What makes a monster? It’s the central question at the heart of the disturbing indie flick The Transfiguration, which managed to horrify me in ways that I wasn’t expecting — even from a horror movie.

The Transfiguration is a meta-deconstruction built on the bones of other movies that have tried to render the vampire myth down to its barest elements. In the film’s very first scene, you learn exactly what teenage protagonist Milo is. He’s in a bathroom stall, leaning over and sucking blood from a hole in a dead man’s neck. It isn’t clear that Milo needs to be doing this to live. But he certainly thinks he does.

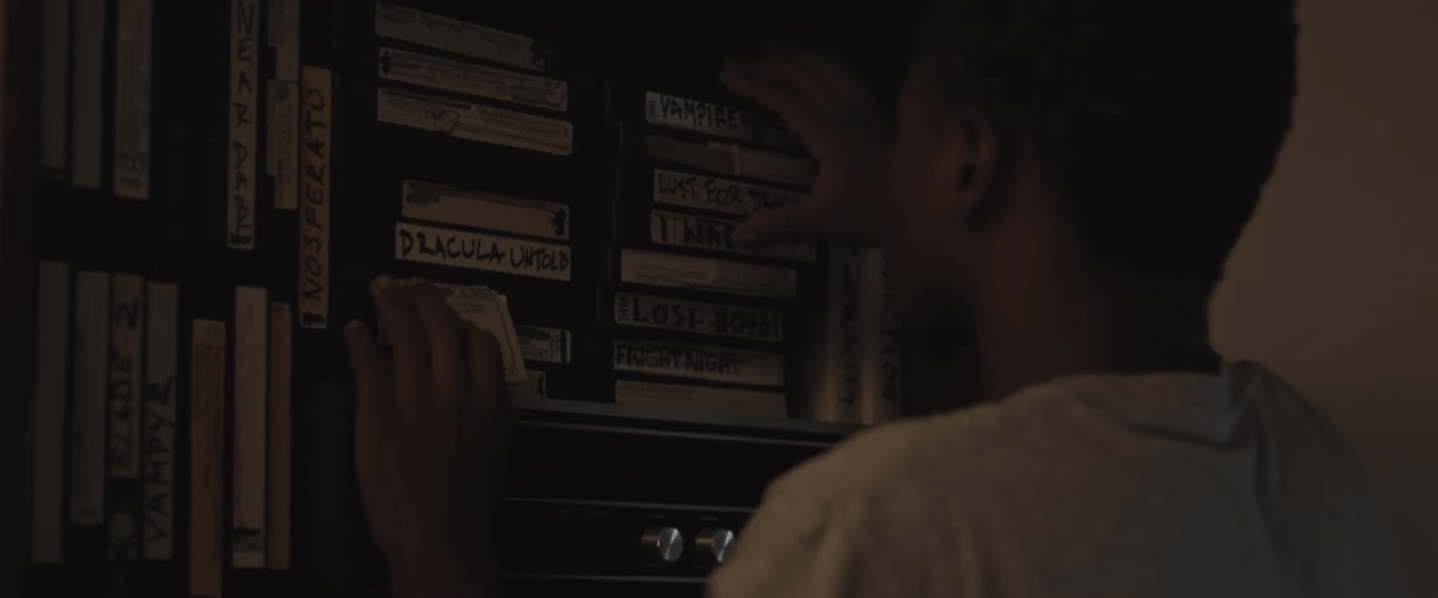

Written and directed by Michael O’Shea, the movie rides the tension of whether or not Milo is really a vampire. Is he a teenage boy who just kills people and drinks their blood or does he have the curse of the ages upon him? Milo lives with his older brother in a New York City housing project and walks around with a blank face and minimal affect. Despite his neutral demeanour — or maybe because of it — Milo gets bullied and teased by local thugs. He watches vampire movies religiously, along with videos that show how predators stalk their prey, and hides a stash of money behind a stack of VHS copies of genre classics like Nadja and Near Dark. Scenes with a school counsellor reveal a past where he’s harmed animals, and he’s shown meticulously working out his own bespoke headcanon about how vampires might work.

Milo’s life changes when a teenaged girl named Sophie moves into the building where he lives. Right after we first see her, she’s shown having sex with one young man while a group of his friends watch. The encounter ends with the boys laughing at her, and she cuts herself on purpose “just to feel something”. She shares a bottle of cheap liquor with Milo when he walks over but he’s far more interested in the blood running down her arm. After asking to see the wound, he pulls her arm toward his mouth as if in a trance. Grossed out, Sophie yanks her arm back.

Weird meet-cute aside, the two outsiders quickly start spending time together, sharing grim details from their young lives. Sophie’s parents are dead and the grandfather she’s moved in with is physically abusive. Milo’s mother ended her own life by slitting her wrist — a chilling flashback scene shows him sliding a finger in the congealing blood and bringing it to his lips (seen up top) — and he’s never directly dealt with how that’s affected him. Sophie asks Milo if he’s ever thought about suicide. He replies “I can’t kill myself… it’s against the rules,” and the mystery about what he is deepens even more.

