If someone applied to a top position at a company, you’d hope a hiring manager would at least Google the applicant to ensure they’re qualified. A group of researchers sent phoney resumes to 360 scientific journals for an applicant whose Polish name translated to “Dr Fraud”. And 48 journals happily appointed the fake doctor to their editorial board.

Image: Internet Archive Book Images/Wikimedia Commons

This sting operation was the first systematic analysis on editorial roles in science publishing, adding concrete evidence to a problem past stings have shed light on. There are a whole lot of “predatory” scientific journals out there, journals that take advantage of scientists’ need to produce articles by publishing anything for a fee, without checking to make sure the paper is actually new research, worth publishing, and not completely inaccurate. But the problem is more than a juiced-up email scam (despite some probably-predatory journals looking essentially the same), and highlights many issues in today’s scientific publishing industry. Those issues can result in important science not being published in real journals, or worse, bad, un-vetted science being published, scientists bolstering their resumes with crap, and an eroding public trust in science as an institution.

“What this boils down to is that scholarly papers published in these types of journals are far less likely to have undergone any kind of quality check, including proper peer review,” one of the scientists leading the sting from the University of Sussex, Katarzyna Pisanski, told Gizmodo in an email. “It could result in (and probably already has) thousands of scientific articles that have essentially gone ‘un-checked’… If we cannot trust the academic publishing system, who can we trust?”

The standards of academia require scientists to publish papers. It’s how many get their PhDs, and how universities judge the quality of their research. Most journals say they thoroughly vet their research through peer review, by having knowledgeable subject matter experts look over the work and make suggestions before publishing. Some, like Science and Nature, charge a subscription fee to access their articles. Others, like PLoS One and Peerj, are open access, meaning that scientists pay a fee to have their work appear in the peer-reviewed journal, but the articles are free to read and access for anyone.

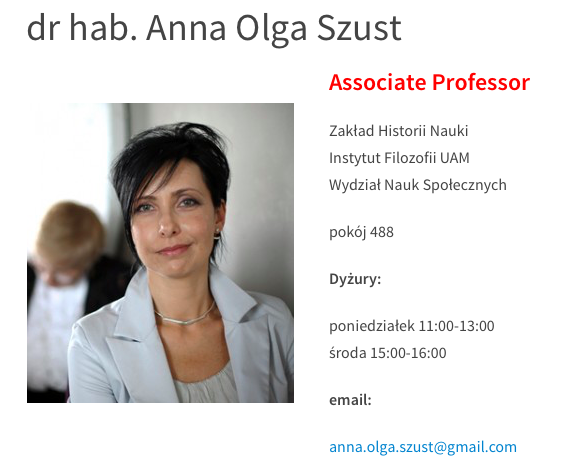

The idea for a sting operation came after the paper’s authors began noticing “absurd number” of emails asking them to send papers or be the editors of journals outside their expertise, said Pisanski. The researchers randomly selected 120 papers each from three sources: Jeffrey Beall’s blacklist, a since-removed list of predatory journals; the Directory of Open Access Journals (which is exactly what it sounds like); and titles indexed by Journal Citation Reports, which gives “impact factors”, a flawed but frequently-used metric that ranks journals and how often their articles are cited. The researchers created a fake web presence for their “doctor”, along with a fake resume listing fake research publications and no editorial experience. A third of the journals from Beall’s blacklist accepted Dr Fraud as an editor. Seven per cent of the DOAJ’s journals did, but none of the JCR’s journals did.

This may be the first peer-reviewed analysis of predatory journals, but scientists and others have been aware for the problem for a while. In 2013, journalist John Bohannon sent over three hundred nearly identical bogus papers to open-access journals, around 60 per cent of which accepted the paper without peer review, and published his results in Science. The problem hasn’t gotten better, Bohannon told Gizmodo. “I’m confident there are more predatory journals today than there were a few years ago,” he said.

I sent an email to the editor of one of the Society for Science and Nature journals, the fishy looking website below whose journals are probably predatory, given its appearance, buzzwords and content. I had not yet heard back at time of writing.

