In books and movies, poisons are basically magic. It’s kind of a letdown to read about deliciously evil poisons and then realise they’re not nearly as potent in reality as they are in stories. Here are some myths about poison from pop culture — and the less impressive reality.

Quick Note: This entry contains spoilers for the book The Accursed, by Joyce Carol Oates. Skip it if you want to save your suspense.

Most Poisons are “Undetectable” Instead of Undetectable

There are still sources out there that call monkshood, or aconite, “undetectable.” Most of them are in museums, as monkshood was a favourite poison of the ancient Romans. It was the poison notable for dispatching the historical Claudius of I, Claudius fame. And that’s a relatively modern version of its use. This poison’s reputation goes back to Medea, who used it to try to poison Theseus. Since then it’s made appearances as a murder weapon in the medieval mystery series The Cadfael Chronicles and in the modern tv series Dexter. It’s been used in American Horror Story and James Joyce’s Ulysses.

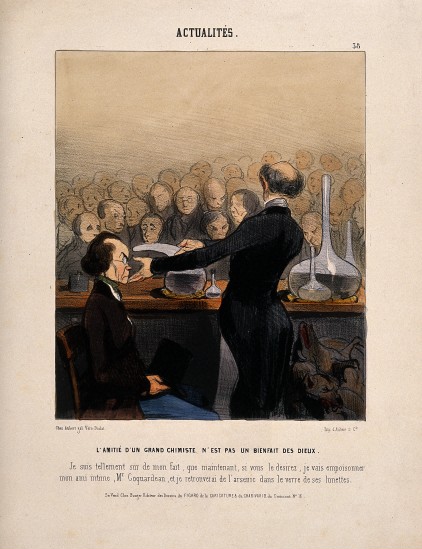

But the truth is, it’s been detectable for at least two hundred years. During the Victorian era, doctors began using a bit of monkshood for head colds. As soon as something is widely prescribed as a medicine, doctors become pretty well acquainted with the symptoms and toxicology of an overdose. Monkshood poisoning became so familiar that the Victorian public laughed at a hapless killer who read only the classics (they don’t make murderers like they used to) and so still believed monkshood was “undetectable aconite.”

Very few poisons are really undetectable. The best people can do is commit murder with a poison that’s relatively rare. In one of my favourite books as a young adult, White Oleander, a ruthless poet murders her ex-lover by dissolving the poison from a white oleander plant into DMSO and painting the mixture on his doorknobs. The DMSO allowed the poison to absorb into his skin. This is a bit more plausible than monkshood murder plots. It seems that in the 1980s, a man was poisoned with white oleander and foul play wasn’t confirmed for three years. Oleander poisoning was so rare that the coroner’s office didn’t think to look for it. DMSO, however, is not quite the sly move that the book made it out to be.

Although DMSO, or dimethyl sulfoxide, allows medications to seep in through the skin, it works better with some chemicals than others. (The poet in the book would have had an easier time poisoning her lover with morphine, or with mercury, but what can one do when one has an artistic temperament?) DMSO is far from undetectable, however. The chemical has a strong garlicky smell and received a massive amount of publicity when a woman who used it to treat her cancer pain collapsed and died. A complicated series of reactions caused the dimethyl sulfoxide, which is pretty harmless, to transform into the nerve gas dimethyl sulfate. The gas took out several members of the hospital staff where the woman was admitted. DMSO has been something hospital staff both can check for and do check for ever since.

There is no chance of undetectability, just obscurity.

The Ones That are Ineffective

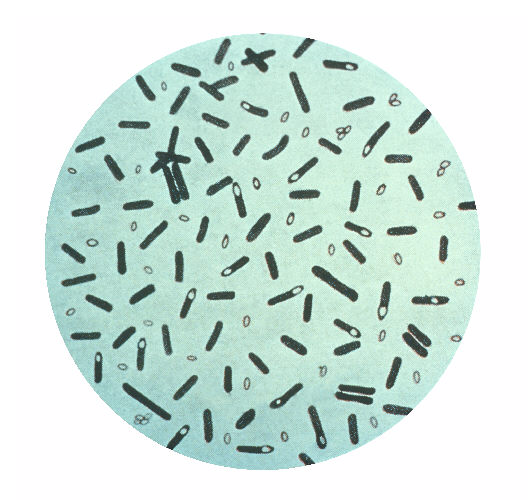

In the Sherlock tv series, a very young Moriarty kills his first victim by mixing botulinum toxin into his eczema cream. Moriarity times it just right so the toxin paralyzes the boy’s muscles when he gets into the pool during a swim meet. The victim drowns. While the killer gloated, he should have taken a bit of time off to give thanks for his incredible luck. An analysis of the fictional crime notes that the poison certainly could have made its way into the boy’s body, as eczema creates lesions on the skin. Timing would have been the problem. The toxin would take up to three days to cause paralysis, and there would be no way to ensure the paralysis happened during the brief time the boy was in the water. It could have happened any time during a span of two days.

Animal venom is also extremely ineffective ways of killing anyone. We’ve seen how reticent black widow spiders are to bite people in the first place. When they do bite, their bite is rarely fatal. The same goes for rattle snakes and lion fish and scorpions and anything else that James Bond was likely to face in movies made during the seventies. A lot of these animals deal out a mortality rate in single digits. Even truly deadly venomous animals make for a bad murder plan, as the ones that are likely to come into contact with humans have had antivenoms developed for them by now. And the ones for whom we have no remedy? Let’s just say that, if you have access to someone’s bedroom, it’s harder for law enforcement to trace a knife than an asp.

