Facebook is a vast and bewildering operation, working with visible and invisible data streams via opaque algorithms on a scale larger than humans can readily comprehend. Many of us have been baffled, for example, by the social network’s ability to figure out who we know in real life, as reflected by the suggestions that pop up in its “People You May Know” box.

Illustration by Sam Woolley/GMG

That confusion, it’s now clear, extends to Facebook’s own communications department. Judging by my experiences reporting on the feature, even Facebook is confused about exactly how it works.

Last week, I wrote about how Facebook’s use of intrusive data-mining to connect its users can out sex workers and porn stars to their clients, families, and friends. While reporting the story, I asked Facebook if there was a way to opt out of the feature, for people who don’t want alternative identities exposed to people who shouldn’t know them.

The Facebook communications staff had almost two weeks to look into this. This week, a spokesperson got back to me and wrote that “an opt out is not something we think people would find useful.” But she said there was a workaround.

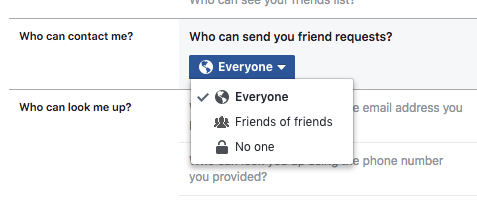

“People can always control who can send them friend requests by visiting their account settings,” the spokesperson wrote in an email. “If they select ‘no one,’ they won’t appear in others’ People You May Know.”

It wasn’t a perfect solution, but it made sense: If you made it impossible for anyone to send you a friend request, Facebook would stop encouraging people to friend you. I went to the setting on my own account and took a screenshot that I included in the article.

But there was a problem. After the story was published, several people told me that they had tried to take advantage of this setting, only to find out that they didn’t have the “no one” option. They could only allow “Everybody” or “Friends of Friends” to send them friend requests.

I’ll send a few, I’m on a

Samsung tablet, def. No option none. pic.twitter.com/DRVTV6Mjd2— carl (@carl_fx_) October 11, 2017

When I reached out to Facebook about this, asking why some users didn’t have the “no one” option, a spokesperson confirmed that the original advice wouldn’t work. Not every Facebook user has the “no one” option, and even for people who do, it doesn’t provide a workaround.

“In my note, I said if people restrict who can send them friend requests to ‘no one’, they won’t appear in People You May Know suggestions,” she wrote. “I made a mistake and gave you inaccurate information. People may still appear as suggestions.”

If people whose full-time job it is to understand Facebook’s myriad account settings don’t understand them, how is a normal user supposed to? As for the question of why some people have the antisocial “no one” option and others don’t, the spokesperson cc’ed Matt Steinfeld, Facebook’s head of policy communications, to explain.

“We told you that there is a way to turn off the ability for people to send you friend requests by selecting ‘no one,’” Steinfeld wrote. “We were wrong. That option doesn’t exist unless you’re someone with a lot of followers, like a public figure. However, everyone can change the setting to ‘friend of friends.’”

(As a tech writer, I’ve picked up 100,000 followers on Facebook, which is why I had access to the “no one” option)

Even if you tell Facebook that “no one” or only “Friends of Friends” should be able to friend you, though, it will still offer your account in “People You May Know” to anyone Facebook thinks might know you — including people who won’t be able to send you a friend request.

I said that seemed like an odd design choice. Steinfeld agreed, and said it is going to change.

“You mentioned that it’s odd that someone could be suggested in People You May Know, even if they have adjusted their settings to only receive friend requests from ‘friends of friends,’” he replied. “It’s a fair point, and we’re fixing this.”

So as a result of this story and follow-up, Facebook will eventually start doing a version of the thing they originally told me they were already doing.

Steinfeld also apologised for my having gotten the bad info in the first place. “We gave you incorrect information about People You May Know, which is an admittedly bad thing to do to someone who is trying to actually understand how it works — and who has said repeatedly that we’re bad at explaining it,” Steinfeld wrote.

This was not the first time Facebook has given me reportorial whiplash by telling me People You May Know works one way, then changing its mind after a story was published. Last year, I asked Facebook whether it was using location information from users’ smartphones to figure out who knew each other in the real world. Facebook told me it was, with a spokesperson telling me “location is only one of the factors we use to suggest people you may know.”

Shortly after I published that story, Facebook changed its tune and said that actually it wasn’t using location.

“We are not using location data to suggest people you might know. This includes IP and Wi-Fi access point location information,” a different spokesperson wrote in an email. He said that they had used location one time in a test, causing confusion internally. According to one source there, the people who run People You May Know are constantly running different experiments to improve the product, so how it works exactly is actually constantly changing and can vary from user to user.

Earlier this month, Facebook’s chief of security, Alex Stamos, wrote a string of tweets criticising press coverage of the tech industry and complaining about a “gap” between Silicon Valley and the reporters and academics who write about it. “My suggestion for journalists is to try to talk to people who have actually had to solve these problems and live with the consequences,” Stamos wrote.

Unfortunately, despite those wishes, Facebook has never let me speak directly with the engineering team responsible for People You May Know. Any questions I have about their problem-solving work are filtered through Facebook spokespeople. As a result, Facebook is unable to explain basic information about its own product.

This reflects a larger problem caused by Facebook’s immense growth and increasing complexity; as Alexis Madrigal recently wrote in The Atlantic with regards to the role of fake news and targeted ads on Facebook in the most recent election, “no one knew everything that was going on on Facebook, not even Facebook.”

And that is a bit terrifying. This big blue machine plays an ever-expanding role in society and in the lives of many individual users, but no one seems to have a solid grasp on either the minutiae of what’s going on there or the larger repercussions of it.

“Having read your story, I also want to say we’re not thrilled when we see someone like Leila [ed note: the sex worker] having a bad experience on Facebook,” Steinfeld wrote. “We want to do our best to prevent these things from happening and we do care about people’s privacy. We fell short here, and we will do better.”

In the case of People You May Know, the most simple solution would be for Facebook to give its users access to their own data, and control over it. Along with offering to connect one person to another, it could explain what data it used to suggest that connection, and offer a clear way to opt out of it.