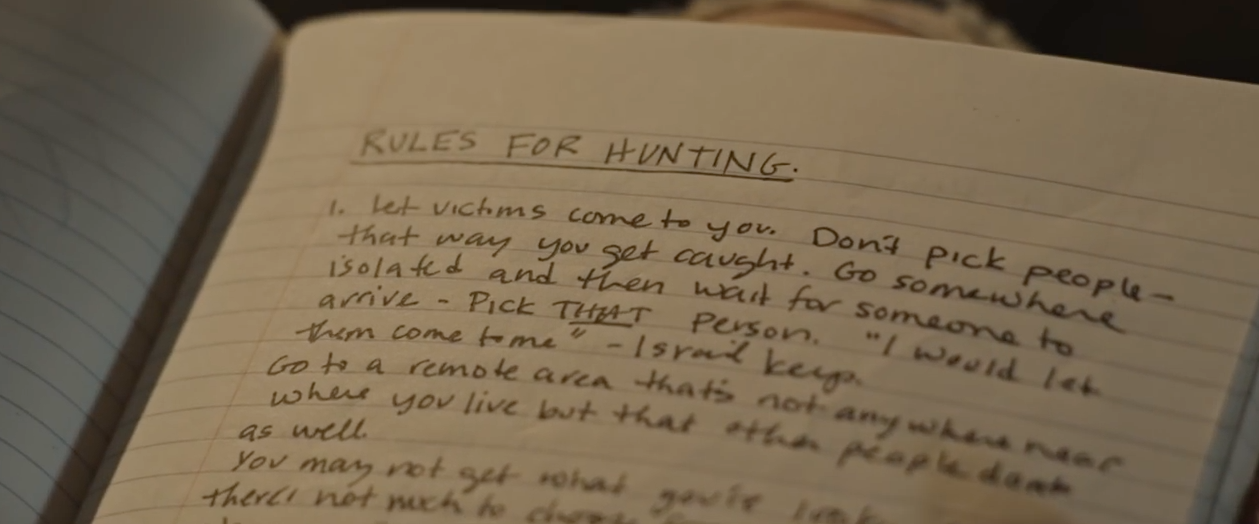

Stellar performances from Eric Ruffin as Milo and Chloe Levine as Sophie make the two kids seem uncomfortable in their own skins. While Milo gets a gruff sort of caretaking from his older brother, the teens’ truest emotional tether is to each other. Things blossom into an awkward first love, complete with Faces of Death and Nosferatu movie dates. Sophie tries to bond with Milo by saying he should read the Twilight books, but he says he prefers more “realistic” takes on bloodsuckers like Let the Right One In. But their relationship stalls when Sophie discovers the notebooks where Milo encodes the guidelines of vampire existence and the calendar where he’s been tracking his kills.

There’s an unholy stillness all throughout The Transfiguration. It’s filled with uncomfortable stares that are held too long, silences that scream with tension waiting to be broken, and terrifyingly intimate violence. Arguably, only one of Milo’s victims deserves to be killed and one definitely doesn’t. Milo sometimes throws up after drinking blood but we’re never sure if that’s because he is or isn’t a vampire. Ruffin portrays Milo with a creepy patience that makes his inner concerns inscrutable, and we don’t learn how he feels about his own existence until the very end of the movie, which gives the answer that the audience has been waiting for.

The ice-cold approach O’Shea takes toward Milo gave my stomach knots every time the main character killed someone. The Transfiguration feels like a throwback to 1970s grindhouse horror but feels retrograde in another, more disturbing way. The character construction of Milo, a poor kid who lives on the fringes of society and ends lives with remorse, rubs up uncomfortably against John J. Dilulo’s specious ideas about inner-city superpredators that became part of political discourse in the 1990s, as discussed by The Root:

On the horizon, therefore, are tens of thousands of severely morally impoverished juvenile superpredators. They are perfectly capable of committing the most heinous acts of physical violence for the most trivial reasons (for example, a perception of slight disrespect or the accident of being in their path). They fear neither the stigma of arrest nor the pain of imprisonment. They live by the meanest code of the meanest streets, a code that reinforces rather than restrains their violent, hair-trigger mentality. In prison or out, the things that superpredators get by their criminal behaviour — sex, drugs, money — are their own immediate rewards. Nothing else matters to them. So for as long as their youthful energies hold out, they will do what comes “naturally”: murder, rape, rob, assault, burglarize, deal deadly drugs and get high.

Milo does terrible things that are meant to be interpreted as the workings of a supernaturally traumatised mind. O’Shea’s film is texturally flat on purpose, so as to make its happenings all the more chilling. But that flatness makes it difficult to read. Is the marriage of the vampire and superpredator myths a purposeful one? If it’s intentional, the film’s ending makes it harder to pull out a larger meaning from that fusion. I know that this reading is something I’m bringing to the film; I just wish the movie itself didn’t make it so easy to do so. It’s the kind of problem that would be solved by more inclusivity in the entertainment industry.

The Transfiguration is a great movie that explores what it means to lose oneself in the ideas that power the horror genre, but it’s impossible, for me, to see The Transfiguration and not think about racial stereotypes and their onscreen history. My discomfort isn’t enough to wave anybody off from seeing the movie but I would have enjoyed it more without having to wonder about this uncomfortable echo.

The Transfiguration opens in New York City on April 7 and in Los Angeles on April 21. An Australian release date has not yet been announced.