Ludwig Boltzmann is best known as the Austrian physicist who wrote down the statistical formula for entropy, but if the physics thing hadn’t worked out, he would have made an excellent travel writer. The travelogue he composed of his 1905 trip to Berkeley, California, is chock-full of amusing anecdotes, keen observations, and local history of dubious accuracy. It’s pure joy to read.

Boltzmann was in his early 60s and already famous in physics circles when he accepted an invitation to teach at the University of California’s summer school in Berkeley, aimed at elementary and secondary schoolteachers. Perhaps the thought of travelling such a great distance was a bit daunting for a man who loved the comforts of home, but Boltzmann had an adventurous streak.

You can see it in his ecstatic description of sailing across the Atlantic aboard a majestic steam ship — along with his sly sense of humour. One minute he’s getting all teary-eyed and waxing poetic over the many brilliant changing colours of the ocean (“only on special days does the sea wear its most beautiful ultramarine dress”); the next, he’s taking perverse pleasure at the sunbathers yelping in alarm when a rogue ocean wave surged onto the ship’s deck.

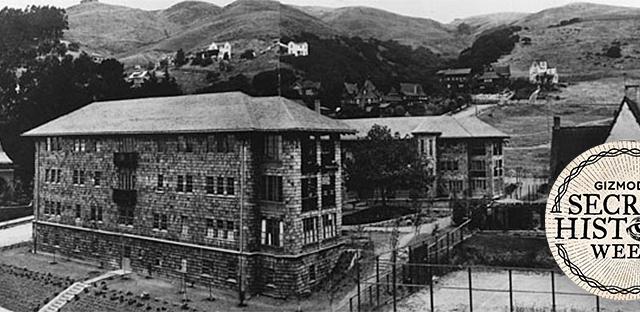

The Viennese physicist loved the hustle and bustle of New York, and seemed to thoroughly enjoy the two days he spent there. Next came a bumpy four-day train ride from New York to San Francisco, during which he struggled to order a lobster salad in English and admired the Great Salt Lake “covered with salt crystals like snow.” Then it was on to Berkeley, where he settled in at the Cloyne Court hotel — only to find that he would not be able to relax with a tipple before bed, because Berkeley at the time was a “dry” town by law.

Boltzmann was aghast. This was a man who loved his wine, and who readily admitted that his “memory for figures” got a bit fuzzy whenever he was “counting glasses of beer.” He never drank water from open-air bottles, because it upset his stomach, but given the lack of spirits, he was forced to do so, with predictably unpleasant results. In desperation, he appealed to a colleague as to where he could find a local wine merchant. The colleague looked startled and embarrassed that Boltzmann should bring up such an indelicate topic. But he guiltily admitted he knew of a supplier in Oakland.

A determined Boltzmann smuggled in cases of wine over the course of his stay and drank it secretly after meals. (On the train back to New York, he once again found himself battling temperance laws when the train passed through dry North Dakota; he bribed the conductors to bring him wine in the sly, not daring to try his luck with water again.) “Temperance is well on the way to creating a new kind of hypocrisy,” he observed, “of which there are already quite enough in the world.”

It must be said that Boltzmann was fairly high-maintenance as guests go. He suffered from insomnia and from stage fright before his lectures, and the Berkeley air aggravated his asthma. He also developed a nasty boil under his arm that had to be lanced at the local hospital. And by his own admission, Boltzmann had a “fastidious Viennese stomach.”

So it’s no wonder much of his travelogue lingers lovingly on descriptions of the food and drink he encountered on his trip. The fare available at Cloyne Court passed muster (barely), although he bemoaned the lack of printed menus and the monotonous sing=song tones of the “bespectacled waitresses.”

Alas, the culinary talents of his benefactor, Phoebe Apperson Hearst (whom he dubbed the “Alma Mater”), did not impress when the physicist paid a visit to her luxurious Livermore estate. At dinner, he waved away the blackberries and salted melon, but his hostess fixed him with such a deadly disapproving stare when the oatmeal course was served that he dared not refuse again. He choked it down, but pronounced it “an indescribable paste on which people might fatten geese in Vienna,” although he thought maybe even the geese would refuse to eat it. At least the other courses proved edible.

Boltzmann had nothing but praise for Mrs. Hearst’s exquisite taste in art, architecture, and fastidiously maintained grounds, taking particular pleasure in the Baroque music room — “I knew of no small concert hall in Vienna that could match it in beauty” — and her exquisite Steinway grand piano. He even let himself be persuaded to play a Schubert sonata after dinner, thrilling at the touch of the instrument’s keys.

For all his complaints, Boltzmann confessed he believed in America’s promise, “even though I saw it engaged in an occupation in which it does not excel: integrating and differentiating in a theoretical physics seminar.” (Meow! Ludwig couldn’t resist one last dig at his US colleagues.) And in the end, he quite warmed to Berkeley: “One can be as happy as a king with a quite simple meal, but California is Veuve Clicquot and oysters.” It’s just, you know, he was more of a beer-and-sausage man.

One would never guess, based on this wryly witty account, that Boltzmann had just one more year to live. Underneath that public facade, he was a deeply troubled man. Some have speculated that the physicist suffered from late-onset bipolar disorder, no doubt aggravated by the death of his son in 1889, his failing eyesight, and anxiety over how he would support his family if he went blind and became fully disabled. Certainly his Berkeley hosts had noted his oddly manic behaviour.

Still, his friends were relieved by the warm, relatively cheery tone of his Berkeley travelogue, figuring that all was, if not well, at least relatively stable. They were mistaken. Just a few months after returning to Vienna, Boltzmann briefly checked himself into a mental asylum, and although he soon returned to his academic post in Vienna, Ernest Mach, among others, cautioned that he should be under constant suicide watch.

Matters seemed to improve by September 1906, when Boltzmann went on holiday with his wife, Henriette, and youngest daughter, Elsa, to an idyllic Italian village near Trieste. But in reality, the depression was worse than ever. When his unsuspecting wife and daughter went out for a dip in the ocean, Boltzmann hanged himself in their hotel room. Poor Elsa found the body, and never spoke about the trauma for the rest of her life.

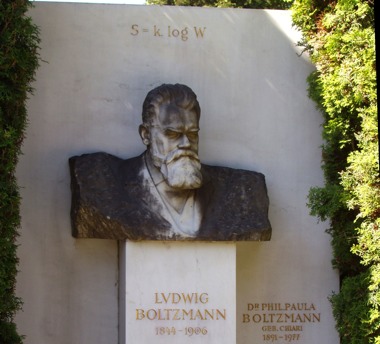

It’s a tragic coda for the man who wrote so lyrically about sailing on the ocean; who loved fireworks, Yellowstone Park, good beer and wine; who embraced atomism when few fellow physicists would, and gave us the equation for entropy. It’s inscribed on his tombstone, a poignant reminder that all things tend toward disorder and death — even the universe itself.

References:

Boltzmann, Ludwig. (1905) “A German professor’s journey into Eldorado,” English translation reprinted in Transport Theory and Statistical Physics 20(5&6): 499-523 (1991).

Cercignani, Carlo. Ludwig Boltzmann: The Man Who Trusted Atoms. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Images: Top: Berkeley’s Cloyne Court Hotel, Louis L. Stein, Jr. collection/Berkeley Heritage Society. Bottom: Boltzmann’s grave in Vienna, Austria. Credit: Daderot/Wikimedia.