In 2006, then-New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg issued an executive order establishing the Office of Special Enforcement, a citywide agency responsible for enforcing “quality of life” regulations — a nebulous, ideologically charged concept that refers to anything from music venues with too many noise complaints to nightclubs that facilitate prostitution to decrepit structures that pose a fire hazard.

Illustration: Jim Cooke, Photo: Stephan Guarch, Shutterstock

That office expanded the work of a 40-year-old agency, the Office of Midtown Enforcement, that was essential in making Midtown and Times Square the shiny commercial hubs they are today, and created the paradigm for how city agencies “address issues and combat adverse conditions…that threaten public safety, community livability and property values and can lead to serious crime,” Bloomberg’s order read. That effort “should be continued and implemented on a Citywide basis to ensure that more communities in the City can reap the benefits of this approach.”

To do that, New York City enlisted the CIA-backed data analysis firm Palantir Technologies. In December, 2011, the city granted Palantir the first of at least five contracts, ultimately amounting to more than $US2.5 ($3) million, according to a review of public records obtained by Gizmodo. Palantir’s software has since become a centrepiece of New York’s mission to improve “community livability and property values” — that is to say, quality of life.

When Bill de Blasio took office in 2014, he doubled down, and paid Palantir $US907,413 ($1,194,712) for 24 “Gotham” server cores and licenses for the Department of Finance. Later that same year, the City paid $US20 ($26),000 ($26,332) to provide 10 inspectors from the Office of Special Enforcement (OSE) with Palantir’s mobile technology, connecting them to everything the city knows about every place within it. The tech has been used, among other applications, to crack down on illegal Airbnb rentals. “Thirty per cent more work with the same exact staff,” Elan Parra, the office’s acting director, told WNYC in 2015. “I guess maybe you could call it Moneyball for quality of life violations.”

Co-founded in 2004 by Peter Thiel and Alex Karp, Palantir’s inner workings remain shrouded in secrecy. But given what we do know, the service Palantir provides to clients appears simple: Entities like New York City (or Coca-Cola, or BP, or the US Marines) draw upon and produce an unimaginable amount of data every day. Palantir’s platform, in the company’s own words, “enables organisations to integrate disparate data sets and conduct rich, multifaceted analysis across the entire range of data.” It’s basically a high-powered version of Excel, rendering an incomprehensible amount of information legible, parsable, and ripe for analysis.

Valued publicly at $US20 ($26) billion (and privately at just under $US13 ($17) billion), Palantir reportedly collected only $US420 ($553) million in cash from the $US1 ($1).7 ($2) billion in “bookings” that it had claimed last year. A recent BuzzFeed News investigation revealed that many of the company’s most consistent clients are entities that cannot afford to pay its high fees — which can exceed $US1 ($1) million per month — including a slew of federal agencies that, since 2007, have paid the company about $US120 ($158) million.

