be learned. To find out, they performed an experiment with mosquitoes, rats, and chickens. Using a machine called a “vortexer”, the researchers were able to expose mosquitoes to a mechanical shock that simulates the feeling of being near a hand that’s making a swat through the air.

Mosquitoes were trained to associate this simulated swat with the smell of rats and chickens. In subsequent tests, mosquitoes steered clear of the rats, but for some reason weren’t able to resist the chickens (more on this in just a bit).

A mosquito in the “vortexer” machine, which simulates swats. (Image: Kiley Riffell)

As the new research shows, the effect wasn’t subtle. “Once mosquitoes learned odours in an aversive manner, those odours caused aversive responses on the same order as responses to DEET, which is one of the most effective mosquito repellents,” said Riffell in a statement. “Moreover, mosquitoes remember the trained odours for days.”

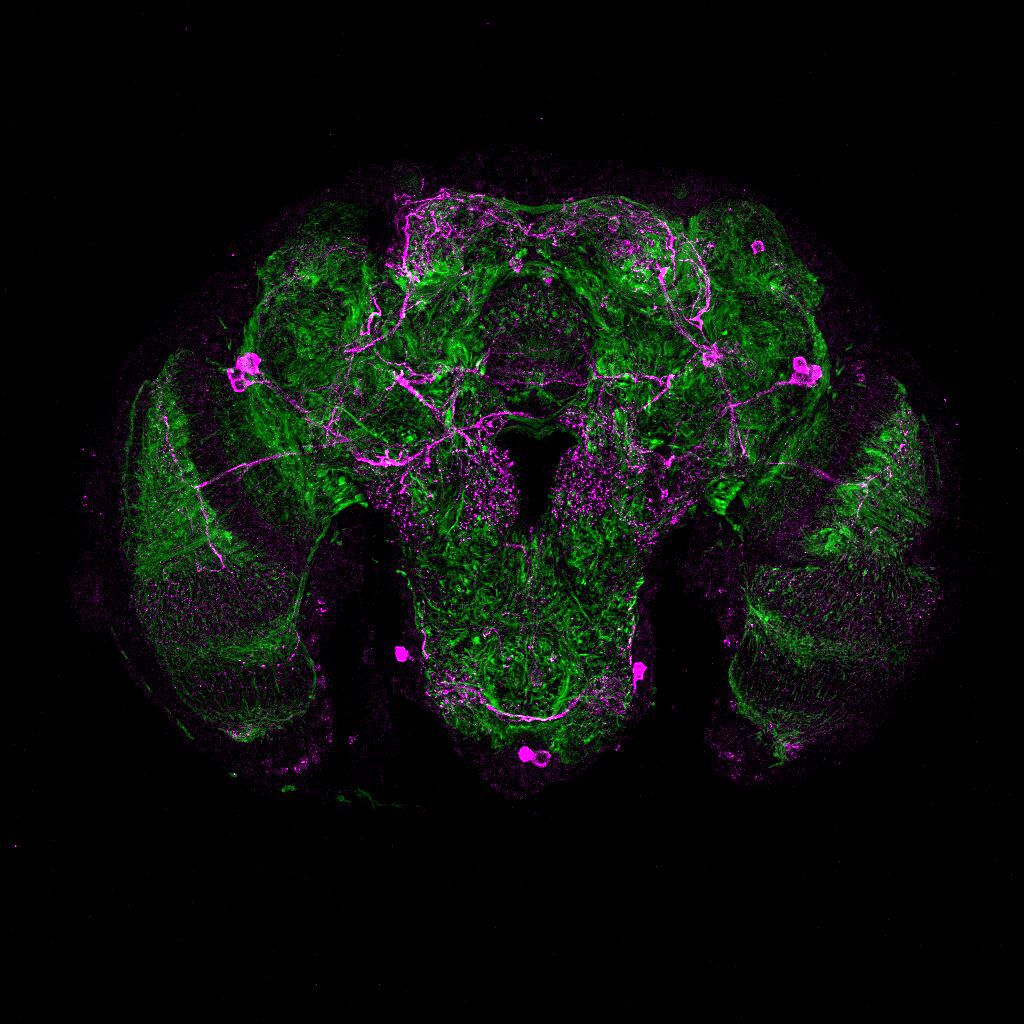

These bugs have teeny, tiny brains, so it’s reasonable to wonder how mosquitoes are even capable of processing such complex information and then acting on these experiences. The answer, say the researchers, comes in the form of dopamine — an important neurotransmitter involved in learning. Dopamine is a vital cue for learning and memory in both insects and mammals, especially in terms of remembering what was happening in the presence of bad or good stimuli.

