It’s a well-worn fact that our round Earth is warming, and that human carbon emissions are the cause. What’s less well-known is how much warming we’ve already committed our planet to in the future. A new study crunched some numbers and came to an alarming answer — but other experts are already criticising its approach, reminding us that the course of climate change remains incredibly tough to predict.

Image: Lima Andruška/Flickr Creative Commons

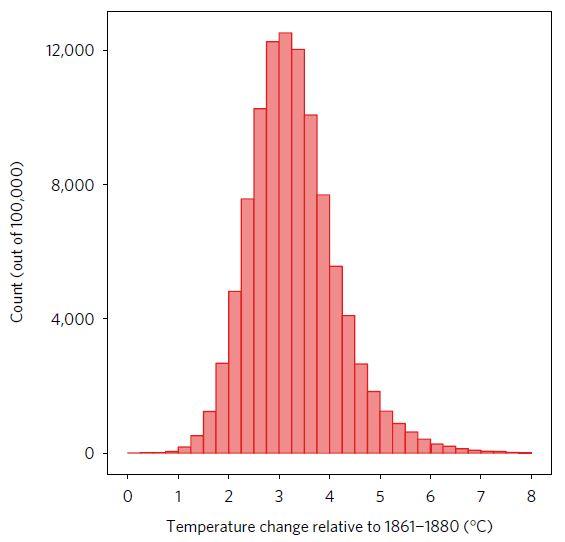

The 2C warming target — adopted by scientists and politicians alike as a threshold we ought to stay below to avoid catastrophic climate impacts — is very likely to be surpassed this century, according to a study out in Nature Climate Change today. Using statistical models that project trends in socio-economic factors such as GDP and population growth forward in time, the University of Washington-led study estimates there is only a five per cent change Earth will warm less than 2C this century.

Depressingly, the authors estimate just a one per cent chance that we’ll remain below 1.5C of warming, the “stretch goal” set forth in the Paris Climate Agreement, which is thought to offer low-lying island nations the best chance of remaining above water. Instead, the authors estimate a 90 per cent chance temperatures will rise 2C to 4.9C by century’s end.

On the one hand, this isn’t surprising — many experts believe we aren’t reducing our collective carbon footprint quickly enough to align with the Paris goal. The planet has already warmed about 1C since pre-industrial times, and we know that there’s more warming baked in as economies make the transition to renewable energy, and as heat taken up by the oceans is re-released to the atmosphere. Another study out in Nature Climate Change last week also suggested we’re more likely to breach the 2C threshold than previously thought, because of uncertainty in how we define our pre-industrial “baseline” level of CO2.

Projected global average temperature change by 2100 according to the new study. Image: Adrian Raftery/University of Washington

But when I sent the new paper to climate scientist Michael Mann, one of the co-authors of last week’s study on defining the pre-industrial baseline, he was immediately critical of its methods. “Colour me deeply, deeply sceptical,” he said, noting that while his study described physical constraints on warming (that is, how much CO2 we’ve already emitted), the new study is based purely on socio-economic trends — and assuming that those trends can foretell the future.

“That ignores the fact that political will depends on many factors that cannot be predicted based on past behaviour,” he said, noting that the recent growth in renewable energy, for instance, has exceeded the projections of many market forecasters.

Ken Caldeira, a climate scientist at the Carnegie Institute for Science, noted that while the conclusion of the paper was wholly unsurprising, projecting the trajectory of complex social systems amounts to little more than stating one’s opinion. “In science, the leap from model to reality is always a dangerous leap,” he told Gizmodo. “Few predicted the fall of the Soviet Union, the unprecedented rapidity of the rise of China, or the election of Donald Trump.”

The question, as Caldeira put it, is how likely are humans to change their historical patterns of energy consumption — and when. “If we don’t change those patterns, then the world is likely to get very hot,” he said. “However, we will change those patterns. The question is whether we will change those patterns before we radically damage our environment effectively forever.”

I’ve reached out to Adrian Raftery, lead author of the new study, with some of the criticisms enumerated above. I’ve also reached out to a few other climate scientists to see what they think.

In an email to Gizmodo, study co-author Richard Startz responded to some of the above criticisms, saying that one of the goals of his team’s modelling approach was its ability to account for uncertainty. “Uncertainty about economic growth over the next 100 years accounts for half the total uncertainty in the model,” he said. “The bad news is that the band of likely outcomes range from pretty bad to outright disaster.”

To the point about the capricious nature of our political will to act, Startz emphasised that his team forecasts the world’s carbon intensity (a metric of carbon emissions relative to economic growth) “will fall as quickly as it has been falling for some time now. It would take a noticeable acceleration or deceleration to make a difference,” he said. “Perhaps some country will pull out of the Paris accords and cut progress. Or one could imagine a country investing in basic science in a way that brings forth technological breakthroughs at a far more rapid pace than has already been the case.”

But, in short, there’s still a lot of uncertainty about how much the planet will warm this century. Another study, also published today in Nature Climate Change, suggests we’re likely only committed to 1.5C of warming. The two new estimates are barely within the error bars of each other.

Of course, none of this changes the fact that we need to act quickly to avoid the worst consequences of climate change. So, what’s the average person to do about it all? If you live in a wealthy nation, here’s a list of choices you can make to align your lifestyle with the Paris goal. If enough of us make enough of these choices, it will help drive our economy in the right direction. But ultimately, the decisions that will lead to the most impactful shifts — those that cannot be predicted by models based on historical trends — are bigger than us. They’re policy decisions made at high levels of government.

So, you can also vote.