It’s a well-known fact that the cadavers of adult men were utilised in medical research and for educational purposes in the 18th and 19th centuries. However, a new anthropological study from the University of Cambridge offers fascinating details about another common, but poorly-documented, area of human medical history.

Image: University of Cambridge

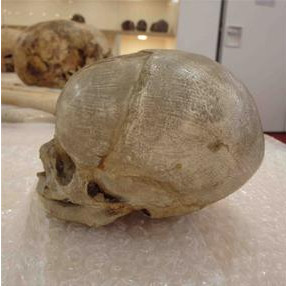

The paper, which was published in the Journal of Anatomy this week, traces the history of using infants and fetuses for dissection purposes, along with a catalogue of differences between how doctors dissected the smaller corpses versus the larger, more adult ones. The researchers examined the 54 bodies in the collection at the university and came away with some interesting observations.

Infants and fetuses were prized for their contributions to medical fields of study in the realms of growth, development and in diseases that could bring about early deaths. They were also treated differently than adult bodies, which usually underwent a craniotomy (the process of sawing open a skull to examine the brain). Instead, the skulls of infants and fetuses were typically kept intact, with just one in the school’s collection showing evidence of a craniotomy.

Doctors also seem to have been more delicate with these bodies, with soft tissues having been gently removed “in order to preserve as much of the bones of the head as possible,” the study wrote.

Image: University of Cambridge

“Foetal and infant bodies were clearly valued by anatomists, illustrated by the measures taken to preserve the remains intact and undamaged,” said Jenna Dittmar, a co-author on the study. “The skulls appear to have been intentionally spared to preserve them for teaching or display.”

These bodies made wide-ranging contributions in the medical field. Their size and stage in development made it possible for students to analyse the anatomy of the nervous and circulatory systems (the bodies were injected with coloured wax and displayed). They also helped students study the practices around surgery on young and small bodies, which aid medical professionals to this day.

Where Did The Bodies Come From?

The passing of the Murder Act in 1752 gave doctors the right to publicly dissect the bodies of executed criminals, the majority of whom were men. However, there was still a shortage of bodies available, so schools and researchers relied on “resurrectionists” to steal bodies from graveyards. Later, with the passing of the Anatomy Act of 1832, doctors were able to obtain bodies from the masters of workhouses and other institutions, who were able to donate unclaimed bodies of the poor.

Photo: University of Cambridge

So where did these small bodies come from? In conjunction with the rise in industrialisation and the spread of disease, the infant mortality rate was at an all-time high, especially for disenfranchised women who worked in unsanitary conditions or had children born out of wedlock. The New Poor Law in 1834, which ended parish relief for unmarried women, contributed to rising instances of infanticide, which also worked as a source of bodies. Anatomists would also purchase the bodies of stillborn infants from mothers and would pay by the inch. Fetuses were normally obtained from miscarriages.

“Poor and desperate women at the time of the industrial revolution could not only save the cost of a funeral by passing their child’s body to an anatomist, but also be paid as well,” said Piers Mitchell, a co-author on the study. “This money would help feed poor families, so the misfortune of one life lost could help their siblings to survive tough times.”

As morbid as it is to talk about the corpses of infants and fetuses, researchers say it’s important to recognise the contributions of the impoverished to the study of anatomy. “It’s a contribution that the poorest have made to medical research,” Elizabeth Hurren, a historian of medicine at the University of Leicester in England, told STAT. “We owe the poor… the most tremendous debt in the medical world.”

[STAT via University of Cambridge]