Anterograde amnesia doesn’t allow people to make any new memories — and it’s a terrifying condition, when viewed from the outside. But what is it like from the inside? We’ll tell you a little about the daily life of the world’s most famous amnesia patient.

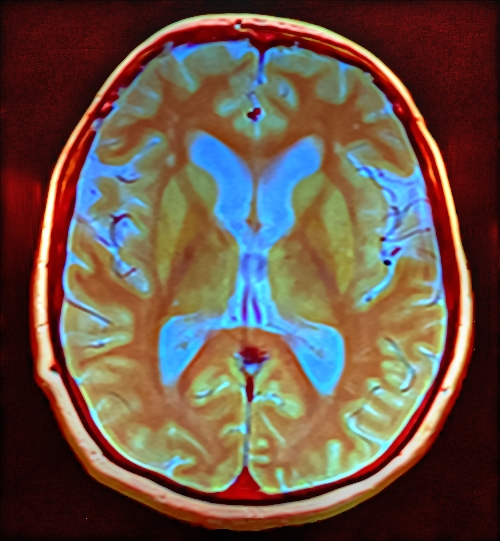

Top image: Maxwell GS on Flickr/CC by 2.0

The Patient

Henry Molaison was extremely famous for most of his life, but only under his initials. HM, everyone in the world was informed, had suffered from a progressive and dangerous form of epilepsy. HM had, at the age of twenty-seven, undergone a lobotomy in an attempt to cure his epilepsy. Afterwards, HM had ended up with anterograde amnesia. While his memories up until the operation were intact, he had no ability to make new memories.

The operation was performed in 1953. HM didn’t die — and so Henry Molaison couldn’t be named – until 2008. He never recovered from his surgical injury. He participated in research from nearly the moment people realised the nature of his injury until after his death, when his brain was studied by researchers. But how did he actually live? What was it like to go through days only thirty seconds at a time?

The Practical Side of Life With Amnesia

Injury on this scale is unimaginable for most of us. How could a person live without specialised care twenty-four hours a day? Although he did have caretakers, Molaison lived at home with his mother and father until he was in his late forties. Perfectly familiar as he was with his home, he was able to function there most of the time. There were some problems. Put food in front of him, and he would eat it. He’d finish nearly any meal. After he’d finished it, if he lingered too long at the table, he’d expect to eat again. Conversely, if he wasn’t given food he was rarely aware of hunger. Molaison didn’t have an idea of “meal times” and he didn’t start looking forward to lunch the way most of us do, so keeping him hydrated and fed could be a challenge.

Personal grooming was also a problem. When we feel grubby, it’s because we have an awareness of how long it’s been since we last cleaned ourselves. Molaison was willing to wash if he was told to, but otherwise wouldn’t be aware of how long he’d gone without brushing his teeth. He also needed notes to remind him to perform basic hygienic tasks, like lifting up the toilet seat.

Not every thought slipped away from him immediately. Molaison was aware that he had a “bad memory.” Over the years he came to know something of his condition, and find ways to work around it. At one point a researcher asked him to remember a sequence of numbers. She went out of the room and came back after twenty minutes. Expecting a blank stare, she asked him about the numbers. He correctly recited, “Five, eight, four,” and went on to explain.

“Five, eight, and four,” he said, “add up to seventeen. Divide by two and you have nine and eight. Remember eight. Then five. You’re left with five and four.” The mathematical process didn’t matter. All that mattered was Molaison rehashing the same sequence over and over in his head, before he could forget. It didn’t last, unless he was able to concentrate. After the researcher engaged him in brief conversation, he forgot he was even supposed to be thinking of numbers. Still, as long as he found a way to cycle through the same information, and wasn’t distracted, he could remember.

Molaison was not as helpless as his condition made him seem. He worked — albeit at a specialised work center. Notes and pictures were important parts of his work life. When he was asked to bring something back from a store, he needed a picture to remind him what it was. Still, he managed to do his job, and he realised that it was a job. When he eventually had to move into a care center, he could familiarise himself with the layout of his new home. He practiced in life what researchers were discovering through experiments — that we don’t always need conscious memory to learn.

The Emotional Side of Life With Amnesia

To those who hear about it, this kind of amnesia is one of the horrors of the medical world. Losing your pre-existing memories is sad — but provided we have the chance to make more memories, it’s not tragic. But losing the ability to make new memories seems like a form of torture — one which forces the victim to live for decades in a haze of confusion and fear.

But this wasn’t the case in reality. Molaison, according to the researchers who worked with him, was almost always cheerful and sanguine. He even made jokes, saying that if the point of life was to live and learn, “I’m living and they’re learning.” He was amused with certain quirks of his condition, and the strange pieces of information that would stick in his brain. For example, he knew the name “Yoko Ono,” but didn’t know the person it was attached to.

But even bright memories had their poignancy. It’s true that Molaison retained memories from when he was a young man, before the operation, but those memories had come untethered. He knew that he went roller skating once, but didn’t know when. He had memories of significant moments that happened at events, but didn’t remember the events themselves. To him, a fight between friends could have happened at his fifth birthday party or on the day he graduated from high school. There was no way to tell.

Dark emotional memories troubled him. At one point his mother was in the hospital with a minor problem and he was being driven to a care center. Molaison had visited his mother that morning and seen that she was well, but he was still restless and worried during the drive. When asked who packed his bag, he said, unprompted, “If there is something wrong with my mother, then it could have been my father.” He couldn’t quite remember the facts, but he knew something was wrong. Once the drive was over and he was in familiar surroundings, his sense of unease dissolved, as did the memory. After getting some sleep, the memory returned. He knew his mother was at the hospital. (Researchers have since found that sleep helps cement memories.)

As Molaison got older, his life came to resemble what we fear life with amnesia might be. His father died, and he couldn’t remember the event. His mother went into a nursing home, and eventually died as well. From day to day, he couldn’t remember whether his parents were alive or dead. His solution to this was to leave notes for himself — by his bed, or in his wallet. At random times, he came across these notes and would experience fresh waves of grief at the knowledge that he had lost his parents.

As he got older, he lost the ability to complete most of the tests he’d spent his life taking. He couldn’t remember the word “tennis racket,” although he knew an item on a card was “for tennis.” He became confused more often and for longer periods of time. Researchers who had worked with him for long periods of time would come to see him, and he was pleased to see them. Still, he was unable to recognise them as people who had shared his life. This was, perhaps, the saddest part of his condition. No matter how well he was cared for, he couldn’t recognise the people who cared for him. The researchers felt a deep connection to him, but it only went one way.

MRI Gif: BIGS-animation, Second MRI Image: © Nevit Dilmen

[Sources: Permanent Present Tense, Henry Molaison, The Man Who Forgot Everything.]