Earlier this month, a devastating wildfire swept through the Canadian city of Fort McMurray, prompting more than 88,000 residents to evacuate. As the out-of-control blaze continues to swell in size, a bigger picture is starting to emerge: major fires like this are the future, and we’d better get used to it.

Artwork by Sam Woolley

Since 1979, the duration of the fire season has increased by 20 per cent worldwide. The global land area affected has doubled, meaning regions that were once too wet to burn are going up in smoke. Worst of all, “megafires” that cover hundreds of thousands of acres, move at hypersonic speeds and swallow entire cities whole are now cropping up with alarming regularity. These raging infernos weren’t even on our radar until the late 1980s, but by the end of the 21st century, scientists say they could become the norm.

“The wildlands fire management environment has changed very profoundly,” Jennifer Jones, a spokesperson for the US Forest Service’s Fire and Aviation department, told Gizmodo. “We’re experiencing longer, more frequent, more costly, and more extreme fires. This is happening in many parts of the world.”

The time to adapt to the pyrotechnic future is now. That means ensuring wildfire response agencies have ample resources and personnel, fortifying fire-prone ecosystems, making full use of remote sensing technology, tackling megafires strategically and, in general, expecting the unexpected.

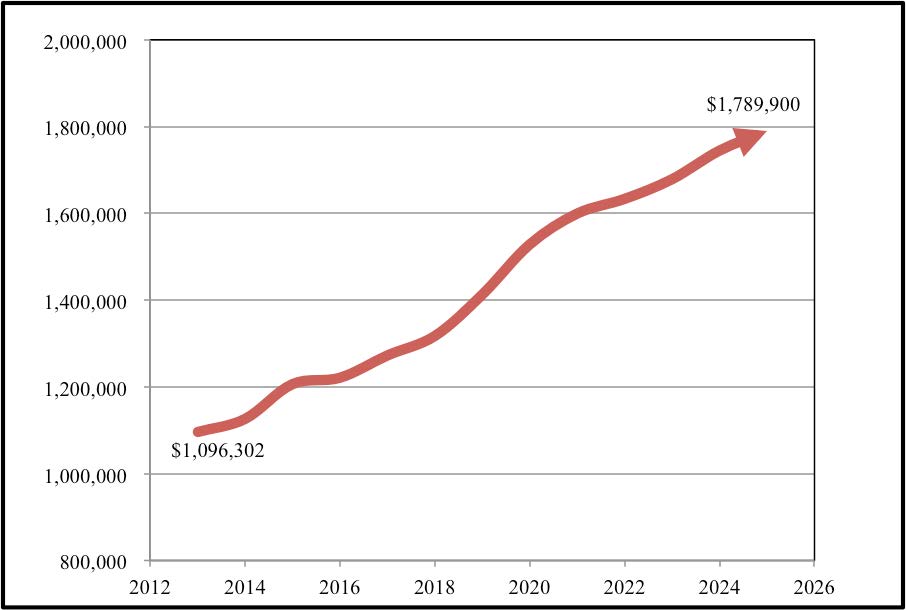

In the United States, wildfire suppression is paid for out of the same pot of money that funds all other Forest Service activities, from campground maintenance to conservation projects. This funding scheme made sense in a world where annual wildfire expenses were stable, but that’s no longer the world we live in. In 1998, 16 per cent of the US Forest Service’s budget went to wildfire suppression. In 2015, fire consumed more than half of the agency’s funds — a record $US1.7 billion ($2.3 billion). By 2025, the Forest Service estimates that wildfires will be depleting nearly 70 per cent of its budget each year.

Projected growth in the annual cost of wildfire suppression in the United States. Image: US Forest Service

More money spent on fires means less money for everything else the Forest Service does. The result? The agency has been forced to lay off thousands of employees and strip down many of its non fire-related programs.

