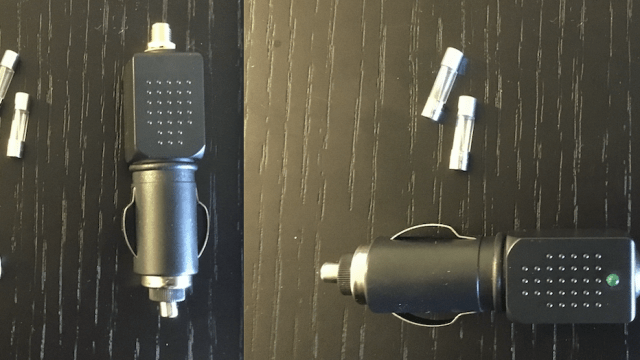

I ordered it on eBay. When the four-ounce envelope arrived from New York three days later, it looked innocuous enough. It contained a finger-sized black plastic box, a small black antenna to screw onto that box, and two glass fuses. It was designed to fit into a car’s 12-volt electrical socket — that thing that used to hold a cigarette lighter.

Image: Vlad Gostomelsky

The jammer, as it arrived (left). Assembled (right).

If I were to plug the gadget into my car, it would jam up the Global Positioning System signals within a 4.88m radius, rendering my smartphone’s Google Maps app useless and disabling any tracking devices that might be on my vehicle. That may sound harmless enough, but when one considers that thousands of lives (everyone in an aeroplane right now, for instance) and billions of dollars depend on reliable and accurate GPS signals, it’s easy to understand why my little jammer and others like it are illegal to use, sell, or manufacture in the United States. Every time I turn it on, I could incur a $US16,000 ($20,184) fine.

But they’re easy to get online, and I’m not the only one who has ordered one.

For the last eight months, security researcher Vlad Gostomelsky has been operating sophisticated detectors around the country to find out who’s using GPS jammers in the wild, and why. His research has turned up fascinating cases of everyday people using the jammers despite the risks — he’s seen truckers trying to avoid paying highway tolls, employees blocking their bosses from tracking their cars, high school kids using them to fly drones in a restricted area, and even, he believes, undercover police officers using them to avoid tails — and demonstrates that in the wireless world, devices that you use to avoid detection can actually make it easier to find you. You just need to be looking in the right channels.

The sale and use of jammers, even by police, is a federal crime with punishment ranging from fines to prison time. Whatever a user’s individual reasons may be, the jammers can present a serious threat, scrambling the satellite signals that vital systems — phones, aeroplanes, the New York Stock Exchange — depend on. When one of them is in use, those systems can go haywire.

The Global Positioning System relies on precise time data being sent from 31 satellites equipped with atomic clocks in space; a receiver calculates its location by determining its precise distance from a handful of those satellites. It’s not used just for navigational purposes but also for precision timing to, for example, document market trades (time is indeed money). GPS jammers work by broadcasting noise on the same frequencies used by the satellites, so that receivers can’t pick up the signals. Depending on the broadcasting strength of the jammer, it can knock out GPS reception for a few yards or for miles.

In June 2015, planes flying into Northeast Philadelphia Airport kept reporting that they were losing the GPS signal on the last mile of their approach. An agent from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), which enforces prohibitions against jammers, came to investigate and discovered a truck in a nearby parking lot. The driver said that he was using a jammer to disable a tracking device in his vehicle, and that he hadn’t realised the jammer was illegal. According to a governmental aviation safety report, the agent “confiscated the jamming unit and destroyed it with a sledge hammer.”

There’s no record of that particular incident on the FCC’s “jammer enforcement” page, which means the trucker may have gotten off easy. Other people have faced big fines for the use of the devices, such as Gary Bojczak, who had to pay $US32,000 ($40,368) for interrupting signals at Newark Airport with a jammer he too was using to hide his location from his employer.

This is what can happen when technology built for — and still necessary for — high-grade military purposes becomes available to the general public for personal, and often petty, applications. People trying to avoid their annoying bosses end up taking out navigational systems everyone depends on.

The military has been planning for years to set up a more secure GPS system, but it is perpetually delayed. So instead the government is protecting this critical infrastructure by outlawing jammers. It doesn’t seem to be working.

I was leery of breaking the law to test my brand new GPS jammer, so I never used it, but I found people online willing to document their success. In a 2013 YouTube video, a man happily demonstrated how well his jammer worked and directed watchers to a site that sells them in exchange for Bitcoin. He plugged his jammer into a power outlet in his dashboard, causing the fleet-management tracking device in his vehicle to lose its GPS signal.

“Now they’re pretty hard to get ahold of because the feds are trying to restrict the sale and use of these things,” he complained. “I’m sure you can figure out why: They like to track us.” Last year, the FCC fined a Chinese company a record $US34 ($43) million for selling 10 jammers to undercover FCC agents.