So what’s going on? There are lots of theories, but basically, scientists need to publish, and more journals than ever are open-access. Predatory journals are predominantly open access, pointed out Bohannon. Their publishers take money from scientists who are either gullible or just looking for a quick way to tie a publication to their name. Bohannon thinks the open access community needs to work to rid itself of these journals. “Finding bad guys in the world of open access publishing is something you should do if you love open access publishing,” he said.

That being said, some folks I spoke to, including Beall and people in the open access community, thought it was a larger problem than open access publishing alone. The community tries to regulate itself after all, Andrew Wesolek, head of digital scholarship at Clemson, pointed out to Gizmodo. The DOAJ removed 39 of the 120 journals listed in its directory before the analysis came out in Nature today, though six of the eight journals that accepted the fake editor still remain. When I called Lars Bjørnshauge, their founder and managing director, he immediately asked to be put in touch with Pisanski so he could find out the titles of the six journals. He said the DOAJ removes journals with fake editors immediately. “We go in and check randomly members of the editorial board and contact them to see if they are real people. On and off we actually discover an academic who says, ‘Oh, am I on the board of that journal? I didn’t know that.’ This is immediately cause for rejection or removal of that journal.”

Does this look legit to you? (Image: Screenshot)

Wesolek noted that many of the DOAJ’s journals don’t charge their authors fees, either. “It’s not correct to say that Open Access gives rise to a predatory model,” he said. Instead, “A business model, authors paying to publish, can potentially give rise to this problem.”

Bohannon said this business model reason to be vigilant in protecting the open access movement from exploitation.

Some think a whitelist of non-predatory journals would be a worthwhile solution, but others hope to see a reincarnation of Beall’s blacklist of predatory journals, including Beall himself. “Everyone figures out the easiest journal [to publish in] on the whitelist and then publishes there,” Beall told Gizmodo. A flood of scientists hoping to publish papers could turn the higher acceptance rate journals on the whitelist into predatory ones. Instead, Beall’s blacklist had been a resource to those wondering which journals were legit, but has been taken down for reasons Beall can’t disclose aside from pressure from the University of Colorado, where he works. He hopes to see a new blacklist take its place. “You can immediately eliminate these journals from the journals you’re going to submit to.”

Beall said he would also be alright with one of our suggestions — sting operations conducted by private agencies — but not if they were carried out by researchers. Fraudulently applying to journals still operates in a moral grey area, going against scientists’ honour codes, but might be OK for a journalist or a private investigator.

Aside from a blacklist, others recommend conversations on how to determine a journal is legit. “With time and experience most scholars acquire an almost ‘implicit’ understanding about what constitutes good science. They learn about reputable journals from mentors and leaders in their field,” said Pisanski. “But this takes time, and so students and early career researchers are encouraged to talk with others on this topic early on.”

But researchers in other countries not used to speaking English (though that’s the language most scientific publishing happens in) might not immediately recognise the difference between a predatory journal and the real thing, Bohannon and others said. Or they might recognise it and publish anyway to build up their cred.

This all might sound like inside baseball, but it can have tangible effects on non-scientists, as well. Two years ago, Bohannon wrote an article detailing how he submitted an accurate but purposefully bad study to predatory journals like these, who accepted the article. The story, on the immensely clickable topic of how chocolate can help you lose weight, made it to the press, and some journalists wrote stories with splashy headlines and little vetting. In 2017, we’d probably call that “fake news”, even if the story was based on a real paper.

Not only are predatory journals misinforming the public, they’re making the scientific institution as a whole look bad, and now more than ever, the public needs to be able to trust scientists.

Really, the problem probably just lies in the nature of publishing as a mark of scientific achievement. “I think efforts to de-emphasise publishing over all other forms of science productivity would go a long way towards cutting the oxygen supply of predatory publishers,” Adam Marcus, cofounder of science watchdog blog Retraction Watch and managing editor of Gastroenterology & Endoscopy News, told Gizmodo. These publishers could simply be “stepping in to meet this insatiable demand for journal articles”.

That’s Pisanski’s hope, too. “We — the academic community — need to de-incentivise contributions to low-quality journals that do not promote best practices and exist primarily to make money.”

[Nature]