The US National Forest Road System, a network of critical emergency access roads, has lost 46 per cent of its budget since 2001. The Deferred Maintenance Program, which “addresses serious public health and safety concerns” associated with ageing dams, sewers and other infrastructure, is almost entirely defunded. The Forest Service is even having trouble shoring up money for projects that directly impact the risk of future catastrophic fires, including controlled burns and thinning to reduce the buildup of hazardous fuels.

If this sounds completely arse-backwards to you, that’s because it is. And when you consider that a third of the cost of wildfire suppression in the United States goes to fighting the largest one to two per cent of fires — precisely the sort of fires that become more likely as we defund other Forest Service programs — it’s clear that something has to change.

“What we have proposed for the last few years is to fund really big, complex, costly fires not in our regular budget, but by tapping into disaster funds,” Jones said. “We’d like to see those big megafires treated as natural disasters.”

Australia, a country where large wildfires have always been a part of life, is also facing resource shortfalls as the fire season lengthens. When wildfires ignited across Tasmania’s World Heritage Forests for the first time in living memory this summer, the state fire service found itself outmatched. Tens of thousands of acres of pristine rainforest, including some of the oldest and rarest trees on Earth, went up in smoke.

On 7 February 2009, out of control bushfires raged through Victoria, claiming 173 lives in Australia’s largest wildfire disaster. Image: AP

“In the long term, our biggest problem is that there are not enough professional firefighters,” Paul Grey, a spokesperson for the Australian Firefighters Climate Alliance, told Gizmodo. “We’ve got studies predicting that fire season will increase 50 to 100 per cent by 2030. Right now, we’re overly reliant on volunteer brigades.”

Complicating the situation for Australia is the fact that there is no overarching national entity to deal with wildfire. As fire season gets worse, state fire agencies are increasingly crossing borders to offer services in other parts of the country. But each state’s training and equipment is somewhat different, and, as Grey put it, “a major critical emergency is not the ideal place to be learning a new system.”

Lesley Hughes, a councillor on Australia’s Climate Council, said that as fire season grows longer, it’s becoming harder for Australia, Canada and the United States to share water bombing aircraft, personnel and other resources. “Because the big fires in the northern hemisphere occur at a different time than the southern hemisphere, there’s a lot of sharing of equipment,” Hughes told Gizmodo. “As fire seasons continue to lengthen and become more severe, our ability to share will become limited.”

Preparing for the fiery future is more than a matter of throwing additional hoses at the flames. It means ensuring that our wildlands are fire-hardy, and that we’re doing everything in our power to catch big blazes early. “From a big picture, strategic standpoint, we are trying to make landscapes more resilient to wildfires,” Jones said.

To improve the resilience of wildlands, we need to minimise the accumulation of fire fuel. Unfortunately, a decades-long policy of stamping out all fires, including the low-intensity ones that flame out naturally, caused forests throughout the West to become thick and overgrown. The US Forest Service is now making up for this by conducing prescribed burning and thinning on approximately 2.5 million acres of land last year. It would like to be doing much more. “We’ve identified roughly 11 million acres at the wildland-urban interface that need to be treated,” Jones said.

A fire weather behaviour model for the High Park Fire, which burned 87,000 acres near Fort Collins, CO in 2012. Image: NCAR/UCAR

When it comes to nipping large fires in the bud, satellite technology is changing the game. Since 2001, the MODIS instruments aboard NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites have provided daily, global coverage of the land surface and atmosphere in visible and infrared portions of the spectrum, helping disaster management crews to spot remote fires early. More recently, the VIIRS satellite sensor has improved our spatial resolution on active fires. Coupled with wildfire-weather models, VIIRS data could, in the future, allow us to better predict where a large blaze will move in advance.

Very recently, satellites have also begun to monitor soil moisture conditions, filling an important gap in our understanding of fire conditions. “The majority of what is burning during a wildfire is on the ground,” Merritt Turetsky, a fire ecologist at the University of Guleph in Ontario, told Gizmodo. “It’s litter, moss, and peat. If we can track the moisture content of those fuels, we’ll have a better ability to predict when fire danger is high.”

