Everybody knows that computers were huge and unwieldy in the middle of the 20th century. But a lot of the tech terminology that we take for granted today had to be invented at some point. Such is the case with the term “desktop computer”, which emerged long before “personal computers” became commonplace in homes.

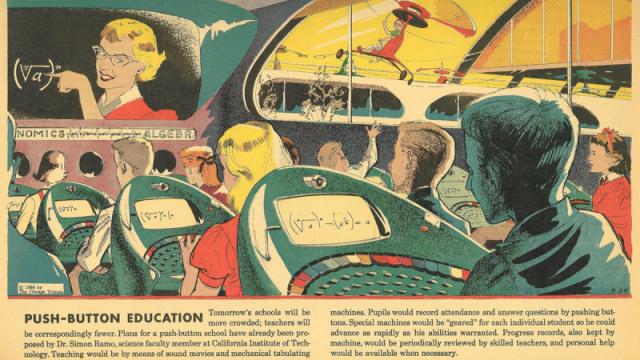

The 5 May 1958 edition of Arthur Radebaugh‘s Sunday comic, Closer Than We Think, which featured the school of tomorrow

You probably never think about it here in the 21st century, but the term desktop computer, which is recorded as early as 1958, entered the wider technical lexicon in the mid-’60s as computers transitioned from devices that would fill up an entire room to those that could fit on a desk.

The November 1966 issue of Computers and Automation magazine had a great article that not only explored these futuristic “desk top” computers, but also looked at the other advances that were revolutionising computer technology at the time.

The section in the article on super-storage and super-retrieval will be particularly interesting for those of us who only think of storage in 21st century terms. When storage consisted of tape, it wasn’t too difficult to store information. But what about when it came time to find what you were looking for? It wasn’t so easy with tapes.

We’re spoiled by storage devices such as USB drives that you plug in and just drag and click. But then again, every generation is a bit more spoiled technologically than the one that came before it.

Some excerpts from the November 1966 issue of Computers and Automation:

Once upon a time, not too long ago, the status of computer companies was determined by how many square feet of space their equipment occupied and how many tons of air conditioning it needed. The “almost block long” computers were undisputed kings. A little later, computers with the highest transistor count were considered the ultimate in sophistication.

This is no longer true. As the art and the applications progress, such “sophistication” becomes increasingly unnecessary.

Now it is considered fashionable to call one’s computer “desk top” – although often a very special “desk” has to slip underneath or by its side to support it physically and electronically.

And there’s the truly amusing part. Even as the computer was evolving into something that could fit on a desk, there were still plenty of adjustments that needed to be made for it to fit.

Desk-Top Computers

A great many desk-top computers have made their appearance during 1965-66. A prime advertising point has been that they are fast and noiseless compared with their mechanical predecessors. In some models this is the only advantage.

Many manufacturers, however, have provided some additional, significant advantages:

1. The ability to store many numbers.

(It is difficult to store more than a few numbers in a mechanical desk top computer.)

2. The ability to accept machine inputs and produce machine outputs; that is, outputs that can be used again as inputs either in part or in total.

Punched tapes, punched cards, or special inserts are the most commonly used machine input/output media. Even though relatively slow, they are flexible, compatible, and economical; they expand greatly the memory and programming capacity of the small computer and provide a vital key for the future increase of small computers.

Automatic input and output are very important even for small computers, because the time for manual keying for input and manual reading and transferring of output largely over- shadows the time for computing. Also this kind of manual work is very unsuitable for the human brain, which here is famous for the quantity of its errors.

If you talk to someone who worked in computing in the 1970s they will tell you about bringing enormous stacks of punch cards to feed into a computer. These days it’s hard to imagine that doing such a thing was considered the easy and “automatic” alternative.

Time-Sharing, 1966

This was a year when more was heard about time-sharing than about any other single computer subject. But great joy and acceptance has yet to come from the users rather than from advertising departments.

In some cases a central data processor is decidedly the right solution because of the centralised nature of the problem. However, in most cases the logistics of using a remote computer, together with the extra cost and complexity of programming and data communications, make the universal acceptance of time-sharing less than a foregone conclusion.

Where local computational ability is required, the small computer will be the answer because it has no problem of data communications. Also it is devoid of the logistics problems of having to share a central facility.

As I mentioned earlier, the idea of being able to store information fairly easily but having difficulty retrieving it is a fascinating one in the history of computers. The article addresses this issue and perhaps causes us to reflect on the ways in which we still struggle with information retrieval here in the 21st century. Sometimes those struggles aren’t strictly from a technical standpoint, given the relative ease with which we can quickly copy a file from a drive. The difficulty here in 2017 more often comes with finding the information you’re looking for among documents that may not be machine readable yet, such as a scanned document with type that hasn’t been put through OCR software.

Super-Storage and Super-Retrieval

Most of the advances in information handling in the past decade have been in the application, cost, and reliability of information transformation. The ability to store has changed relatively little.

Super-storage has always been available, but not super-retrieval. Huge amounts of information can be stored on tape or, for that matter, in printed form; but accessibility has so far been somewhat inversely proportional to storage capacity.

In spite of many efforts for improvement, information retrieval remains a great technical and conceptual roadblock in information technology. The solution to the popularly- called “information explosion” is severely hampered by lack of retrieval technology and by a basic lack of definition and understanding of what information is and what it is not.

When computers started to become mainstream in business circles as large hulking machines, there were instances when companies bought the things but had no real use for them. Maybe that’s just the nature capitalism, but it was a very real issue worth addressing when not everyone was sold on this whole computer revolution.

The article from 1966 explains this difficult situation, noting that people might brag about having a computer as it sat in the corner doing nothing:

Large Computer, Small Computer, No Computer?

Voices of disenchantment have been raised in the last few months. For the first time, it has become fashionable to throw the computer out and replace it again with a “personal touch.” “Our attempts to utilise electronic data processing in billing our accounts have been unsuccessful, it has caused us to become too mechanical in our handling of our subscribers,” writes an answering service to its subscribers. This is in sharp contrast to previous habits of bragging about the computer standing in the corner, even though it had barely been un-packed.

Many of these problems have been caused by overselling large general purpose computers to customers who had only limited, special problems; and the customers then got entangled in endless programming efforts rather than in solving their problems.

To be sure, for very dissatisfied customer of electronic data processing there are ten satisfied ones. There are ‘even some who could no longer operate without electronic data processing. Nevertheless, it is in the interest of everyone concerned with the industry to avoid dissatisfied customers, and to consider “when not to use a computer.”

Another thing we take for granted here in the 21st century is the modern keyboard. But that was yet another thing that had to be invented and then become adopted by the wider computer community.

The Computerised Typewriter

The day of the “computerised typewriter” is coming. In the past, typewriter-like devices have been used for various odds and ends on the periphery of computer systems. The next few years will see a reverse trend. Typewriter-like devices, which have computing, memorising, selecting and processing capabilities will make the, computerised typewriter compete in popularity with the present electric typewriter.

Technically, there may be nothing new. Practically, the computerised typewriter may mean a change as huge as the success of desk-top copying machines – even though the technical capacity to make copies had existed for many decades.

Again, it’s fascinating to read about the emergence of the “computerised typewriter” in 1966, a time when plenty of people saw things such as the light pen as a useful input device that was more than likely going to take over the future.

We take so much for granted when it comes to technology today. Even a term like the “internet” is so ingrained in us that we can forget it had to be coined, competing with other potential monikers such as “the catenet”. But no technology is simply born. People have to build it and name it and develop it. And as was the case with the desktop computer, people had to decide that they wanted to keep calling it that.