For years, a debate has raged among scientists as to which ancient creature represents the first true animal, sponges or jellies. Using a new genetic technique, a collaborative team of researchers has concluded that ctenophores — also known as comb jellies — were the first animals to appear on Earth. It’s an important step forward in this longstanding debate, but this issue is far from being resolved.

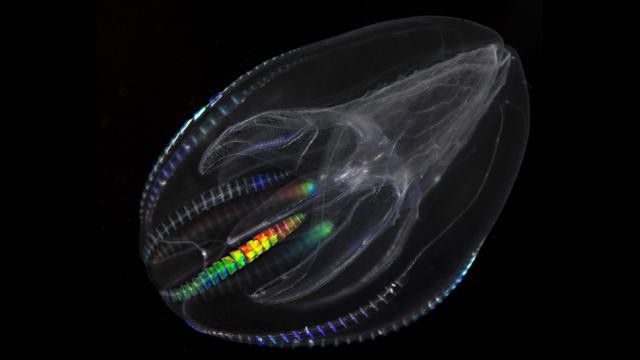

Comb Jelly. (Credit: Stefan Siebert/Brown University)

A new paper published in Nature Ecology and Evolution suggests that ancient jellies, and not sponges, represent the oldest branch of the animal family tree. The Vanderbilt University and University of Wisconsin-Madison researchers who conducted the study aren’t the first to make this claim, but they used an emerging technique to parse literally hundreds of thousands of genes, showing that comb jellies have the most ancient genome of any animal. The researchers say the method could be used to resolve other longstanding issues in evolutionary biology, but given the highly interpretative nature of their findings, it’s likely the sponge-versus-jelly debate will continue to rage on.

Decades ago, scientists slotted animals on the so-called “tree of life” by eyeballing organisms, designating the ones that appeared to be simple as more primitive in terms of their evolutionary standing. Things changed with the advent of genomics, when scientists gained the ability to read and compare the DNA of organisms and classify them accordingly. This new field, called phylogenetics, has revolutionised the way we define evolutionary relationships, but many gaps exist among the numerous branches in the tree of life — including the very first trunk at the base of the animal tree.

Traditional phylogenetic techniques have resolved about 95 per cent of all evolutionary relationships, but an irksome five per cent of cases remain unresolved, leading to controversies. To understand why certain relationships in the tree of life continue to be controversial, the authors of the new study took a look at pre-existing data sets, and compared the individual genes of jellies and sponges to finally come up with what they believe to be the world’s first animal.

“To figure out why [these controversies persist], we specifically examined the two best-supported alternatives for a series of controversies and noted how many genes support one over the other alternative,” explained lead author Antonis Rokas in an interview with Gizmodo. “When we applied our approach to the jellies/sponges question, we found that all available data sets — eight [phylogenetic data sets] so far — favour jellies over sponges.”

During their analysis, the researchers compared the individual genetic markers of sponges and jellies, which numbered into the hundreds of thousands. Each time a gene favoured one hypothesis over the other, it was labelled a “phylogenetic signal”.

“When you look at a particular gene in an organism — let’s call it A — we ask if it is most closely related to its counterpart in organism B? Or to its counterpart in organism C? And by how much?,” said Rokas. By going about their analysis in this way, the researchers had more confidence in their ability to orient species on the tree of life. Simply put, this method led to the discovery that comb jellies have considerably more genes to support their status as the first animal. Both sponges and jellies emerged at least 500 million years ago, and maybe as long as 700 million years ago. This latest research suggests that sponges evolved from jellies, but that’s still a matter of contention.

“So, what’s novel in our study is that we’ve found a way to quantify the support for the two alternatives across several different previously generated data sets and find them all in support of jellies first,” said Rokas.

Using the same technique, the researchers were able to resolve another 14 taxonomic conundrums, finding, for example, that crocodiles are more closely related to birds than they are to turtles.

So does this settle the sponges versus jellies controversy once and for all?

“I don’t think so,” admitted Rokas. “Some of the controversies that we’ve examined, including the jellies/sponges one are devilishly difficult to decipher; we’re trying to figure out the order of two events that happened in close proximity a long, long, long time ago. So it’s tough!” That said, Rokas hopes that the general approach and methodology that his team used in the study will shed more light into the nature of these controversies, which ultimately may pave the way for their resolution.

Part of the challenge is the sheer amount of genetic data involved in phylogenetic analyses, and how that data is interpreted. Just days ago, a similar study was published in Current Biology, in which the biologists used “an unprecedented array of genetic data” to reach a very different conclusion, siding with the sponges-were-first camp. Rokas hasn’t had an opportunity to investigate the rival research in too much detail, but he says the two studies differ in the data sets examined and in the statistical methods used.

Joseph F. Ryan, a biologist at the University of Florida who wasn’t involved with the study, agrees that the debate is far from resolved.

“The beauty of these controversies is that besides engaging the public they motivate researchers to look closely at how we build trees,” Ryan told Gizmodo. “We have learned a lot in the past ten years or so regarding the best way to analyse these data, but clearly, as this study shows, we are still at an early stage in terms of methods.”

While it’s undoubtedly frustrating for the scientists, it’s actually pretty cool that we still don’t know the answer to one of the most fundamental questions in biology: Who’s our oldest living relative? Honestly, it’s kind of mind-blowing to know that we’re related to either of these organisms.