Despite their illegality, the devices, which sell for around $US45 ($57), are widely available online, often from retailers based in China. I even found a few GPS jammers being sold on eBay, which is where I bought mine for $US42 ($53). (The FCC guidelines forbid the use, sale or manufacture of jammers, but not the purchase unless it’s “imported from a foreign retailer.”) When I searched for “GPS jammers” on eBay, most of the results were for sleeves to protect your phone from being tracked, but there were a few listings for “signal boosters.” The product descriptions made clear, however, that they are in fact the opposite — signal killers that can be used to “prevent car and people from being tracked.”

The product’s description on eBay

I went with the U.S.-based seller who’d been an eBay member since 2011 and who had nearly 200 positive reviews. After the seller shipped me the jammer from Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn, I reached out, identifying myself as a journalist, and asked to talk.

“This product purchased from China, we don’t know about this product,” the seller responded via eBay’s messaging system. “We have no stock. Please don’t call us.”

Ryan Moore, communications director for eBay, said GPS jammers are prohibited on the site and that sellers who circumvent eBay filters that prevent listings of these goods may have their accounts suspended.

“Additionally, we also work closely with the FCC who report them to us directly as well as the filters we have in place,” said Moore by email. “And, of course, any eBay user can ‘report an item’ on the listing page.”

To try to see the devices in use, Gostomelsky, who works for the security firm Spirent Federal — which, it should be disclosed, sells equipment designed to detect jammers — set up GPS signal monitoring equipment in his hometown of Philadelphia, in San Jose near the Spirent office, and briefly in Washington, D.C. His equipment is programmed for its particular location, locks onto 12 satellites, and starts listening; it knows a jammer is nearby when there are changes or interruptions in the signals being sent by the distant satellites.

He wanted to find out just how popular the forbidden devices actually are. In the course of eight months, the five stations he set up, which could detect unusual activity up to a mile away, detected GPS jammers 78 times, deployed by 19 different people or groups of people.

“It was about the number I expected,” said Gostomelsky, who is presenting his findings during a talk at the security conference Black Hat in Las Vegas at the end of July.

Some of the ways the jammers were being used, though, surprised him. While he was at the Washington Hilton in D.C. for the security conference Shmoocon in January, Gostomelsky’s station picked up on GPS interference in the area. Gostomelsky mounted the 9kg of hardware on his back and tracked the signal to a high school gym, inside of which kids were flying drones.

After someone landed a drone on the White House lawn in 2015, drone manufacturers like DJI began programming their flying machines to refuse to operate if they were in a “no drone zone” with a 48km radius around D.C. The kids apparently used a jammer to trick their drones into assuming they were outside the nation’s capital.

They aren’t the only ones who’ve had the idea of using GPS jammers for fun. According to reports on Reddit, cheating Pokemon Go players turned to the devices last year. The game overlays virtual creatures and arenas on the real world via a smartphone app; players have to go to those real world spots with their phones in order to collect creatures or to battle for control of the arenas, called gyms. One Reddit user said on the messaging forum that a “guy in his neighbourhood” bought a bunch of jammers and set them up near the real-life locations of the virtual gyms he had conquered in the game. That meant that when other players approached the gyms, the GPS on their phones would be blocked and their locations couldn’t be registered in the virtual space — which meant “nobody could conquer his gyms.”

Another Reddit user who said he was on the security team for an Australian aerospace company complained that Pokemon Go players were putting jammers around virtual gyms in airports and were affecting aircraft operations.

A Reddit message to that user went unanswered, so his identity couldn’t be verified, but Gostomelsky said the claim was plausible. “It would be expensive but technologically feasible,” he said. “If they were attached enough to the game and had money to burn, they could certainly do that.”

But most of the jamming Gostomelsky saw was done for the sake of profit or paranoia. Gostomelsky lives near Interstate 476 in Pennsylvania, and would regularly detect GPS jammers in use as tractor-trailers went through the toll booths. Because the toll-taking for commercial trucks relies on GPS tracking, they can avoid paying through jamming. If a $US45 ($57) device made your daily commute free, you too might be tempted to commit a federal crime.

Gostomelsky’s equipment fit inside a Pelican 1500 suitcase. He would put official looking stickers on the suitcases, for federal agencies that don’t actually exist, and then lock them to road signs to monitor passing cars.

Hacker at work

Gostomelsky wanted to be able to identify exactly who was doing the broadcasting, so he included in his five suitcases four microcomputers with software-defined radios — devices that decipher radio signals. These picked up on a variety of signals that might be travelling along with the jammer: the list of wi-fi networks and Bluetooth connections a device was programmed to look for; broadcasts being made on radio frequencies typically used by law enforcement and security guards; and the signals sent by tire pressure monitoring systems. The last one is particularly novel — car tires wirelessly broadcast a unique number to the car telling it if the pressure in the tires is getting low; his device picked up on that transmission, letting him identify particular cars.

“I’m stalking end users with the data they’re broadcasting,” said Gostomelsky.