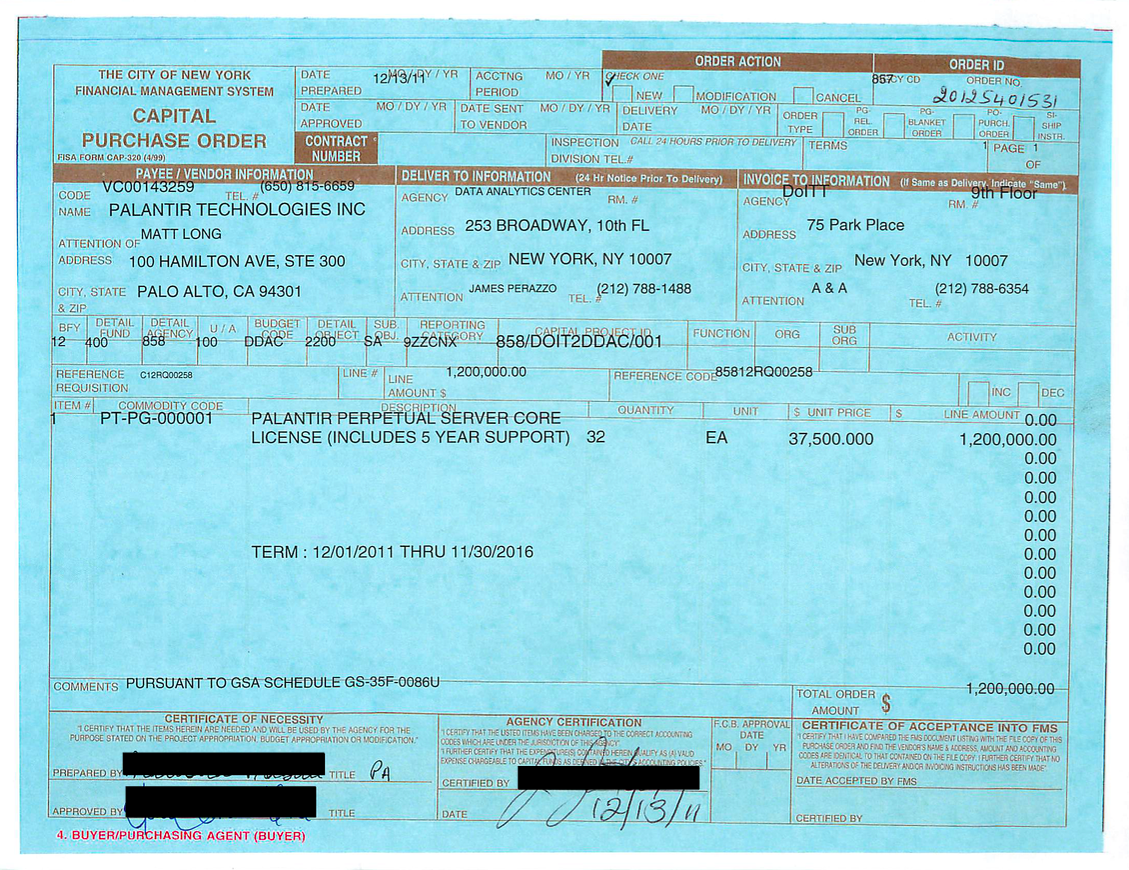

In its first purchase order to Palantir, New York City’s Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications (DOITT) paid $US1 ($1).2 million for 32 perpetual server core licenses, at $US37,500 ($49,373) each. (A “perpetual server core licence” means the city is licensed to use the Palantir software in perpetuity.) The licenses purchased under that contract, according to a document provided by the Department of Contract Services, were to be used by the Financial Intelligence Center, part of a Bloomberg initiative begun in 2011 to prosecute mortgage fraud.

Just a few months later, in May 2012, Palantir submitted a statement of work and a quote for a six-month pilot program with the Financial Intelligence Center and the Department of Finance’s Audit Division. The program would identify businesses and individuals avoiding or manipulating their taxes: “Palantir engineers will integrate relevant data sets and perform search, analysis, and other investigation activities.”

The deal went through in April 2013. That same month, Bloomberg created the Mayor’s Office of Data Analytics (MODA) by executive order. In June, the city paid $US236,906 ($311,914) for eight more Palantir “Cloud” licenses, with six months of support from the company’s technicians.

In December 2013, MODA issued its first annual report, lauding the Department of Finance’s use of Palantir, which enabled it “to better understand tax fraud in NYC.” The New York City Sheriff’s Office — a division of the Department of Finance — was using the technology to track illegal cigarette importation rings and “developing their own in-house intelligence team,” chief analytics officer Michael Flowers wrote. The report also revealed a pilot project in which MODA and OSE, using Palantir, “developed a tablet application that allows inspectors in the field to easily see everything that the City knows about a given location.”

NYC’s first purchase order to Palantir Technologies, for 32 “perpetual server core licenses”

Palantir described what the mobile program would look like in a September 2013 statement of work. “Palantir Mobile takes the capabilities of the Palantir Platform out of the enterprise and into the field, where mobile users can collect information in real time and relay it back to the Mayor’s Office (headquarters) for deeper analysis,” the document reads. In so doing, inspectors from the Office of Special Enforcement leverage “information from data sources across the city to hold building owners and establishments responsible for the upkeep and maintenance of the City’s quality of life.”

That information is maintained by something called “DataBridge,” a repository of data from 50 sources belonging to “roughly 20 agencies and external organisations.” There are nine datasets — updated nightly — that are integrated and managed using Palantir, a mayoral spokesperson told Gizmodo: “This is how we regulate and maintain oversight for all access and privacy issues.” The City Hall official discussed the city’s use of the data-mining technology on background, and declined to provide the full list of data sources or describe what is contained in the datasets.

