Fangblennies are tiny reef-dwelling fish only 5cm long that look like they came from some adorable deep-sea vampire movie. Only, if you’re a predator and you piss them off, they will wreck the crap out of you with their opioid-laced venom.

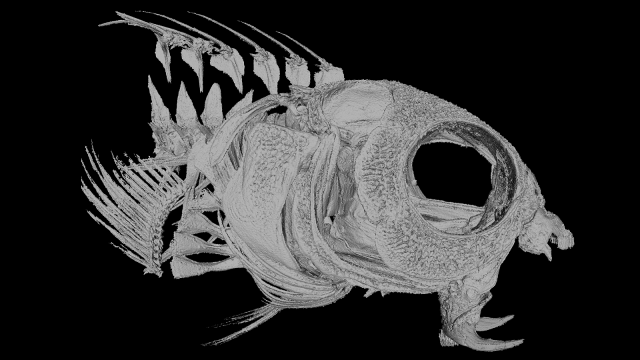

Micro CT scan of a fangblenny (Casewell et al)

An international team of scientists wanted to know how venom evolved in these little fish — there hasn’t been a whole lot of research into fish venom, as opposed to insect or snake venom. They discovered something pretty wild: That the fish attack predators with a venom that acts on animals’ opioid receptors, the same ones activated by opium-based drugs. But the story gets weirder than that.

“This study showed that the venom delivery system, the big fangs, evolved before the venom did,” study author and venom expert Nicholas Casewell from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine told Gizmodo. “Usually we find some sort of venom-y secretion before [fangs] evolve, and the animals get much better at delivering it. We found the opposite in fangblennies.”

Image: Anthony O’Toole

There are five genera of fangblennies, but only one with venom. The fish tend to eat plankton and algae, said Casewell — they’re not using their big fangs to catch prey. Instead, the fangs are for protection and to scare off predators who might try to mess with them.

For the new study, Casewell and his colleagues used microCT scanning and other forms of microscopy to image the fish. They also analysed their genomes and separated the kinds of proteins and peptides (protein building blocks) in the venom by running them across a gel using an electric current. The venom contained well-known enkephalins, proteins that activate opioid receptors, according to the research published today in the journal Current Biology. Provoked fangblennies literally inject opioids into predators who scare them.

What if humans attacked people with syringes full of opioid for self defence? Just a thought…

“[Opioids have] been found in the venom of a scorpion previously, but we weren’t expecting to find them in fish venom by any means,” said Casewell. “The venom causes a drop in blood pressure probably from the presence of these peptides. The strong drop in blood pressure is probably how fish are escaping their predators when they’re using venom.”

Image: Richard Smith

Fangblenny venom contains plenty of other compounds too, including one that might cause inflammation, and a potential neurotoxin. The fish inject their venom through glands beneath their teeth, and might be able to deliver more simply by biting harder, Casewell hypothesised. The fish’s evolutionary history and its appearance revealed that its venom evolved after its teeth.

Other scientists were impressed by the study. Kevin Arbuckle, a researcher from Swansea University in Wales, was especially surprised that the venom delivery evolved before the venom — he thought this could be a first. However, Peter Hundt, an assistant professor at St Cloud State University in Minnesota, wasn’t shocked by this. “Almost all blennies,” venomous and not, “have two different types of teeth,” canines and feeding teeth, he told Gizmodo. In other words, all of the fish have the machinery, and some just happened to evolve venom, too.

Image; Patrick Randall

And the teeth are important for other reasons. Casewell said that even fangblennies without venom might use their fangs for defence, the same way other fish have big spines that make them difficult to eat. He also thinks 15 to 20 species of fish have evolved to look like venomous fangblennies to protect themselves from predators.

The biggest impact of the new research is how it shines a spotlight on fish venom in general. “This paper is particularly exciting in that there are surprisingly few studies of venomous fish at all, despite them being one of the most diverse groups of venomous animals we know,” said Arbuckle. And why is that? Casewell guessed that “most of the research tends to be on animal that are dangerous to people — snakes and spiders are life threatening”. Fangblenny bites don’t cause much harm to humans.

Ultimately, the scientists behind the new study hope for more research into fish venom, as well as the chemicals it contains, which could include compounds useful in pharmaceuticals.