American scientists have accomplished a major first: For the first time on US soil, a human embryo has been genetically modified. The details of the breakthrough, which was leaked to the press last week, are reported in a study published today in the journal Nature.

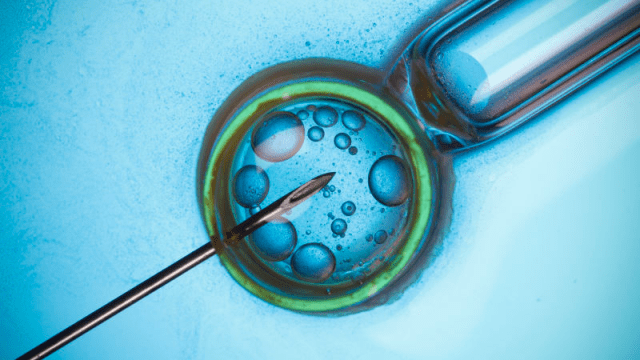

Image: Shutterstock

[referenced url=”https://gizmodo.com.au/2017/07/scientists-in-the-us-reportedly-just-edited-a-human-embryo-for-the-first-time/” thumb=”https://i.kinja-img.com/gawker-media/image/upload/t_ku-large/zhfq9xq3dekhfqsptyfg.png” title=”Scientists In The US Reportedly Just Edited A Human Embryo For The First Time” excerpt=”Human embryonic stem cells. Image. Wikimedia China has long been ahead of the US when it comes to human genetic engineering — there, the idea seems far less morally fraught. But for the first time, scientists in the United States have now genetically modified a human embryo, according to a new report in the MIT Technology Review. At Oregon Health and Science University, the publication reports, scientists are using the gene-editing technique CRISPR to alter the DNA of a “large number of one-cell embryos.”]

In their new paper, a consortium of scientists in California, Oregon and Asia detailed using the genome-editing technique CRISPR to repair DNA that causes a common genetic heart disease known as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. This is only the fourth published study involving editing human embryos; the other three all took place in China.

Aside from helping the US catch up to China in the genetic arms race, the study breaks some important new ground. Scientists at the Salk Institute in La Jolla, the Oregon Health and Science University and the Institute for Basic Science in Korea seem to have found a way around what’s known as “mosaicism”, a major problem thus far in embryo engineering in which some but not all of an embryo’s cells incorporate the engineered DNA. The research team cleverly side-stepped mosaicism by using CRISPR at the same time as fertilising the egg, before its cells had begun dividing. They effectively corrected the problematic sperm gene 72 per cent of the time, and even in those instances where they did not correct it, the problematic gene was still deleted.

The team also uncovered a new and potentially important DNA repair mechanism that takes place in early embryo development. The researchers used well over a hundred healthy donor eggs, fertilised with sperm from a donor with the gene for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. But rather than inserting new, lab-designed genes into the the embryo, the researches simply used CRISPR to cut the paternal gene in the right spot, and let the maternal version repair it with its own disease-free genetic code.

“This is not only a different technique for embryo editing, but the most encouraging fixing of an embryo with CRISPR to date,” Eric Topol, a geneticist at Scripps Research Institute who was not affiliated with the study, told Gizmodo. “That doesn’t mean that this [embryo] is ready for implantation in the womb, but it does demonstrate a technology that is better suited for eventual success.”

The study was not, however, the world-altering breakthrough it was made out to be after news of the forthcoming paper was leaked to the MIT Technology Review last week, and covered by most major media outlets, including Gizmodo.

“It’s an incremental step that moves us a little closer [to editing human embryos], but this [technology] isn’t right around the corner,” Stanford bioethicist Hank Greely told Gizmodo.

Greely pointed out that the applications for this technology are actually pretty narrow. There are two major scenarios in which editing the DNA of an embryo might be considered ethical: One in which both parents carry a gene for a genetic disorder recessively, and one in which one parent carries a dominant gene for a disease, like hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or Huntington’s disease. This technique would only work in the second case.

“Looking at it more closely, it’s less useful than you might expect, if it works at all,” Greely said.

The new technique, it’s worth noting, is also unlikely to bring about a much-feared future of designer babies, since rather than inserting new DNA into embryos, it relies on the healthy DNA of one parent to repair the DNA of the other. In one embryo, the researchers did attempt to insert new DNA, but that embryo experience mosaicism.

“CRISPR is just targeting and doing the cutting. We’re not inserting anything,” Jun Wu, a lead author on the paper from the Salk Institute, told Gizmodo. “We’re only here to repair mutations. It’s not useful for things like designer babies.”

In February, the National Academy of Sciences released a 261-page report that gave a cautious go-ahead to human gene-editing, endorsing the practice for purposes of curing disease and for basic research but determining that uses such as creating designer babies are unethical. Wu stressed that the new study is squarely in the “basic research” category.

In the US, Congress has blocked any clinical trials with the aim of turning an edited IVF embryo into a baby. It has also made it hard to do research on human embryos at all, blocking federal funding for any clinical research “in which a human embryo is intentionally created or modified to include a heritable genetic modification”. In the new study, researchers discarded the embryos a few days after fertilisation. There is still no indication as to how they might fare if actually implanted in a human womb.

“We need to see if this can be replicated and evaluate the safety,” said Wu. “One of the major concerns is whether there will be off-target effects. We didn’t observe any in this case, but we need to evaluate it in other cases.”

Early days as it is, the new study brings up interesting ethical questions. Why, for example, embark upon genome editing when technologies like genetic screening combined with in vitro fertilisation could allow doctors to simply pick disease-free eggs to implant? How would you regulate this, and make sure that it’s equally accessible? What kinds of genes should we consider “ethical” to correct? There are an awful lot of unknowns.

In the mean time, though, scientists still have a lot to work out.

“We need more debate,” Wu said. “But for now, scientists just need to do more basic research.”