Oftentimes it was obvious to Gostomelsky why a particular person was using a jammer. People driving company trucks wanted to avoid being tracked on their lunch breaks by navigational devices installed by employers (and they would tell Gostomelsky that when he walked up to the cars and knocked on their windows).

Stephanie Voelker, a product manager at Geotab, which makes fleet tracking devices, told me their devices note every time GPS connectivity is cut off. That would presumably alert the company when a jammer is in use, defeating the purpose and arousing suspicion. But cut-offs are not unusual; on a given day, 1 out of 10 of their devices experiences a signal loss. So the company has not historically detected jammer use until it spread through a fleet, resulting in lots of cut-offs. Geotab now includes a “privacy mode” on its fleet tracking devices in hopes that employees will use that instead of jammers to protect their movements.

Other jammer use-cases that Gostomelsky saw were more mysterious. A couple of jammers who were flagged by his system in Philadelphia had unusual electronic signatures emanating from their cars. They appeared to have both smartphones and burner phones, based on their communication with cell towers, which he was also monitoring. He was intrigued, so he started moving his listening stations around to figure out the cars’ driving patterns, to zero in on where these jammer users lived. He wound up tracking one of the jammers to a house in New Jersey. He went digging through public records to see who lived there and figured out the property owner was related to a police officer.

He is now convinced that some of the people using illegal jammers were police officers. They may not have seen a 2014 warning from the FCC that the prohibition on jammer use applies to “state and local government agencies, including state and local law enforcement agencies.”

“I think they’re using GPS jammers on their vehicles so that they can’t be tracked home,” Gostomelsky said. An undercover officer, for instance, might worry about a suspicious target sticking a GPS tracker under his bumper to find out if he’s a cop. A jammer would ease that concern considerably.

Gostomelsky didn’t actually knock on any doors to ask if that was the case, though, because “unnecessary encounters with law enforcement are not advised.” You never know — they may have appreciated learning that sometimes, a method to protect your privacy becomes a red flag that attracts attention instead.

The most active and enthusiastic GPS jammer in America is also on the government payroll, but uses the technology legally. It’s the U.S. military, which periodically jams GPS around bases for military exercises. For example, in 2016, it jammed GPS for 805km around White Sands in New Mexico for 3 days so that first responders from across the country could practice operating when their signals were jammed up.

The military sends out a “notice to airmen,” or NOTAM, when it plans to block GPS in an area, but pilots don’t always become aware of the problem until they find themselves flying satellite-blind. NASA’s Aviation Safety Reporting System has dozens of terrifying reports from pilots in recent years about their GPS being jammed and interfering with their aircrafts’ operation; the culprit is often the military.

In 2012, a Sacramento-bound MD-80 commercial airliner wound up 16km off course due to military GPS jamming. An air traffic controller noticed and contacted the pilot, who hadn’t noticed that his GPS was down. The controller reported that if the pilot had noticed and tried to get back on course, the plane might have collided with an eastbound plane seven miles away that was flying between the the correct and incorrect routes.

In a more recent incident in April, an Airbus A319 flying over White Sands was jammed numerous times while cruising. The pilots didn’t realise it, incorrectly believing that the signal interruption was caused by their GPS units resetting themselves. They didn’t realise they were without GPS until they tried to land. “Stop jamming commercial traffic,” the pilot wrote in his NASA report.

Last year, the military warned that it would be jamming GPS over a 805km zone emanating from a base in southern California for six days in June. The affected area included Los Angeles, San Francisco and Las Vegas. After aerospace groups voiced concerns about the plan, the military canceled the exercise.

The Register claimed the GPS blackout was needed to test a “Massive GPS jamming weapon.” A Navy spokesperson couldn’t confirm or deny that, saying the military doesn’t comment on what testing is for. But it’s more likely that it was simply to give soldiers exposure to what it would be like operating in a scenario where GPS signals were lost.

But using GPS jamming as a weapon does happen. North Korea periodically interferes with GPS using jammers mounted on trucks that it drives close to the South Korean border, causing navigational problems for aeroplanes, ships, and drones in the area — not to mention any GPS-guided missiles headed in its direction.

Closer to home, GPS jammers obviously remain a problem. From his research, Gostomelsky now has a list of people who illegally used them, with enough data about them to make it possible to track them down and prosecute them for “malicious interference to satellite communications.” But he’s not looking to get people into trouble.

“We’re destroying this data and keeping it anonymized,” he told me. “But there’s nothing to stop city officials from setting up a similar system.”

Nothing but inertia and perhaps some fear of having to prosecute their own police officers.

As for my own unused jammer, I’ve decided it’s not a good idea to keep it lying around. The FCC requests that anyone with a jammer voluntarily surrender it to one of their regional enforcement bureaus. I’m planning to take mine in this week. The enforcement bureau for San Francisco is an hour’s drive from my house. I’ll need GPS-driven directions to get there.

This story was produced by the Special Projects Desk of Gizmodo Media Group.