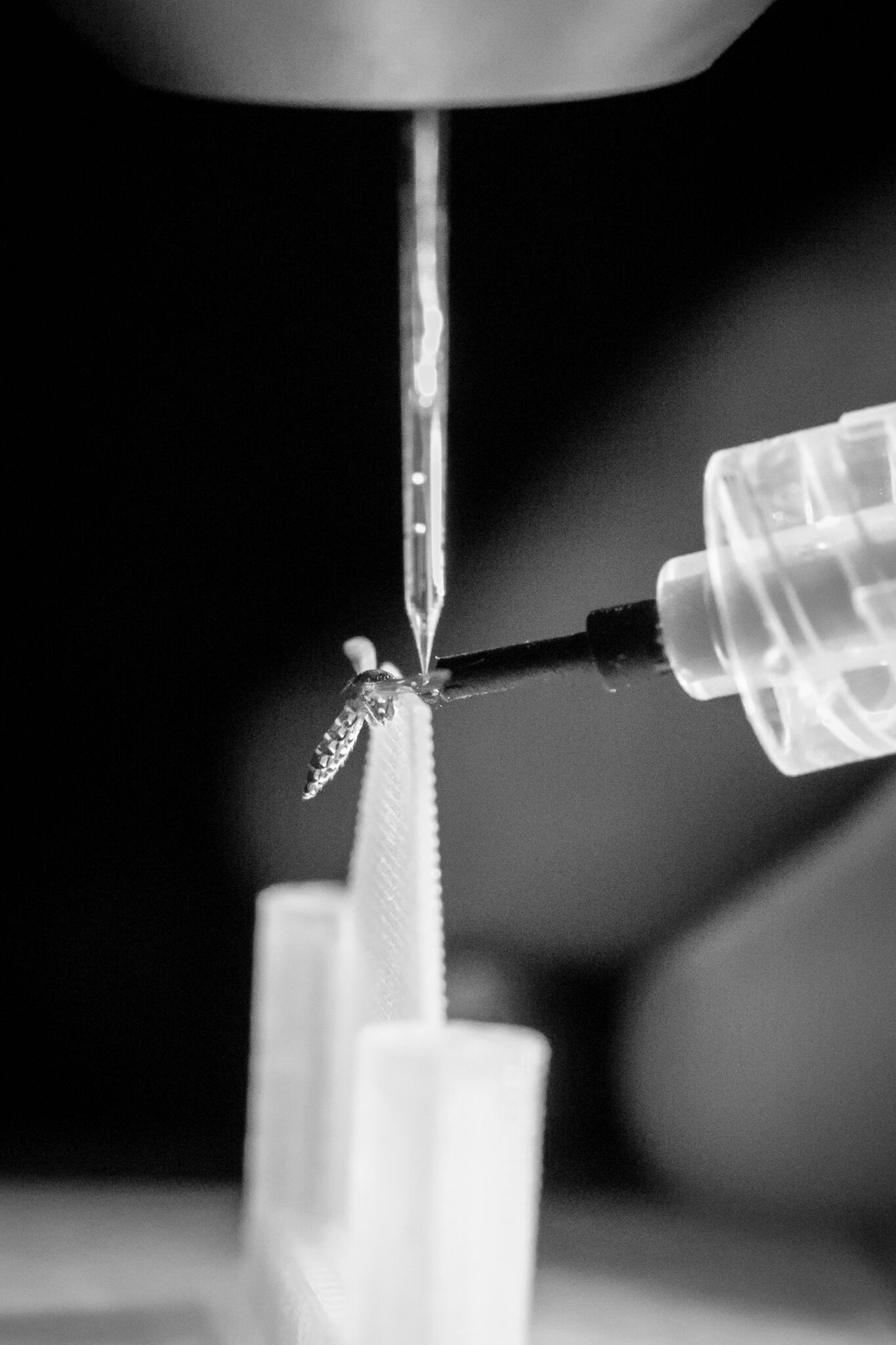

To prove that dopamine is behind this insectoid trick, Riffell’s team produced genetically modified mosquitoes that lacked dopamine receptors. In experiments, these mutated mosquitoes were glued (yes, glued) to a 3D-printed rack. Unable to get away, the researchers exposed the mosquitoes to various scents while recording their brain activity. Specifically, the researchers were measuring the activity of neurons in the olfactory sensors of their brain.

Unable to process dopamine, the neurons were less likely to fire, suggesting that mosquitoes without dopamine receptors are less capable of processing and learning from odours.

Sorry not sorry. A mosquito glued to a 3D-printed rack. (Image: Kiley Riffell)

This has obvious implications for mosquito control.

“By understanding how mosquitoes are making decisions on whom to bite, and how learning influences those behaviours, we can better understand the genes and neuronal bases of the behaviours,” said Riffell. “This could lead to more effective tools for mosquito control.”

Floris van Breugel, a research associate at UW’s department of biology, isn’t entirely surprised by the finding.

“Many insects have been shown to learn and associate odours with appetitive and aversive stimuli, and the idea that this occurs through a dopaminergic pathway is consistent with prior literature,” she told Gizmodo. Van Breugel wasn’t involved in the new study, but she has worked with Riffell and study co-author Michael Dickinson in the past.

“Yes, insects are extremely good at associating odours with whatever else might be going on when they smell something with that odour”, Christopher Potter, a researcher at Johns Hopkins Medicine who wasn’t involved in the study, told Gizmodo. “For example, in classical learning and memory experiments in fruit flies, researchers puffed an odour along with electrical shocks to the insect’s feet, and the fly learned very quickly to avoid that particular odour.

It is very plausible that different unpleasant aspects of the swat, such as the rushing feeling of the wind, the banging of the hand close to the mosquito, could then be remembered along with the smell of the person.”

