It’s a microscopic case of mistaken identity. A new study published in PLOS Pathogens has found that a 16th-century mummified child may have actually been infected by an ancient strain of hepatitis B, not smallpox as scientists believed for decades. But the finding, if correct, adds even more mystery as to how this still widespread, often fatal virus has evolved and plagued humanity over centuries.

Image: Gino Fornaciari/University of Pisa

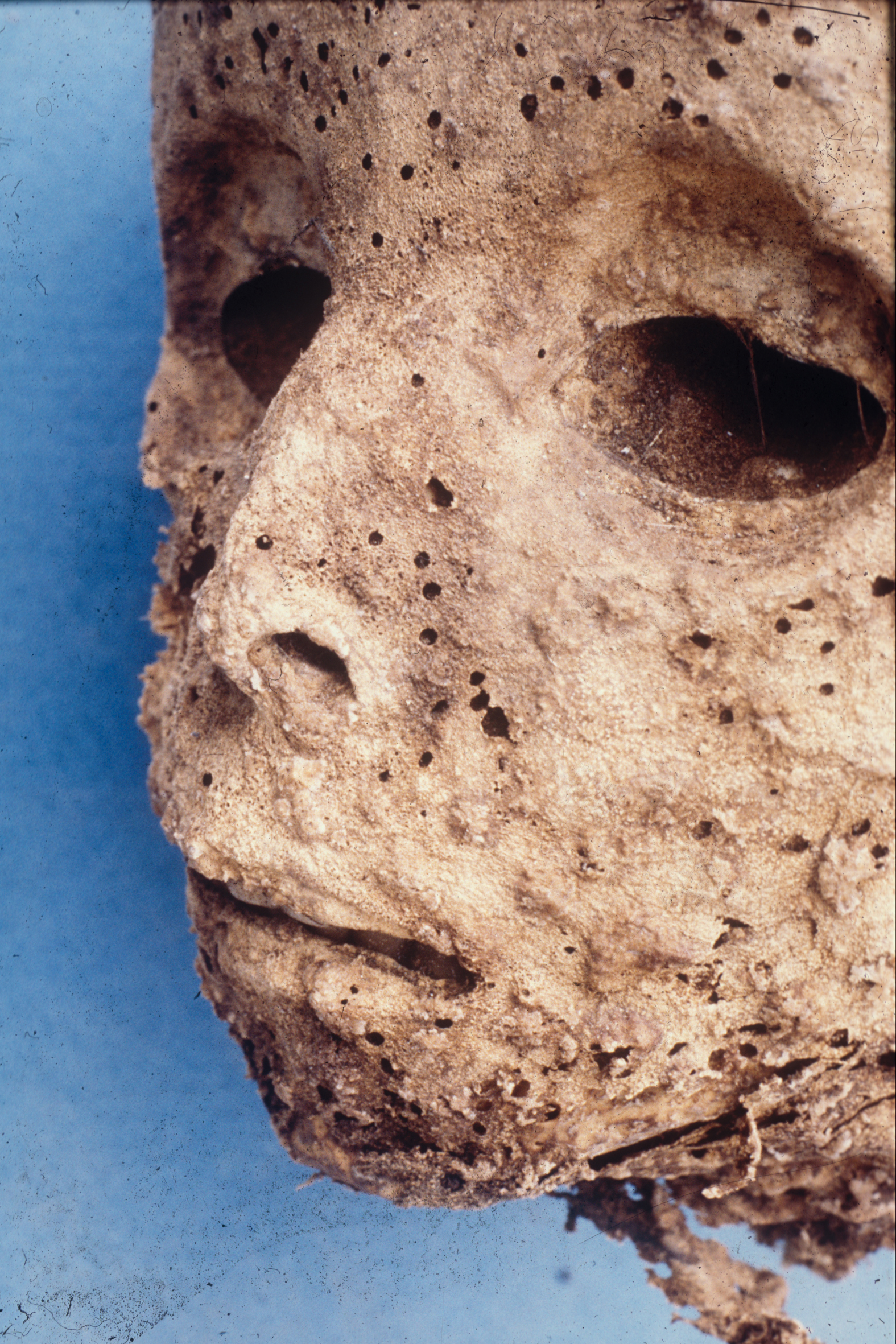

The mummy in question was buried sometime around 1569 in the Basilica of Saint Domenico Maggiore, a 13th-century church in Naples, Italy. Soon after it was exhumed and autopsied in the mid-1980s, scientists concluded the child had smallpox, a now-(mostly)extinct virus that ravaged mankind since at least the heyday of Ancient Egypt.

They settled on smallpox because the child had a clear rash across their arm, body, and face, and also because a tissue sample (taken from one of the rashy bumps) seemed to show egg-shaped particles that resembled pox underneath an electron microscope.

The researchers of this current study, however, performed the same sort of test under the microscope and couldn’t find any viral particles, smallpox or no. But when they analysed the DNA of small bone and skin samples from the child’s femur, rib and other body parts, they did find bits of DNA belonging to hepatitis B, suggesting the child had long been infected with the virus at the time of his or her death.

Because of that, the researchers speculate, the child’s rash, long a hallmark of smallpox, may instead have been a rare childhood condition called Gianotti Crosti syndrome, which is known to be caused by lots of viruses, including hepatitis B.

Image:Gino Fornaciari/University of Pisa

“These data emphasise the importance of molecular approaches to help identify the presence of key pathogens in the past, enabling us to better constrain the time they may have infected humans,” senior author Hendrik Poinar, an evolutionary geneticist with the Ancient DNA Center at McMaster University in Canada, said in a statement.

Once the team sequenced the entire genome of the ancient virus, though, things got even weirder. The strain they found in the mummy looked practically indistinguishable from a modern day strain of hepatitis B belonging to the same genotype, with no signs of evolutionary change.

That, especially in the microscopic world, is bizarre. Microorganisms tend to evolve (read: mutate) at an alarming rate compared to every living thing else in the world, and viruses even more so. That’s why bacteria are staging a frightening comeback against antibiotics and why we need to vaccinate against the flu every single year.

So this could mean one of two things. EIther the researchers screwed up and contaminated their sample somehow (unlikely, they say, due to other evidence supporting the virus’ ancient origins). Or hepatitis B is a stodgy exception among viruses. The virus certainly evolved and split off from its ancient relatives at some point in history, but this study suggests the virus may have found and stuck to its niche in the circle of life since at least the 16th century.

The virus might evolve plenty in the short term, the researchers speculate, but these mutations largely don’t get passed onto future generations, making it seem as though the virus overall hasn’t changed much. That also likely means it will be that much harder to ever figure out when and how we first crossed paths with hepatitis B, at least with current technology.

“The more we understand about the behaviour of past pandemics and outbreaks, the greater our understanding of how modern pathogens might work and spread, and this information will ultimately help in their control,” Poinar said.

That’s important because hepatitis B, unlike smallpox, still remains one of humankind’s worst thorns, despite the availability of a vaccine against it since the 1980s. At least 250 million people are chronically infected with the virus, including up to 2 million in the US and it’s estimated to help cause around a million deaths annually, often through chronic liver damage.