All city agencies have access to DataBridge, but protocols regulate their access. “If they are requesting use of data that they are not providing themselves, they have to get specific permission to use specific data within Databridge, and will not be able to access anything beyond that,” the spokesperson wrote in an email. “Any data shared with Databridge has a designated point person or agency who needs to give explicit permission before that data is used, often requiring in-depth scrutiny of that use before permission is granted.” The mayoral spokesperson could not clarify how this reconciled with the “tablet application that allows inspectors in the field to easily see everything that the City knows about a given location,” and did not provide an answer in multiple subsequent queries. Palantir also did not return multiple requests for comment.

A DataBridge demo on Palantir’s YouTube channel shows how the technology can be used to better understand which buildings are more vulnerable to fires in the winter. But consolidating “everything that the City knows about a given location” into one place also raises questions about privacy and civil liberties — questions Palantir has tried to preempt with a white paper posted on its website. The document outlines a variety of “access restrictions” that law enforcement agencies can choose from, and in 2014 the New York Times reported that Palantir’s safeguards include “audit trails” that third-party investigators can review. These safeguards and restrictions are not mandatory.

The NYPD — whose record on privacy and civil liberties includes extensive monitoring of Muslim communities without warrants or specific threats — also uses Palantir. (Richard Falkenrath, a former deputy commissioner of counterterrorism in the department, said so during a 2010 presentation at the company.) According to City Hall, however, “There are no members of the NYPD and no prosecutors utilising the Databridge system.” A records request from Gizmodo for the department’s contract with the company was rejected on the grounds that disclosure would constitute an unwarranted invasion of personal privacy and would reveal “non-routine techniques and procedures.” The department did not respond to subsequent requests for comment.

Palantir is named for the palantíri, from J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings series — seeing-stones that allow one to spy on others across great distances (and be spied upon, in turn). Thiel — who, incidentally, is bankrolling a number of lawsuits against Gawker Media, the former parent company of Gizmodo — invested $US40 ($53) million of his own money in the company, which he saw as providing a bulwark against privacy invasions. “It was a mission-oriented company,” he told Forbes in 2013. “I defined the problem as needing to reduce terrorism while preserving civil liberties.”

As Palantir expands beyond the world of law enforcement and national security, its impact on our civil liberties — and whether rigorous safeguards are enacted to prevent overreach — remains to be seen. As Jay Stanley, a senior policy analyst at the ACLU, pointed out last year, “Government security agencies and others using data for “‘risk assessment’ purposes are trying to decide who should be blacklisted, scrutinised, put under privacy-invading investigatory microscopes, or otherwise limited in their freedom and opportunity.”

A city agency, like New York’s Office of Special Enforcement, could hypothetically use Palantir’s technology for purposes that go far beyond its mandate. The agency purports to improve people’s quality of life, cracking down on building and fire code violations, for example, or identifying illegal hotels in the form of Airbnb hosts abusing the service. (Ironically, Thiel is also an investor in Airbnb.) Such investigations often lead to fines levied against property owners, and sometimes evictions.

But, as the New York Daily News and ProPublica reported earlier this year, the 1977 “nuisance abatement” law that was passed to empower the Office of Midtown Enforcement’s prosecution of sex-related businesses in Times Square has metastasized over the last three decades, amended to include everything from the employment of unlicensed security guards to selling synthetic marijuana and fake IDs. In 1995, NYPD commissioner Bill Bratton called nuisance abatement “the most powerful civil tool available” in Broken Windows policing: In the year prior, the police department had brought 214 nuisance abatement cases; in 2013, it brought 1,082 — more than three quarters of them in communities where the population is 80 per cent or more people of colour.

City Hall did not respond to Gizmodo’s queries asking for further clarification on how OSE actually uses Palantir, or what role Palantir has in regulating and maintaining any kind of oversight of how its technology is used. Palantir still manages the servers that host data generated and interpreted by the city, but it’s unclear what kind of safeguards there are preventing Palantir from looking at what all that information.

A nightmare scenario of an Office of Special Enforcement inspector going rogue, stalking a colleague or creditor or lover with Palantir’s mobile technology, is certainly conceivable. But the potential for that kind of outright abuse is less disturbing than the ways in which Palantir’s tech is already being used. The city’s embrace of Palantir, outside of law enforcement, has quietly ushered in an era of civil surveillance so ubiquitous as to be invisible.

“It seems like the trickling down of ‘Big Data’ approaches from prosecuting real, significant wrongdoing into the enforcement of petty rules and regulations,” Stanley told Gizmodo. “Maybe it’s just enabling better management, but it seems like there is real potential for selective enforcement. If the authorities have enough data about you, they can always find something you’ve done wrong.”