Since early 2016, a NASA-employed Science Definition Team (SDT) of 21 researchers has been crafting a plan to send a robotic probe to Europa, an icy moon of Jupiter, located over 390 million miles from Earth. On February 7, that team delivered their first report to NASA, detailing their recommendations for that future mission, which will search for life by drilling toward the subterranean ocean scientists strongly suspect to exist beneath the icy moon’s surface. The team hopes to launch as soon as 2031.

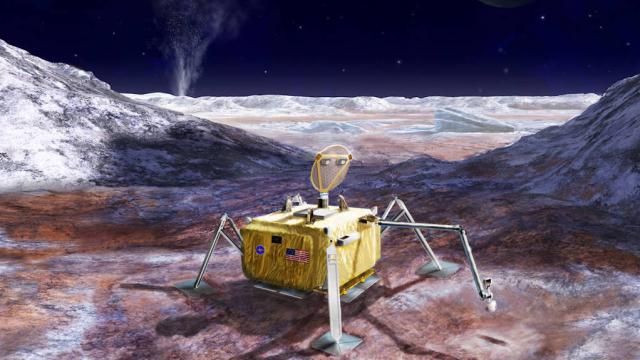

Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech

This is not to be confused with NASA’s Europa flyby mission, which is slated to take place in the early 2020s. That said, the flyby mission will play a key role in the later lander mission, as it will use its cameras to scout out plumes or cracks where material from Europa’s subterranean might ooze out. The lander will later visit these locations in order to take samples. Understanding Europa’s surface and subsurface will help researchers plan for future lander missions to the moon.

Our first strong evidence for a subterranean ocean on Europa came from NASA’s Galileo mission, which explored Jupiter and its moons in the late 1990s. But samples have never been collected from the ocean itself, which is thought to be buried beneath 19 to 27 kilometres of ice. The ocean, comprised of liquid water and an unknown amount of salt, is an estimated 100km deep.

In this new report, the SDT worked with NASA engineers to design a probe that would be capable of drilling about four inches into Europa’s icy crust to collect samples that could be analysed on the spacecraft for signs of life. If the lander is successful, a future mission to Europa could drill even further, maybe even reaching the subterranean ocean.

“I think it’s a great design,” astronomer and SDT member Jonathan Lunine told Gizmodo. “I was sceptical that we could in fact design a payload with a reasonable technological maturity and relative simplicity. Thanks to the engineers, a very practical solution was found and the payload we put together is not overly ambitious. The bottom line is I became much more of a believer that this is a mission that can be done in a time frame I’d be interested, in the next 20 years or so.”

In addition to a drill or cutter to extract samples, the team recommends that the lander include a camera system to see what’s going on outside, instruments for analysing the chemistry of Europa’s icy crust, and something to monitor geologic activity, like a geophone.

“The important thing to remember is that this is intended to be a ‘bug hunt,’ this is designed to land in a place where based on the Europa flyby mission, there would be deposits from the ocean, organic materials, that sort of thing,” Lunine said. “So the intent is to use instruments that can detect the signs of life on those samples.” The team is especially interested in finding biosignatures — isotopes or molecules that suggest past or present life.

There are a few reasons why scientists have long been keen to hunt for life on Europa.

“Europa provisionally is a great place to go,” Lunine said. “It has a very large amount of rocks, it’s got a lot of heat [at its core], so at the base of the oceans there are undoubtedly hydrothermal systems. Everything we know about it makes this a good [place] to look for life.”

Doug Vakoch, president of METI International, which focuses on seeking out radio signals from more advanced extraterrestrial life, agrees that Europa is a great place to look, but feels that scientists probably won’t get many answers until they can extract samples straight from the ocean.

“To have the best chance of finding life on Europa, we’d love to be able to drill beneath the icy crust,” Vakoch told Gizmodo. “That won’t happen with the first lander that NASA is now discussing, which would dig down only four inches.”

That said, Vakoch is still very supportive of the 2031 mission and what it could find.

“The top priority of this lander mission will be to search for evidence of life on Europa,” he said. “But even if that main goal isn’t met, we will learn a great deal about the potential habitability of this icy moon, which will be essential for future, even more ambitious missions.”

Both Vakoch and Lunine noted the similarities between Europa and Saturn’s icy moon Enceladus. Enceladus also has a subterranean ocean beneath its crust, but unlike the Jovian moon, its south pole features geysers that constantly spew ocean water out into space — offering free samples, so to speak. Cassini discovered these geysers in 2005, and has since made several flybys through Enceladus’ south polar plume.

There are rumours that NASA is considering a mission to search for life on Enceladus, which could launch as early as 2025. With all these missions occurring over the next few decades, our chances of finding beyond outside Earth are looking better than ever.

“Where do we have a better chance of finding life — Europa or Enceladus?” Vakoch said. “At this point, it’s a tossup. Both deserve exploration, and I’d hate to have to choose between them. If we really want to understand the prospects for life arising in subsurface oceans, some day we need to go to both.”

[NASA]