Remember when we told you that the Venus flytrap can actually count? That’s how this carnivorous plant knows the difference between the presence of prey in its trap and a false alarm. Now the same team of German scientists is back with insight into how the Venus flytrap turned the evolutionary tables to become predator instead of prey. They describe this work in a new paper in Genome Research.

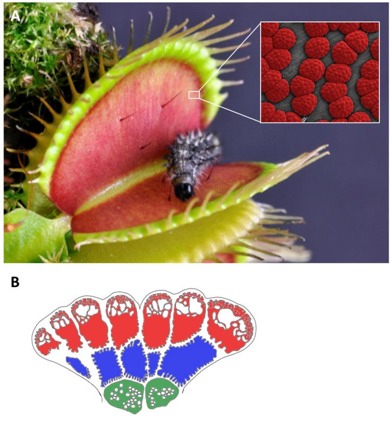

As previously reported, the Venus flytrap has a pleasing fruity scent, the better to attract unsuspecting insects to its deceptively welcoming leaves. Those leaves are lined with ultra-sensitive trigger hairs that sense when something touches them. When the pressure is sufficient to bend those hairs, the leaves snap shut, trapping the prey inside with the aid of long cilia that act like fingers, grabbing and holding the insect in place. And then the digestive process begins.

Image: Dirk Becker/Sonke Scherzer

Earlier this year, researchers at University of Wurzburg in Germany concluded that the Venus flytrap manages this feat by counting the number of times something touches its hair-lined leaves. Only after the fifth triggering stimulus would the flytrap begin excreting digestive enzymes.

They next planned to sequence the plant’s genome in hopes of uncovering further clues about traits specific to the flytrap’s penchant for meaty insects.

That’s where the new paper comes in. During their genetic analysis, the German team discovered that the same common plant defence systems that typically protect plants from being eaten by insects are used by Venus flytraps for insect feeding. Somewhere along its evolutionary timeline, the Venus flytrap adapted that defensive gene activation pattern into an offence, effectively switching from prey to predator.

For instance, when the researchers compared the Venus flytrap with the non-carnivorous thane cress, they found that both plants produce a defensive hormone called jasmonate. But the thane cress does so in response to injury — say, from the bite of a hungry insect — while the Venus flytrap does so when its sensory hairs detect potential prey. And the hormone serves different purposes for each: for the thale cress, it produces poisonous substances or make its leaves harder to digest, while for the flytrap, it kicks off the digestive process.

And counting isn’t the only means by which the Venus flytrap tells the difference between an inedible object and actual prey. Most insects have a chitin exoskeleton; the flytrap has a chitin receptor enabling it to “taste” an insect. The plant will produce even more digestive enzymes in response to the presence of chitin.

“Contact with chitin normally means danger for a plant — insects that will eat it,” co-author Rainer Hedrich said in a statement. This in turn triggers key defence mechanisms. “In the Venus flytrap, these defensive processes have been reprogrammed during evolution. The plant now uses them to eat insects.”

Top: Feed me, Seymour! The Venus flytrap is a smaller, but equally carnivorous, version of Audrey II.