Fake health news can feel like an epidemic these days, but it was also rampant during the Victorian era, when bodily ailments were often a matter of life or death. But unlike the questionable remedies you may be familiar with — vaginal steaming for your cramps, or a float tank to chill your anxiety out? — some of the bogus ideas about wellness cultivated in 19th century England actually helped save lives, by bringing public health issues to the forefront.

Louis Pasteur, also known as “the father of microbiology”, didn’t prove that germs even existed until the early 1860s with his “meat-in-a-jar” experiments, and it wasn’t until 1879 that a German doctor, Robert Koch, linked specific bacteria to specific diseases. Once these basics were proven, the knowledge piled up quickly; by 1884, typhoid, tuberculosis, cholera, dysentery, malaria, tetanus, pneumonia and other common bacterial illnesses were connected to their unique microbes.

Cholera “Tramples the victors & the vanquished both”. Robert Seymour, 1831. Image: US National Library of Medicine.

Before that, health advice was a mixed bag of the silly (leave a bowl of water out to cleanse the air of “carbonic acid”) and the just-plain-wrong: The popular health manual Domestic Medicine suggested washing one’s body in order to make sure that pores were unblocked: Dirty skin disallowed perspiration, sending toxins deep into the body where they produced illness. (None of this is true, as anyone who has sweated through a layer of dust and dirt on a backpacking trip can tell you — but the false idea of “detoxing” via sweating has stuck around.)

The most spectacularly incorrect Victorian health idea was the belief that the aromatic assaults of city life weren’t just unpleasant, they were dangerous. Smells could kill via miasma, which caused disease. Author Lee Jackson, who wrote the disgustingly interesting book Dirty Old London, defined miasma for me as “a foul smell, particularly the stench of rotting matter”.

And that reeking, composting stuff? It was everywhere, and predictably, worst in the cities, especially the rapidly-growing metropolis of London. Chief among those odours was the stench of urea from men peeing everywhere (there were no public bathrooms, a fact which meant women did not stay away from home long, as very few women would condescend to micturate in the street). Other delightful notes in the urban aromatic profile came from “pigstyes”, garbage heaps of household waste on side streets that contained “cinders, bones, oyster-shells… decaying vegetable matter, putrefying fish, or a dead and decomposing kitten,” according to Jackson’s book.

Then there were the backyard cesspools filled with human excrement — yes, even well-to-do households had these, which were serviced by “night-soil men” who scooped the waste out in buckets, and sloshed through city streets with the human manure under the cover of darkness. Poorer families shared an often-overflowing cesspool that might be mucked out occasionally, depending on their landlord’s whims. There were no city regulations about how these cesspools were built, but their considerable fetor was the least of the problem: In London “the subsoil was becoming saturated with human detritus, and it began seeping through the earth to pollute the groundwater that fed the wells,” writes Ruth Goodman, a voluble DIY historian who has lived as a Victorian herself, and told the tale in the bestseller, How to Be a Victorian.

Vinaigrettes like this one (1701-1800) would hold strong-smelling items like a vinegar-soaked sponge for sniffing in smelly areas of the city to “prevent” disease. Image: Science Museum, London, Wellcome Images

And if you think it can’t get worse than raw sewage, how about putrefying dead bodies? In cities, graveyards were more like decomposing grounds, where bodies might be buried temporarily, depending on demand. In the small graveyards, most amidst neighbourhoods, newly dead would be buried on top of the older dead — sometimes the old bones were removed and stored in bone (or charnel) houses to make more room. Spa Fields, a popular burial ground, was “absolutely saturated with dead” by the 1830s. “London’s small churchyards were so ridiculously full, that decaying corpses were near to the top soil; ‘graveyard gases’ were a familiar aroma. In fact, gases from corpses are relatively harmless,” wrote Jackson in an email, but the smell of death was terrifying for many nonetheless.

Considering the horrors you’d smell on your daily walks in London, it’s understandable that the Victorians, surrounded by diseases with no cure like typhoid, cholera and tuberculosis, would be taken in by charlatan cures. A clean-up, by way of sewerage, cemeteries (an idea pioneered by the French to move dead bodies to the verdant, peaceful countryside for eternal rest — and quickly adopted by the English), public toilets, washhouses, and piped in water rather than wells dug next to cesspools, all reduced miasma. And with the smell, disease subsided, giving Victorian public officials all the proof they needed to keep adding utilities — which they continued to do apace, and for which they are now remembered as the inventors of “sanitary science”.

All that smart sanitation was based on the mistaken science of miasma. The health beliefs of influential figures such as Edwin Chadwick, who championed the “sanitary cause” in the 1840s and tirelessly argued that “all smell is disease”, led to very real improvements in public health for the lucky Victorians.