Pink stains show dopamine in the mosquito’s brain. (Image:

Potter says the new study is important because it shows that interactions between mosquitoes and people are a lot more complex and interesting than previously thought.

“It suggests that mosquitoes are paying very close attention to what we do to them, and that not only a life-or-death near-hit can be remembered, but that the human smells — and likely the person — associated with the near-hit can be avoided in the future,” he said.

As for the mosquito’s inability to avoid chickens, van Breugel says it’s also not surprising.

“Different mosquito species have different host preferences — some prefer mammals, some prefer birds, and some even prefer amphibians like frogs,” she said. “By testing both rats and chicks, the authors showed that these mosquitoes preferentially learned odours associated with mammals, but not other organisms.”

In light of the new findings, van Breugel imagines traps that emit human-like odours, and when a mosquito visits them, a simulated swat (i.e. an aversive stimulus) could be administered to the insects. By training them this way, she says the mosquitoes might spend less time hunting humans — and without the need for completely eliminating the species. “Whether or not it would work, is an open question,” she said. “Indeed, mosquitoes rely on my cues to find their hosts, but odours are a particularly strong one.”

As to whether or not the researchers have proven that swats will make mosquitoes go away, that’s still an open question. The experiments involved rats and chickens, and not humans. What’s more, the work was done in the lab, and not in the real world. To know if swatting truly has an effect on these insects, van Breugel says we’d have to know how effective the average human is at swatting; if mosquitoes are killed with 100 per cent accuracy, for example, there would be no opportunity for learning.

“One thing is clear, however, the outcome for you is better if you do swat, regardless of whether you land the hit or not,” said van Breugel.