The Ones That (Don’t Really) Drive People Mad

I’m not saying that cruelly destroying a person’s mind in order to drive them to their death is fascinating and cool. All the rest of literature is saying that. And who am I to argue? The only problem is, in real life, tripping the loony switch isn’t as easy fiction makes it seem.

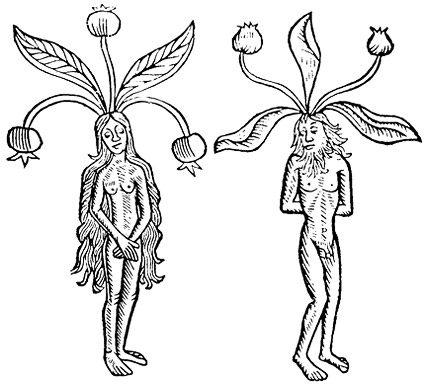

The most famous madness-inducer has to be the plant mentioned in the Sherlock Holmes story, “The Adventure of the Devil’s Foot.” The fumes from the burning root known as the devil’s foot cause horror, madness, and death within minutes. When Holmes burns it, as an experiment, he nearly kills both himself and his friend Watson. Unfortunately for fans of madness and death by candlelight, there doesn’t appear to be any such plant. The closest plant, linguistically, to the “devil’s foot” is the “devil’s shoestring,” but that’s a plant that was regularly ingested to get rid of intestinal parasites. It’s possible that Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was riffing on the concept of the mandrake root, which is said to cause insanity and death for those who ingest it or even pull it out of the ground. Mandrake does cause giddiness, restlessness, and distortion of vision when it’s ingested. Too much mandrake can kill. But there’s nothing that will cause people to “go mad,” and certainly not within minutes.

Mercury is famous for turning people into lunatics – in fiction. It’s the origin of the phrase “mad as a hatter,” and thus Alice in Wonderland’s Mad Hatter character. Hat makers from the 1700s to the early 1900s were regularly exposed to mercury. (Mercury was used to treat animals skins in the felt-making process.) They did have mental and cognitive problems as a result. The idea of using mercury to drive someone to violent madness did make its way into fiction. In truth, mercury poisoning gave hatters an uncontrollable tremor, and, while it did make them irritable, it also caused pathological shyness.

The most delicious fictional case of poisoning I’ve seen lately was in the Joyce Carol Oates novel, The Accursed – which features the devil coming to commit class warfare in Princeton at the turn of the last century. A young man, thinking he has seen a ghost carrying funeral lilies, takes a sample of crushed lilies found at the haunting site to his mentor. The professor takes the sample, intrigued, and slowly devolves until he becomes a mad fiend. Later the young man finds that the plants weren’t funeral lilies, but angel’s trumpet – a plant that causes slow, cumulative brain damage to those exposed to it. He was responsible for his dear mentor’s deterioration. Oh, that was good stuff. I ran to the internet to find out if the effects were real – and found that angel’s trumpet was the tree that grows in my neighbour’s yard. I’ve always loved it. Sniffed it every chance I got.

It was with some relief, then, that I found that angel’s trumpet was a mere hallucinogenic. It was not a wise hallucinogenic, however. People who have made tea from its leaves experience anything from a long, bad trip to hospitalisation. There has been one death reported. There’s also an alarming report of a teenager who drank the brew and amputated his own penis. No one who drank the tea or ate the leaves became violent towards others, and absolutely no one can have their brain eaten away by smelling the flowers. (Unless it’s already got me, and I’m hallucinating when I read the reports that it’s harmless.)

The Ones That are Just Disgusting

One of the reasons why people don’t get away with their fiendishly clever poisoning plots is poisoning is not nearly the neat event mystery novels make it out to be. Even doctors, with precisely-made medicines, often need to vary dosages and re-evaluate the time it takes for drugs to work effectively. They do this by asking people what they are feeling – because few drugs simply turn a person off like a light switch. People can feel a drugs effects and tell people around them what happened.

People also don’t quietly drop onto the settee and expire. They convulse and turn bright red when they’re suffering from cyanide poisoning. They turn into two-ended fountains with arsenic. Hemlock makes a person drool copiously before giving them tiny, horrible muscles twitches all over their body. All of these were symptoms that a lot of people recognised right away, because poisoners often used whatever was to hand. It was rarely a great mystery what caused a person to drop. A household that kills rats with cyanide isn’t going to be mystified by the same process occurring in a human being. The modern population may very well be less versed in what poison does, and the effects of common poisons, than past generations who worked with poisons every day.

Which is good. A nice murder mystery can, and perhaps should, be enjoyed without strict adherence to reality. I prefer a lady in a crinoline dropping primly onto the chaise longue after drinking her tea, or a cackling madman going after his family with a poker after sniffing something strange. In short, I prefer fake mystery to real pharmacology. And perhaps potential poisoners will read this entry, realise that it’s not so easy to get away with murder, and talk their problems out instead.

Via Analysis of a Toxic Death, Autopsy Limits Fail to Detect Rare Poisons, The Powers of Poison: The Science Behind Sherlock, The Devil’s Foot, Plants of Life, Plants of Death, The Poison Paradox, Angel’s Trumpet, Self-Amputation of Penis and Tongue.