In December, the headlines were euphoric: After a deadly West African Ebola epidemic two years ago, scientists had not only developed a vaccine, but it appeared to be 100 per cent effective. That effectiveness was quickly disputed — but now, as a new Ebola outbreak is rattling the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the vaccine may finally get a crucial real world test.

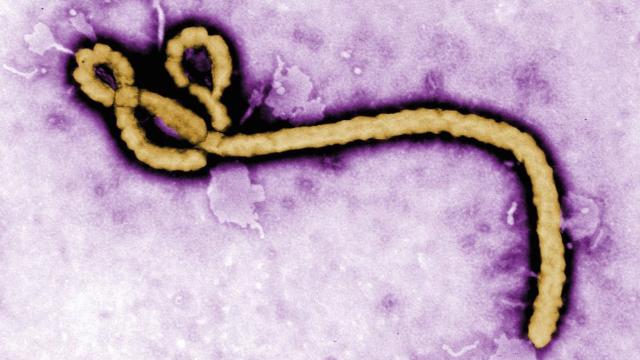

The Ebola Virus. Image: Getty Images

In April, several months after an Ebola vaccine was announced to much fanfare, a panel of scientists from the US National Academy of Medicine challenged the methodology of the vaccine’s 4160-patient trial in Guinea. In a 287-page report, they ultimately concluded that while the vaccine “most likely provides some protection to recipients”, that protection “could in reality be quite low”.

Now, an Ebola outbreak in the DRC might be the vaccine’s ultimate proving ground. So far, there have been two confirmed cases and 17 other suspected ones, with three dead among them, according to the World Health Organisation. On Monday, the organisation said that it is now making preparations to use the controversial vaccine, though it has not yet made a firm decision on whether to deploy it.

The number of suspected cases is so far small, especially given that the outbreak has so far not been identified beyond a remote, isolated area. But it took three weeks for experts to identify the disease, meaning it could have already spread much more widely than is presently known. And Congo’s healthcare system ranks among the worst in the world.

There are some 300,000 emergency doses of the new vaccine on hand, should WHO and others decide it is necessary. The vaccine was developed by the pharmaceutical company Merck and NewLink Genetics. In December, doctors from the World Health Organisation, Doctors Without Borders and others reported in the medical journal The Lancet that the vaccine was 100 per cent effective at preventing people from contracting Ebola’s deadly hemorrhagic fever once it kicked in, when tested during the West African epidemic. That outbreak saw more than 28,000 Ebola cases and more than 11,000 deaths.

The subsequent National Academy of Medicine study took issue with the vaccine study’s methodology. Researchers conducted a randomised trial in the midst of the epidemic, a decision which raised ethical concerns about giving people at risk of dying a placebo. But instead of randomising people, it randomised groups of people who been in contact with a person with Ebola. Some clusters received a vaccine immediately, and others after 21 days, the longest time frame which it takes someone to show signs of Ebola.

In the first group, they reported were no new cases. In the second there were 16. But because the researchers estimated it would take 10 days for the vaccine to even kick in, they discounted cases that cropped up within 10 days of being vaccinated — but people did get ill before that 10 day period. When including cases contracted within that initial 10 day window, 20 of 3232 participants got Ebola in the immediate-vaccination rings, versus 21 of 3096 who received the delayed vaccination.

Reading the data differently, in other words, suggested less effectiveness. Not to mention that in the immediate-vaccination rings, one-third of the people slated to get the vaccine declined, throwing another wrench into the analysis.

It’s clear that the vaccine did have some positive effects. But it’s unclear how effective it really is, meaning that it may not be the great firewall against Ebola necessary to contain an outbreak.

There are now 12 Ebola vaccines in development, and the Merck vaccine is the furthest along. In April, WHO’s advisory group on immunisation recommended that the vaccine be deployed promptly should another Ebola outbreak occur. The vaccine only appears to work against one of the two common strains of Ebola, but that appears to be the same strain present in Congo now.

The Congo outbreak in all likelihood will not come close to approaching the levels of the West African crisis — the worst Ebola outbreak in history. In Congo, the last outbreak killed 49 people over three months. Much of Congo is hard to access, with bad roads, dense forests and isolated villages. That means it’s hard for the virus to get very far.

If the vaccine is deployed, though, the same ring vaccination strategy used in the Guinea trial will likely be used here, offering vaccines to all people who might have been in recent contact with a newly diagnosed Ebola patient. If things escalate to that point, it could be a critical test.