But where humanity’s fleet of Earth-monitoring satellites shines most is during really big fires. Today, when there’s an event like the Fort McMurray fire, the disaster response community can put out a request to the International Charter Space and Major Disasters, mobilising satellites all over the world to collect round-the-clock information on the blaze. “There is a tremendous use of Earth observation data when there’s a major incident like the Fort McMurray fire,” NASA’s Vince Ambrosia told Gizmodo. “It’s like the Red Cross — everybody donates data.”

Even with the most sophisticated models and fire-resilient landscapes, megafires are still going to come. When they do, disaster management teams often have little choice but to let them burn — and that in itself underlies an important strategic shift. “Catastrophic wildfires are virtually impossible to put out,” Grey said. “You’re really talking about mitigating collateral damage.”

Travis Fairweather, a wildfire information officer with the Alberta state government, agreed. “We have to pick our priorities — in this case, communities and infrastructure,” he told Gizmodo, in reference to the megafire that tore through Fort McMurray earlier in the month.

Image: Getty

Fuelled by unseasonably warm weather and dry conditions, the Alberta megafire has been growing for weeks, preventing the displaced residents of Fort McMurray from returning to their homes. As last check-in, the fire had consumed over 800,000 acres of land, an area roughly the size of Rhode Island. While Alberta has seen several bigger fires in the past, including a 2011 inferno that scorched 1.7 million acres, past megafires occurred in remote areas of the province. To see an out-of-control wildfire cut a path of destruction through a large community is without precedent. “This is sort of a once in a lifetime event,” Fairweather said.

Air crews are water-bombing fire fronts that pose the greatest risk to people and property, while ground teams are creating fire barriers by clearing strips of land down to the mineral soil. But mostly, fire responders are waiting for cooler temperatures and rain to put the flames out, after which they will venture into the charred rubble and extinguish any smouldering hotspots. The entire process could take months, and it’s likely to be the costliest natural disaster in Canada’s history.

In the United States, recent disasters such as the 2013 Yarnell Hill fire that claimed the lives of 19 firefighters have also highlighted the need for caution, patience and flexibility when tackling large and unpredictable blazes.

“It used to be the case that when a fire started, you either suppressed the whole thing, or you allowed it to play its natural role in the environment,” Jones said. “Once you set that strategy, it was your strategy for the duration. Now, you might take aggressive action on the side of the fire that’s impacting communities, but there may be another part that you let burn. And your strategy can change over time.”

As disaster management crews learn to deal with bigger and hotter blazes in fire-prone landscapes, scientists are warning of an even stranger threat: fires in ecosystems that never used to burn. The waterlogged peatlands that pepper the Canadian boreal forest, for instance, are now drying out and igniting for the first time in living memory.

“Peatlands were never considered fire prone ecosystems — they have often been thought to serve as fire breaks,” Turetsky said. “We don’t yet have the tools for detecting and managing these types of fires.”

A harrowing scene in Tasmania’s World Heritage Forests, some of which burned for the first time in memory this past summer. Image: Dan Broun

Fire is a natural part of the lifecycle of many ecosystems. But the changes we’ve seen in the past decade — more fires, hotter fires, larger fires, weirder fires — are not natural, and they are not going away. As more people settle at the edge of wildlands, as invasive species transform ecosystems, and as climate change promotes more exceptionally hot days, mild winters and dry summers, our planet is becoming a tinderbox.

The men and women fighting fire understand this. It’s on us to provide them the tools and resources they need to adapt.

“The effects of climate change are fairly obvious to us as firefighters,” Grey said. “When you’re used to seeing fire season last four months, and it starts stretching to eight months, it’s something that’s ever present in your mind. I guess the thing you start to realise is that there’s a cost of inaction.”