Living under racism as a black person makes one constantly ask themselves questions, chief amongst them, “What are non-black people seeing when they look at me?” and its corollary, “How much should I care about that crap, anyway?” Get Out dredges up the answers you already know in the goriest possible form.

Image bu Taj Tenfold via Get Out official site

Written and directed by Jordan Peele — best known as one half of the eponymous duo from Comedy Central’s Key & Peele series — Get Out is a movie that transmutes subtext into text. At its core is the months-old relationship between black man Chris Washington (Daniel Kaluuya) and white woman Rose Armitage (Allison Williams). The film opens as the interracial couple are getting ready to travel up to her family home in a lily-white, upper-middle-class enclave. The Armitages welcome Chris with a full suite of well-meaning liberal elite awkwardness, complete with changed-up speech patterns and heartfelt declarations of fealty to Barack Obama.

When the family’s annual gala brings moneyed guests from all over, the elites hover around Chris and subject him to all sorts of bizarre appraisals. They squeeze his bicep and ask him whether he thinks he has any advantages as a black person in America. It’s all foreshadowing for the movie’s big twist: The Armitages have been kidnapping and hypnotising black people for years so that old rich white folks can live inside their darker bodies.

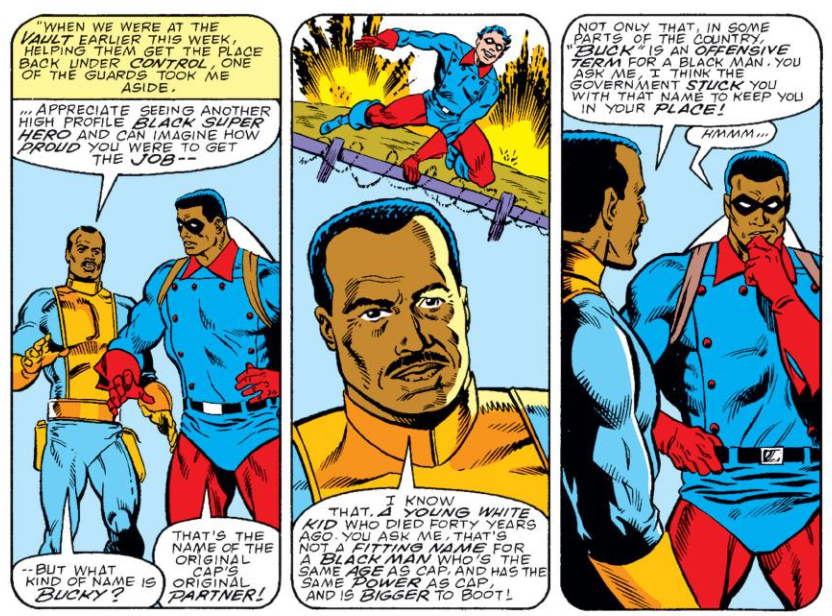

The first significant bit of foreshadowing in Get Out happens when Allison hits a deer on the way to her parents’ tucked-away estate. Chris is shaken at the sight of the dead animal. Later, Rose’s dad goes on a rant about hating deer, saying he wishes he could just kill all of them. “Hey, a male deer is a buck,” my brain free-associated, and that train of thought reminded me of the time Marvel Comics unwittingly messed up an effort to diversify its superhero population. Nearly 30 years ago, Steve Rogers gave up being Captain America after deciding he couldn’t just blindly follow orders like the US federal government wanted. His replacement in the red-white-and-blue uniform was super-strong wrestling malcontent John Walker. Walker’s partner was a black man named Lemar Hoskins, who would be operating under the Bucky codename originated by Steve Rogers’ teenage WWII sidekick. Unfortunately, writer Mark Gruenwald only learned that “buck” was a dehumanising term for black men after the story was already in print.

Image from Marvel Comics’ Captain America #341

Hoskins’ superhero name was later changed to Battlestar and reader complaints were voiced by a character in the continuing storyline, but the incident was a glaring corporate case of “you gotta get a black friend”-itis.

Watching Get Out induced other rapid-fire flashbacks for me, like the semi-drunken epiphany I experienced about 10 years ago. I posited the idea that black people lead the most annoyingly metaphorical lives in America, where it seems like everyone’s watching and no one’s caring. “Wha-whuh-whadooomeenbydat,” asked the friend I was hanging with. “Whenever we’re in a physical or cultural space, the meaning gets multiplied and we have to carry the extra weight. If we’re the first, last, majority or minority to do something, it has to get unpacked. Shit is exhausting. Extra work we don’t get paid for and we’re supposed to be happy about it because we’re ‘special’.”

The nature of the “specialness” imparted to black people in America is wildly dysfunctional. I’ve experienced it firsthand. I’ve been in relationships where I’ve been told “my parents can’t know about you… ever”. One time, after meeting me, a girlfriend’s boss wondered aloud, “He’s a biiig guy, huh?” to her face. As a teenager, I got stopped by cops for walking through a nicer, whiter neighbourhood. When I told them I was going to the library — my teachers encouraged me to push myself in my reading, you see — they smirked sceptically at me. I felt like I was standing outside of my own body in those moments, a vessel for interpretations I had no hand in shaping.

Peele opens up that bleak vein of the American body to let comedy that’s dark like venous blood drip all over Get Out. He sardonically invokes hoary old horror-flick genre conventions — the weird groundskeeper, false innocence, “it’s all in your head” mind games — and re-purposes them for cutting commentary. In the middle of the movie, Chris gets hypnotised, knocked out and tied up so a rich white man’s brain can get transplanted into his young, talented body. In the creepy rec room where he’s held captive, a mounted buck head stares lifelessly back at him. When he gets free, that buck head becomes an antlered weapon that helps Chris stab a bloody path to freedom. Chris is a “buck” using a buck killed by a rich white man to kill the rich white man that was going to steal his life.

Similar moments all over the film skewer America’s centuries-long fetishisation and commodification of black creativity and black bodies, as critic Greg Tate wrote about in Everything But the Burden: What White People Are Taking From Black Culture. The victims that we see are black creatives; Chris is a photographer and Dre (played by Atlanta‘s Lakeith Stanfield) is a jazz musician. Rose is shown looking up NCAA prospects as a pool for future targets. It’s a fascination that gets specifically executed in a formula that doesn’t threaten white supremacy.

Kaluuya’s performance is at turns wary and vulnerable, making you believe that his need for love would blind him to the danger coalescing all around him. You also get the sense that Williams was cast as Rose as a comment on the kinds of characters she plays elsewhere. But it’s Lil Rel Howery’s turn as Chris’ best friend Rodney that steals the show in Get Out. He’s the living embodiment of a black comedic tradition that lampoons what the overwhelmingly white characters do in horror movies.

His frantic advice to Chris is the ignored warning that something’s wrong. Cutting off the two friends’ connection is part of the Armitages’ machination to capture Chris, as well as a way of dealing the horror-genre mobile phone problem. You can also read that plot beat — which has the housekeeper repeatedly unplugging Chris’ phone so it doesn’t charge — as a symbolic nod at a collective fear of the power of black people supporting each other.

Touches like these make Jordan Peele’s film is a master-class trickster work, a cultural production that brings knowledge and experience to light by mocking and subverting the power structure it occurs in. Get Out turns the idea of what a “bad neighbourhood” is on its ear and drives home the chilling fact that, if you’re a black person, the mere words of a white person can become the ultimate violence that nullifies your self.

Get Out premieres in Australia May 4.