“It was an appealing idea — not least because the slums, where epidemics raged, stank. The building of a unified network of sewers in the 1850s-70s undoubtedly saved London from further epidemics of cholera and typhoid. It was done on grounds of ‘miasma’ but, regardless, the consequences were very positive,” said Jackson.

Belief in miasma was problematic in other ways, however. For instance, it was not only believed that miasma caused disease, but that the type of illness one procured had to do with one’s moral sensibilities and bad habits. It wouldn’t be Victoriana without a little victim-blaming, would it?

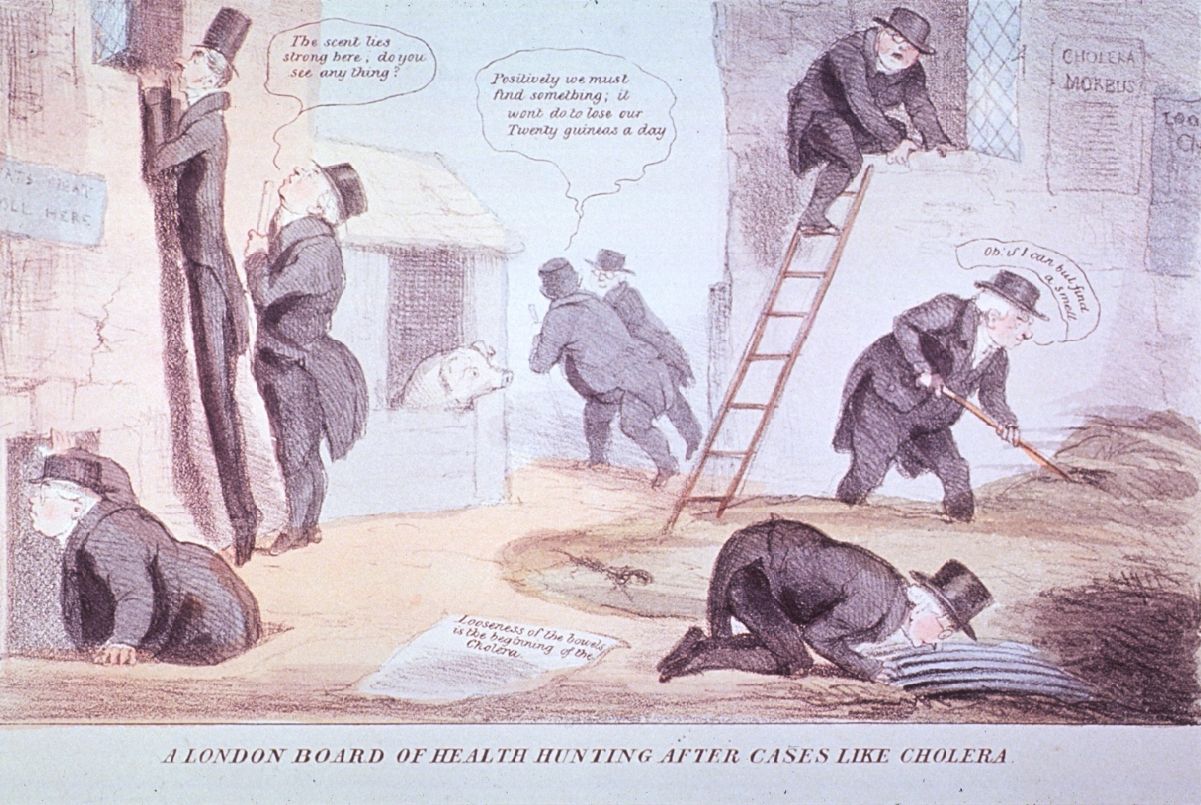

Image: Robert Seymour Robert, 1798-1836 via The National Library of Medicine.

“According to the old theory, the same evil miasma could be expressed in one individual as a lung disease and another as a stomach complaint, depending on their constitution and circumstances,” writes Goodman. The idea that somehow a disease stems from our mind-set, or can be cured by thinking positively, persists even today, despite being roundly disproved.

Indeed, a striking similarity between the Victorian era and modern times is that incorrect health ideas didn’t die easily.”Even once we did know the truth about disease vectors, the unpalatable truth is that there wasn’t a linear ‘march of progress’ during the Victorian era, and even the great scientific advances — such as John Snow’s discovery that cholera was water-borne — had little practical impact. Sewers, in particular, were built because of a fear of ‘miasma’, not because of Snow’s breakthrough,” said Jackson.

Today, fake science usually means ineffective treatment, or worse — it causes death. But in at least one case in the Victorian era, it actually saved lives, and ushered a new era of sanitary living that most of us are a part of today.